|

|

Torsten Kerl as Siegfried and Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke as a campy Mime. Photo: Charles Duprat / Opéra National de Paris |

Two operas currently being performed in Paris, although written only 50 years apart, could hardly be more different from each other. While Richard Wagner’s Siegfried (the third of his four-opera Ring cycle) slowly evolves over the course of five hours, the action of Leoš Janáček’s tautly intense Káťa Kabanová is over in more or less the time it takes Brünnhilde to wake up! But what glorious music in each work, stunningly performed in both productions.

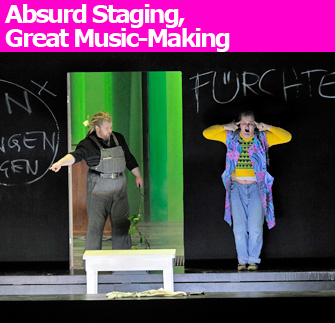

More on the music-making later. First, another, less felicitous, similarity between the two productions needs comment: the intrusive presence of the directors: Günter Krämer in the Wagner and Christoph Marthaler in the Janáček. To be fair to Krämer, he comes up with some striking visual imagery in Siegfried, most effectively in his use of groups of actors (depicting the inner workings of the forge furnace in Act I, machine-gun-wielding naked figures in the forest scene of Act II and fallen heroes in the final act), but his choices are sometimes perverse if not objectionable. The portrayal of the dwarf Mime has long been a subject of controversy: early productions of the opera depicted him as a stereotypical Jew, but, mercifully, such distasteful interpretations have long since been abandoned. What is Krämer’s solution? He makes Mime into a campy queen dressed in ill-fitting multicolored clothes and has him mincing around the stage. Nothing like replacing one offensive stereotype with another offensive stereotype. On a theatrical level, it also undermines the beauty of the music. At the entrance of the Wanderer (who is the chief God Wotan in disguise), for example, his noble vocal lines are completely undercut by Mime prancing around, holding his nose and spraying room deodorizer. And the magic of the forest scene is destroyed by having the wood dove acted by a bespectacled woman in army fatigues.

But while Krämer still maintains a certain vision and narrative energy, Marthaler displays little interest in giving any consistency to his production of Kát’a, deemed to be the greatest success of the ghastly years that Gérard Mortier was general director of the Opéra National de Paris. By setting it in the courtyard of a drab Soviet tenement block, he brings out all the bleakness and none of the beauty of the piece. Yet, at every moment when he could usefully exploit the location, he ignores its theatrical possibilities. The mother-in-law from hell, the

|

|

Jane Henschel as the Kabanicha, Angela Denoke as Katia and Andrea Hill as Varvara. Photo: Christian Leiber / Opéra National de Paris |

Kabanicha, for instance, is played for laughs, while the storm scene is transformed into a parody of Singing in the Rain. Throughout the opera, a blind man wanders around the stage for no obvious reason other than to snigger menacingly and knock over a few objects before the final act. In trying to find some meaning in this figure, I thought he might be transformed into the humming passerby who ignores Kát’a in the final scene, but no such luck! Another missed opportunity: the looming apartment windows overlooking the set could have been filled with curious onlookers in the devastating final moment of the opera when the Kabanicha thanks everyone for helping, but Marthaler chooses this moment to clear the windows of spectators.

Thank heavens (or thank Valhalla), then, for the music-making. I had my doubts whether the young director of the Opéra National de Paris, Philippe Jordan, would be up to the stern challenge of the Ring, but, if this Siegfried is anything to go by, he has the intelligence and energy to maintain the momentum of the music and drama throughout the cycle. The role of Siegfried (memorably described by Anna Russell: “He’s very young, and he’s very handsome, and he’s very brave, and he’s very stupid”) is notoriously difficult to sing, but in Torsten Kerl the operatic world has found a very good and potentially great heldentenor: his performance was as subtle as it was strong. Juha Uusitalo is an imposing and vocally pure Wanderer, and Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke makes up for the absurd campery with a very well-sung performance of Mime. Katarina Dalayman’s Brünnhilde crowned an impressive evening with a suitably ardent interpretation of the sublime love music sung with Siegfried as he wakes her from her long slumber amid the flames.

It was an excellent decision to engage the Czech Thomas Netopil to conduct Kát’a, as his familiarity with the very particular rhythmic idiom of Janáček’s music elicited a superb performance from the orchestra. And German soprano Angela Denoke is a truly great Kát’a, affecting and thrilling at all times, in spite of the absurdities of Marthaler’s staging. Impressive vocal support is given by Jane Henschel as the Kabanicha, Jorma Salvasti as the spineless lover Boris, Donald Kaasch as Kát’a’s (rather too elderly in this production) ineffectual husband Tichon, and Andrea Hill and Ales Briscein as Varvara and Kudriach respectively.

Siegfried: Opéra National de Paris: Place de la Bastille, 75012 Paris. Métro: Bastille. Tel.: 0 892 89 90 90 or + 33 (0)1 71 25 24 23 (from abroad). Remaining performances: March 15, 18, 22, 30 at 6pm, March 27 at 2pm. Tickets: €5-€180. www.operadeparis.fr

Káťa Kabanová: Opéra National de Paris: Palais Garnier, corner of Rue Scribe and Rue Auber, 75009 Paris. Tel.: 08 92 89 90 90 (+33 1 72 29 35 35 from abroad). Remaining performances: March 16, 21, 23, 29 and April 1, 5 at 7.30pm. Tickets: €10-€140. www.operadeparis.fr

Support Paris Update by ordering music and books from Paris Update’s Amazon store at no extra cost. Click on your preferred Amazon location: U.K., France, U.S.

Reader Reaction: Click here to respond to this article (your response may be published on this page and is subject to editing).

© 2010 Paris Update

Favorite