In Comics in French: The European Bande Dessinée in Context (2010), Laurence Grove makes the case that the BD developed from Renaissance emblem books, giving the ninth art a long and noble pedigree. It could even be argued that the concept stretches back as far as cave paintings.

One of the most famous French-language BD artists is Hergé, whose Tintin albums have been translated into countless languages. Hergé was the pen name of Georges Rémi (1907-83), a Belgian who came up with his pseudonym by inverting his initials, Hergé being the phonetic transcription of “RG” in French.

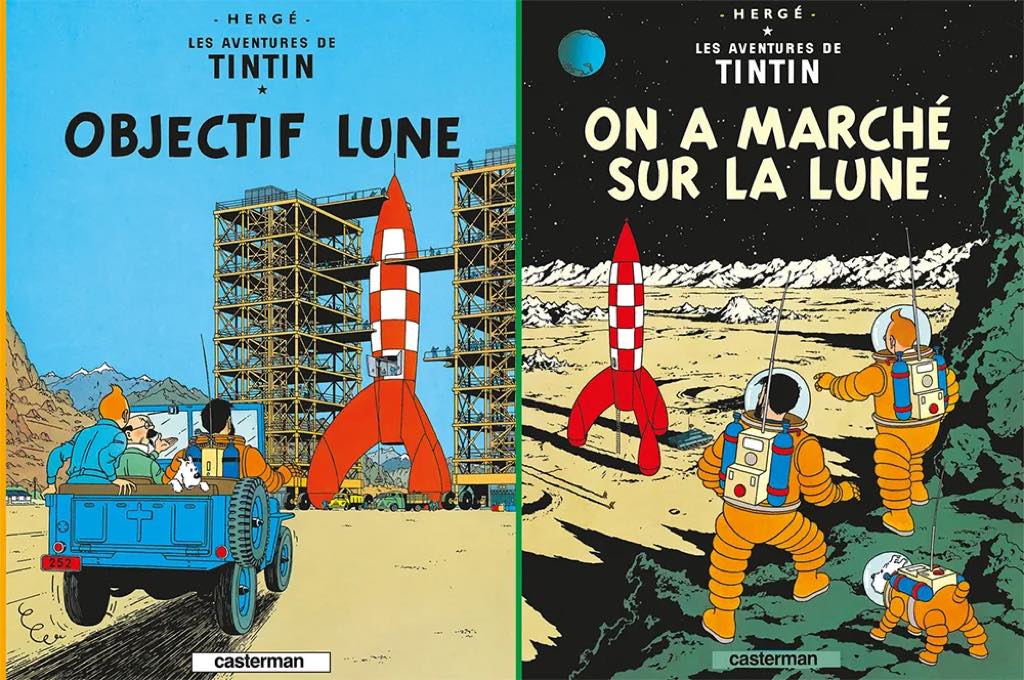

The Tintin albums might seem to be more suitable for a younger audience, but when Hergé ventured into the realm of science fiction in the only two-part Tintin adventure, Destination Moon (Objectif Lune, 1953) and Explorers on the Moon (On a Marché sur la Lune, 1954), he created a complex thriller that appeals to readers of all ages, and I strongly recommend reading or revisiting it. (It should be noted that some of the racial and gender stereotypes in the cartoonist’s work are troubling products of their time, but, to his credit, he did later rework many of these motifs and was conscious of how they had dated.)

The story arc is neatly divided into the preparations for a Moon expedition in the first volume and the return voyage in the second, and the artwork is among the most accomplished and influential of Hergé’s entire output. Some of the panels deserve to be framed as works of art. In teaching these two albums, I’ve often had sustained and lively discussions about some of the illustrations in the series.

The tale has the most scientific depth of Hergé’s narratives. He spent years obsessively immersed in meticulous research on the principles of rocket engineering and science. He even became so convinced about the imminent prospect of space travel that he fiercely resisted repeated efforts on the part of his publisher (Casterman) to change the title of the first part, We Walked on the Moon, which was thought to be too fanciful – the manned Moon landing occurred only 15 years later, in 1969. Hergé also strove for realism by eschewing drastic plot developments or any mention of extraterrestrials.

In the first album, Tintin, Captain Haddock and Snowy the intrepid terrier travel to the fictional country of Syldavia to assist Professor Calculus in a secret mission to build and launch a manned spacecraft. In this album, Calculus becomes more than the usual one-dimensional eccentric seen in other plots and is revealed as a man with weaknesses, ambitions and emotions.

In a nod to the wider context of the Cold War and anticipating the highly politicized space race that would begin shortly after the works’ publication, various attempts are made to harm both the professor and the project. The album ends with the launch of the rocket and all the astronauts losing consciousness.

The sequel covers the journey to and arrival on the Moon. Their return is endangered by some stowaway spies overpowering the crew. The traitor in their midst is unveiled as Frank Wolff, an Austrian mathematician and engineer who makes for an unassuming mole. In order to save the others, Wolff redeems his treachery by jettisoning himself into space, reserving the limited oxygen supply for the others. He leaves a poignant suicide note explaining his guilt about having been blackmailed into espionage. This serious and moving storyline signals that this is not simply a children’s comic book. And, along with its psychological and political subtext, the work is rich in literary and cinematic allusions to Jules Verne and Georges Méliès.

The two albums contain some visually stunning splash pages (a panel or box that takes up a full page), including the blueprint of the rocket, which can be compared, several pages later, with the constructed final product. Its familiar red and white pattern has become part of popular culture. The Belgian Comic Strip Center (also known as the Comic Arts Museum) in Brussels, well worth a visit, has a huge replica of the rocket in its lobby.

This article is part of a series of essays on French science fiction by Prof. Paul Scott. The others can be read here, here, here, here, here and here.

Favorite