I could see the writing on the wall. And yet, though I was in darkness, with anguish and affliction all around me, I feared not. Because the writing was a question about speed limits projected on a screen in an auditorium full of driver’s license candidates, and I knew that the answer was “B.”

Yes, the moment of truth had come: after months of preparation, as recounted in Parts One, One-B and Two of this series, it was finally time for me to take the written and at-the-wheel tests to get my French driver’s license.

Passing these examinations requires four essential attributes:

1) A thorough understanding of France’s traffic laws,

2) An even more thorough understanding of the scheming, devious, downright perverse mentality of the people who write the tests on France’s traffic laws (as explained in Part One),

3) A modicum of skill and experience in operating a motor vehicle, and…

4) Money.

And not just a modicum of money. In fact, depending on their performance, applicants might end up needing a trunkload, truckload or buttload of money. A metric buttload.

In addition to the expense of driving school, which can cost several thousand euros, the official code (written) and conduite (road) exams cost upwards of €100 each just for the privilege of taking them. Which, for many (if not most) candidates, means for the privilege of failing them.

My experience with driving tests in the United States is that it’s possible to pass the written part with no more preparation than having or simulating common sense, and the road part simply by not breaking any laws or bones. But in France, relatively few people pass both exams on their first try.

So it was not without a frisson of anticipation that I signed up for this dual ordeal. Actually, I wasn’t too worried about the code test: I have never had any difficulty ingesting and regurgitating information. Or steak tartare, for that matter, but that’s a different kind of ordeal.

The written exam, which doesn’t involve any actual writing because it’s all computerized, consists of 40 questions, with a passing score of 35. That’s a 12.5 percent margin of error, which many French drivers apparently think also applies to speed limits, lane widths and the timing of red lights.

In any case… [Wait! Before I go on, I would like everyone to begin imagining, and if possible humming, the theme music from Star Wars. Thank you.]

I passed! On my first try! My score, for the benefit of my biographers and future editions of Trivial Pursuit, was 37.

Naturally, the three questions I missed were in the by-then-familiar category of “scheming, devious and downright perverse,” which I seem never to tire of mentioning.

I remember one of them quite clearly: the image showed an intersection at which the road ahead was a dead end, with cars parked along one side, and the crossroad was a one-way to the left. The question was “I have to turn left, true or false?”

I answered “false” because the sign for going straight said “dead end,” not “do not enter.” This was counted as wrong.

And that Dreyfus guy thought he got screwed! This was just plain unjust! The question did not specify, “I am passing through town.” It’s entirely possible that I could have some reason to go down that cul-de-sac.

I could live there or work there or know people who do. I could need to see a lawyer, chiropodist, loan shark or man about a dog there. I could be going to a quilting bee, orgy or microfilm drop site there. Other people are parked on that street, so why not me?

To this day, the memory arouses in me a resentment and indignation that is only partially assuaged by making anatomically correct gingerbread men with sprinkles spelling out “code test writer” and lowering them slowly into the food processor.

But I passed, and could finally move on to the final phase of the process: dreading the road test.

Although I may have a gift for swallowing and spewing information (and semi-digested raw beef), I have a whatever-the-opposite-of-gift-is (a foreclosure?) for physical performance under pressure. So I was not exactly looking forward to driving a car with an inspector inspecting my every move, waiting and hoping for me to do something wrong so he could fail me and stencil another skull on his dashboard.

Thus it was with a mixture of resignation and apprehension that I reported to my driving school early one cold, gray fall morning. There I joined two other candidates, a young man and a woman in their early 20s, and one of the instructors, who drove us out to the test site: the empty parking lot of a boarded-up strip mall in a sparsely populated suburb. The setting was as bleak as my mood and, as it turned out, my fellow students’ chances.

We were not alone. A steady stream of driving school cars arrived, and a vague, disorderly line slowly formed of about two dozen candidates, each of us clinging desperately to three things: hope, our instructors’ final advice and a self-addressed stamped envelope.

The reason for the latter is that, although the conduite inspectors make their decisions right away, the inspectees are notified whether or not they passed by post. And the reason, in turn, for this is (no kidding) that too many inspectors have been physically assaulted by applicants failing on their third, fourth or 12th attempts, which of course means time, effort and money out the tailpipe. This may be the only country in the world with a problem of road rage among people who can’t even drive yet.

The trial by tire is supposed to last 10 minutes to allow time for negotiating several kinds of intersections, a bit of freeway driving, some parallel parking and one technical question (example: “How do you turn on the fog lights?”). But if the candidate makes a disqualifying error, like running a stop sign or selling the test car, the inspector ends the session early to save time.

When it was our group’s turn, the two youngsters went first while I waited in the parking lot. They were back in about five minutes, implying that they had both failed.

As I found out afterward on the way back to Paris, the young man was on his fifth road test. Failing it meant that he had to take the written test again. If he did as well with the code questions as he did at the wheel, he would end up spending in excess of a thousand euros just on exam fees. And enough on postage to have his own commemorative stamp.

At last it was my turn. Frankly, I think the inspector threw me a bone. He was running late and had more potential assailants to assess, and he probably figured, “Here’s this middle-aged foreigner who’s already been driving for decades — I think I’ll just let him through and hope he doesn’t run over anyone I know.” This is also more or less how I got French residency (as I recounted last fall).

I drove for about seven minutes tops, was never asked to parallel park (thank dieu because I can’t do it without five tries or a cargo helicopter to lift me into place), and we skipped the tech question. Which was also deity-praiseworthy, because I still don’t have the smoggiest idea how to turn on fog lights.

But… [Is everyone still humming?] I passed! I got my notice in the mail the next day! Three weeks later I had my license!

And here, at last, comes the beautiful (i.e., French) part: I never have to renew it. In France, driver’s licenses are valid till death do you park.

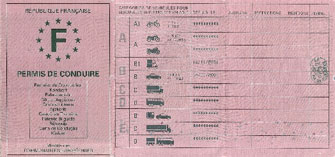

And after the beautiful comes the bizarre (but still French) part: this life-long permission to terrorize pedestrians and tailgate firetrucks is a flimsy piece of single-ply cardboard, folded into three sections, only one of which is laminated:

It’s also so big that there’s no way to keep it from getting worn and torn in any wallet or pocket. Perhaps the material acts as a built-in expiration date: by the time your license is all frazzled, frayed and faded, presumably your arteries, nerves and eyesight are too, and it’s time to stop driving.

But I’ve got it. It’s mine until I downshift for that final exit, legally authorizing me to ply the highways, byways and driveways (and dead ends!) of France. There’s only one problem: I can’t stop humming the Star Wars theme.

Next week in “The Long Gear-Grinding Road, Part Four,” I gleefully and legally take to the open road. And immediately get lost.

Reader Barney Kirchhoff writes: “Congratulations, David. Now go out and mow down some of those cyclists on unlit bicycles who speed through red lights and ignore all traffic rules and regulations. I guess your license also doesn’t give you the right to go after all those scooter maniacs and motorcyclists who roar up and down the sidewalks. Too bad, since the police apparently are too busy to devote a few hours occasionally to catching and fining these miscreants. A few stiff fines would teach a lot of them better manners. Witness what a little enforcement did to encourage a few (although not enough) dog owners to pick up their darling pets’ leavings.”

David Jaggard replies: “Mowing them down is indeed a nice thought, but if I try to cut anyone down to size, it’s usually in print. In fact, I already discussed your pedal- and petrol-powered peeves in a column a couple of years ago.”

Reader Ayn Lever writes: “I always look forward to your column – funny, pithy, dead-on takes on the dear French and their peculiar ways. I was especially amused (to put it mildly, more like peeing-in-my-pants laughing!) to read your three-part series on learning to drive (yeah, right) in France, as I have just been down that road, literally, myself and received that pink ‘flimsy piece of single-ply cardboard’ today! It’s all definitely some kind of French rite of passage (taking the Bac probably falls into that category, too) and so maybe it makes us a little more French (and broke!) to have gone through it all… Thanks for your column!”

© 2013 Paris Update

FavoriteAn album of David Jaggard’s comic compositions is now available for streaming on Spotify and Apple Music, for purchase (whole or track by track) on iTunes and Amazon, and on every other music downloading service in the known universe, under the title “Totally Unrelated.”

Note to readers: David Jaggard’s e-book Quorum of One: Satire 1998-2011 is available from Amazon as well as iTunes, iBookstore, Nook, Reader Store, Kobo, Copia and many other distributors.