One of the main functions – and values – of science fiction is its ability to critique today’s society. Although a story may deal with vastly different cultures and be set in the future, an alien world or an alternate-history scenario, this distancing facilitates commentary on the present.

In Ray Bradbury’s short story “The Other Foot” (1951), for example, an African-American community has settled on Mars to escape injustice on Earth. When some Caucasian astronauts fleeing Earth, which is destroying itself with nuclear weapons, arrive on Mars, the original settlers initially want to institute a racially segregated system in retaliation for the mistreatment back home. Instead, they decide to show compassion and tolerance, things they had never experienced in America.

Similarly, Charles Beaumont’s “The Crooked Man” (1955) sets out a dystopia in which heterosexuality is strictly forbidden. When a man and woman meet furtively in a gay bar, they are arrested. These two powerful tales, published during the troubled period of McCarthyism and the Cold War, challenge readers to imagine themselves as part of a minority to which they may not belong.

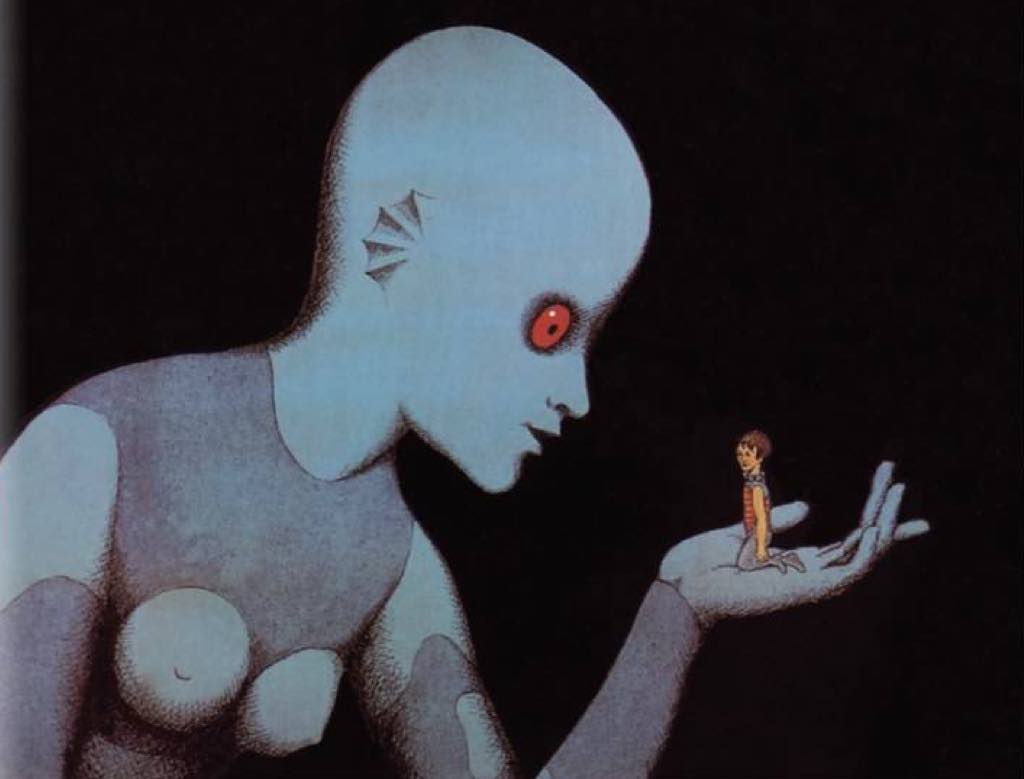

From France, René Laloux’s wondrously imaginative animated movie Fantastic Planet (La Planète Sauvage, 1973) is a parable of oppression in human history. On a planet called Ygam, the dominant race of highly advanced reptile-like humanoids with blue skin and red eyes, the Draags, keep human beings as pets. The humans are so tiny compared to their captors that they can fit into their hands. It transpires that the Draags had abducted humans from Earth at some point in the past, which explains why they are called Oms, a corruption of “hommes” (French for “men” or “humankind”).

The movie opens with a woman holding a baby being tormented by a group of Draag schoolchildren. At first, we see only the weapons being used to torture her, then her gargantuan murderers come into the picture. These young Draags are just having a bit of fun. When the woman is dead, one of the children callously remarks, “What a shame we can’t play with her anymore.”

That compelling opening dramatically reveals this world’s power structures. The baby survives and is taken by a schoolteacher, who finds him in the playground, as a pet for his daughter, Tiwa, who names him Terr (evoking “terre” or Earth). The boy grows up with a rebellious streak and surreptitiously uses Tiwa’s teaching aids (headphones that deliver a hypnotic podcast) to educate – and empower – himself.

We learn along with Terr, as the lessons also provide us with the history of the planet and the human diaspora. He runs off after freeing himself of a vicious stun collar and finds refuge with a tribe of wild Oms – a significant number of them live in the planet’s rural areas. When Terr discovers that the Draags are planning a wide-scale genocide of the free-roaming human “pests,” he coordinates mass attacks on the Draags and procures teaching aids to educate his fellow Oms. I won’t give away the ending, but it involves the planet’s satellite, the fantastic planet of the title.

The movie, which won the Grand Prix Special Jury Prize at the 1973 Cannes Film Festival, has a memorable soundtrack and is easily interpreted as a metaphor for the African slave trade. There is special poignancy in the themes of oppression and uprising given that the film was a French-Czech co-production: the Czech participants had recently experienced the brutal Soviet repression of the Prague Spring in 1968. The work retains its relevance, sadly, since we can always draw parallels with the racial conflicts that still plague our world.

Fantastic Planet is based on a 1957 novel by Stefan Wul, Les Oms en Série. Wul was the pen name of Pierre Pairault (1922-2003), a dental surgeon who got into sci-fi after his wife read a particularly bad sci-fi novel and concluded that her bookworm spouse could write a better one. He did and published an eye-watering 11 novels between 1956 and ’59 and a final one in 1977. Wul’s style is as poetically concise as it is imaginative, and his early novels have been highly influential.

Interestingly, Wul was unfamiliar with the dominant sci-fi tradition in English-language literature, so the common motifs of 1950s sci-fi are largely absent from his stories. His collected works were republished by the French press Bragelonne in four volumes in 2013 and ’14, and the graphic novels of Les Oms en Série appeared in 2012, with the first French collaboration of award-winning American comic-book artist Mike Hawthorne. All this from a dentist whose wife dared him to write good sci-fi!

This article is part of a series of essays on French science fiction by Prof. Paul Scott. The others can be read here, here, here, here and here.

Fantastic Planet can be streamed on Amazon and YouTube (starting at $2.99).

Favorite