|

|

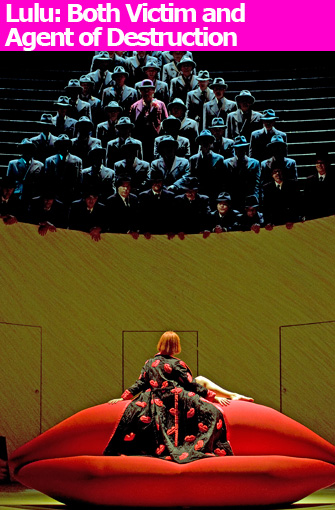

Men in fedoras watch Lulu’s every move from the shadows. © Opéra National de Paris/Ian Patrick |

Lulu, the figure inspired by two Franz Wedekind plays, seems to have fascinated writers, composers and filmmakers in the early part of the 20th century as much as the biblical figure of Salomé mesmerized writers, composers and artists in the latter years of the 19th century. Whereas Salome’s lust for John the Baptist appealed to the spirit of fin-de-siècle decadence, Lulu epitomized something more modern and complex. She is both victim and agent of destruction, both emprisoned by and liberated from capitalist society. It is therefore particularly fitting that the Bastille Opera House has been staging both Richard Strauss’s Salomé and Alban Berg’s Lulu this season.

Berg’s unfinished operatic adaptation (the third act was fully orchestrated by Friedrich Cerha and first performed in 1979, 45 years after Berg’s death) is an extraordinary work, combining a large cast and an astoundingly new musical language. Inevitably, the opera stands or falls on the singer chosen to play the mesmerizing role of Lulu. Unfortunately, in this production, although American soprano Laura Aikin has the technique to tackle the formidable vocal challenges of the part, she is completely lacking in stage presence or allure. On the opening night, she was not helped by the accurate but surprisingly lethargic playing of the usually superb Orchestra of the Opéra National de Paris. In the first act in particular, conductor Michael Schønwandt seemed intent on blunting the sharp edges of the music. Only in the final act, as Lulu moves towards her violent end, did the orchestral playing achieve any real intensity.

Willy Decker’s production, on the other hand, is a triumph. Although it has been doing the rounds for a number of years, it still packs a punch. The actions onstage are almost continuously watched from above by a sinister pack of men in fedoras assembled on black bleachers in the back of the stage, symbolizing the many male eyes that create, lust after, are seduced by and destroy Lulu. The moment that they all invade the stage in the final act and symbolically enact the stabbing of Lulu by Jack the Ripper is truly terrifying.

Another positive feature of this production is the supporting cast. I will single out two of them. Wolfgang Schöne has become indelibly associated with the role of the almost identically named Dr. Schön, the man who seems to have groomed Lulu from a young age and who constantly tries and fails to escape her. In the long history of classic operatic letter scenes (one only has to think of the Countess in The Marriage of Figaro or Tatiana in Eugene Onegin), the episode in Lulu where Lulu dictates a letter to Dr. Schön in which he calls off his engagement to a rather more socially acceptable fiancée is surely the most devastating in the operatic canon. Berg cast the singer performing Schön (who is murdered by Lulu) as Jack the Ripper as well, adding a grim sense of inevitability to the cycle of violence. After a rather anonymous start, Jennifer Larmore, as the lesbian Countess Geschwitz, the only person who seems to love Lulu unconditionally, comes into her own in the final act; the final words of love for the countess’s “angel” that finish the opera are gorgeously sung. Since the countess has just decided to study law so that she can fight for the rights of women, her murder in a squalid setting at the hands of Jack the Ripper seems all the more brutal and senseless.

Opéra National de Paris: Place de la Bastille, 75012 Paris. Métro: Bastille. Tel.: 0 892 89 90 90 or + 33 (0)1 71 25 24 23 (from abroad). Remaining performances: October 21, 24 and 28, November 2 and 5 at 7:30pm. Tickets: €5-€140. www.operadeparis.fr

Support Paris Update by ordering music and books from Paris Update’s Amazon store at no extra cost. Click on your preferred Amazon location: U.K., France, U.S.

Reader Reaction: Click here to respond to this article (your response may be published on this page and is subject to editing).

© 2011 Paris Update

Favorite