It is a matter of public record that I adore living in France in general and Paris in particular. So much so, in fact, that when a French friend asked me the other day if there was anything I didn’t like about France, I had to think about it for a while.

I could have weighed in with the classic complaints about hostile store clerks and homicidal drivers. I have been tripped (yes, intentionally) by a saleswoman on my way out of a clothing store as punishment for failing to cede to her shamelessly dishonest hard sell, and I have been tailgated on the entrance ramp to an autoroute (think about that for a second). But I have noticed a lot of progress in those two areas in the 25 years I have lived here. These days, the customer is often right, even in Paris, and when I drive at the posted speed limit I only get tailgated about twice a day, instead of twice every 15 minutes.

I could have complained about the glaringly imperfect justice system, with its non-impartial judges and police who think they’re above the law. I could have groused about the onerous social charges or the absurdity of making people pay a tax for television ownership based on the premise that it replaces advertising on the national channels, which of course until recently broadcast advertising anyway. But, after much rumination, I finally came up with, two complaints – petty annoyances, really – concerning the French mentality.

Number one: The French are hampered by a misguided perception of social class.

A good illustration of this is an incident that occurred about a year ago. A few blocks down the street from where I live is a large building that used to house the main tax office for my arrondissement. I liked having it within easy walking distance; whenever I needed a form or had a check to deliver I could just drop by on my way to work. Then one day the fisc moved out and an extensive renovation project began in the building. A few weeks later I was walking by, wondering what the place was going to become, when I almost collided with a construction worker hauling a wheelbarrow full of debris out to the curb, so I asked him what the renovation was for, and he answered, “Don’t ask me – I’m just a worker.” His abrupt tone and manner implied that, as a worker, he couldn’t possibly know anything beyond the strict confines of his own job and that I was insulting him by assuming otherwise.

He was demonstrating a phenomenon that mystifies me: French people tend to classify themselves firmly and permanently, more or less from birth, as either an ouvrier (worker) or a patron (boss or manager). The reasons for this are both complex and debatable, but personally I blame the school system, which divides students into university track or non-university track at an age when most kids are still too young to know what they can or want to do. If you are of the ouvrier class, it’s understood that it is quite simply impossible for you ever to do anything so entrepreneurial as start a company or go freelance. You are foreordained to work for someone else for a fixed salary all your life. I know a great many intelligent, college-educated people who talk about les patrons as though they are a hostile species, a different breed of human that not only controls all the money but also has unlimited amounts of it. And, I have been told, many managers view their employees with a similar kind of distrust and disdain. As a product of the United States, where “anyone can grow up to be president,” I find this dismaying. But not quite as dismaying as…

Number two: The French pay a high price for teaching philosophy in secondary school.

On the face of it, this is a wholly admirable initiative: teaching children how to organize their thoughts and offering examples from the great philosophers. I doubt that many American high school seniors would be able to handle the essay questions that graduating 18-year-olds in France are given on the baccalauréat exam, such as “Can perception be taught?” or “Does art transform our consciousness of reality?” or “Can one feel desire without suffering?” (These are actual philo questions from the 2008 bac.) But all this intellectual exercise has an unfortunate side effect: the French schools are unleashing upon society thousands of people who have developed a taste for showing off their erudition by dominating conversations using the techniques they learned in philosophy class.

I don’t know how many times I have seen the pleasure drained from a dinner party by a second-class, and usually fifth-glass, philosopher who insists on expounding on some gratuitous thesis. The standard technique of these self-appointed doctors of philosophy is:

1) Choose a topic more or less at random from among the keywords presented in the conversation.

2) Make a grandiose and, most importantly, preposterous statement about that topic.

3) Pause to give everyone a chance to express amazement and perplexity.

4) Redefine the key word(s) in your statement to back up your assertion.

5) Look and act as if you’ve just won the Prix Goncourt.

The easiest and most common formula for step 2 is “A does not equal A.” In recent years I have politely endured dead-serious, lethally boring harangues on the following propositions:

The US dollar is not a unit of currency.

The British Crown Colony of Hong Kong (before the handover to China 1997) was not a colony.

Using electric cattle prods on prisoners is not torture.

American English is not a language.

Anthropology is a not a science.

A corollary to the latter supposition (sorry– fact!) was that the United States, a disproportionately frequent target of these rants, has more universities offering degrees in anthropology than the European countries, because the United States “has no history.” No one took the bait on that one, fortunately.

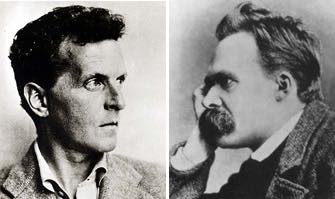

In my experience, the redefinition phase (number 4), usually takes 45 minutes, during which the son of a Nietzsche (virtually all of these would-be Wittgensteins are men) revels in the sound of his own voice. This, of course, is the soporific part. The only way to defeat it is to cut short the process at number 3.

WRONG

Dinner guest: I’m really interested in Japanese culture, especially the arts…

Self-appointed docteur de philosophie: The arts don’t have anything to do with culture.

Dinner guests: What? How so?

Dr Phil: Well, “culture” is a composite societal phenomenon consisting of … (20 minutes pass), whereas a work of “art,” whether in painting, music or literature, etc., is a … (15 minutes pass). Therefore, as you can see … (10 more minutes pass during which you can’t see because your brain has been sucked out of your skull).

RIGHT

Dinner guest: It’s fascinating how all these new communication media like cell phones and the Internet are changing the way people interact.

Self-appointed docteur de philosophie: The Internet is not a medium of communication.

You: Well, yes, of course. Everyone knows that.

Dr Phil: What? How so? (sound of air coming back into the room)

I suspect that the dilettante philosophical diatribe appeals to people who have a modicum of intelligence but few or no actual worthwhile ideas to offer in conversation and so rely on rhetoric to create, at least in their own minds, a semblance of interest. Interestingly, by the time I finished explaining all this to my friend who had asked me if there was anything I didn’t like about France, I had been ranting for 45 minutes. Hmmm…

Reader Sandra Fuenterosa writes: “The fatalism of the workers’ class, however, is not limited to France. It is basically European. What made the US what it was and created the American Dream of becoming whatever you wanted to become was purely and uniquely a phenomenon that occurred on American soil. But the irony is that that dream was actually brought into being by Americans’ European ancestors who became mortally tired of being the eternal grandsons and sons of the peasant or working class, with no hope of betterment. It was they who took the leap of faith across the Atlantic to a land where no one knew their history and could pigeonhole them; a land where they and their descendents could start afresh and become gentry themselves, like those who had kept them “in their place” in the old countries and whom they ultimately envied and wanted to emulate. That old system obtained all over Europe, in Italy, Germany, Scandinavia and all the other European countries that spurred some immigrants to seek fresh pastures.

Reader Reaction

Click here to respond to this article (your response may be published on this page and is subject to editing).

© 2009 Paris Update

Favorite