It is always an intriguing exercise to try to guess which operatic works written in this or the last century will stand the test of time. In the French repertoire, an opera like Olivier Messiaen’s sprawling Saint François d’Assise (1983), with its requirement for an orchestra of 110 musicians and a 10-part, 150-voice choir, has perhaps inevitably not been staged very often. Two other 20th-century operas, however, seem to have lasted the course, and for very good reasons. The first, Claude Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande (1902), while drawing on Richard Wagner’s use of leitmotifs (memorably defined by the comedian Anna Russell as “signature tunes”) and through-composition, managed to create a very distinctive and new musical language. Here, I would like to discuss the second, Francis Poulenc’s Dialogues des Carmélites (1957), which makes a very unlikely masterpiece.

What chance of success could an opera – written by a newly converted Roman Catholic but openly gay man – containing no conventional love plot and consisting almost entirely of female singers possibly have?

As it happens, all these aspects combine magnificently to create a nuanced, profound and unsentimental meditation on faith, courage and death. Although the opera is placed within a conventional three-act structure, it is essentially made up of a series of encounters (the “dialogues” of the title), which give it a fragmentary, episodic effect. Some directors and conductors try to smooth over these edges, but to my mind, this jagged quality is essential to showing that the work is not a fluid hymn to piety but rather an urgent exploration of the contradictions and difficulties of existence, with or without faith.

Inspired by real events that occurred in the aftermath of the French Revolution, when nuns from the Carmelite order in the town of Compiègne were sent to the guillotine, Poulenc drew his material from a play by Georges Bernanos, which itself had started as an unsuccessful screenplay based on a novella by Gertrud von le Fort (whose name is uncannily similar to that of the heroine of the opera, Blanche de la Force).

At the beginning of the opera, Blanche chooses to flee her aristocratic home and join the Carmelite convent as a novice nun. Her motivations are unclear, perhaps even to herself, but the prioress, Madame de Croissy, who is mortally ill, insists that she must not use the convent as a refuge; she and her fellow nuns should instead see it as their mission to guard the order.

At the end of Act I, the scene of Madame de Croissy’s death, witnessed by Blanche, is truly horrifying because, far from expiring in a state of spiritual peace, she dies in agony, crying out that God has abandoned her. It is a masterstroke on the part of Poulenc to not only anticipate the very different deaths that will occur at the end of the opera but also to show the human frailties of these women of God.

I would thoroughly recommend watching the scintillating performance of this scene by the incomparable Karita Mattila in the 2019 New York Metropolitan Opera production if it were easily available, but Rosalind Plowright’s typically gritty (if visually murky) rendition can be watched online.

One very real danger of an opera set in a convent is that all the characters will become indistinguishable from each other under their identical wimples, but Poulenc succeeds brilliantly in drawing sharply delineated personalities. Blanche, headstrong, complicated and anguished, could not be more different from her fellow novice, the sunny-natured, seemingly unquestioning Constance, who turns out to have a more complicated response when faced with the reality of martyrdom.

All the other nuns are clearly defined, including the humane Mère Marie, whom Constance hopes will become the new prioress, and the person who does assume that role, Madame Lidoine, performed at the French-language premiere of the opera in Paris in June 1957 by the great soprano Régine Crespin.

Poulenc is perhaps best known for the ironic charm of his songwriting, and there is a lightness of touch in the way he writes for both orchestra and voice here, occasionally allowing the full force of the orchestra to be heard but often using smaller groupings of instruments. The vocal writing manages to feel affectingly natural, especially in the hymn-like passages of communal singing.

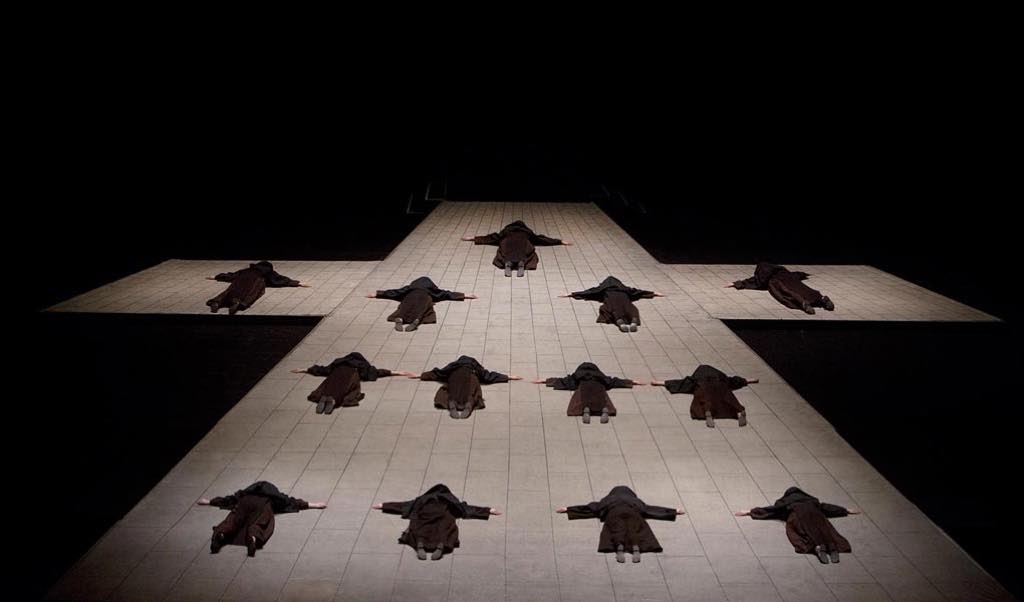

The final scene of the opera, in which the nuns, forcibly dressed in civilian clothes, walk to the guillotine singing the hymn to the Virgin, “Salve Regina,” could easily have lapsed into sentimentality, but Poulenc judges it perfectly. The repeated sound of the plunging guillotine blade above the orchestra is appropriately shocking, but even more moving is the thinning of the vocal texture as one by one each nun dies, eventually leaving just a single voice, that of Blanche, who, having run away, returns to take her place alongside Constance.

I have been lucky to see a number of interpretations of this scene, from a gory staging with heads dropping into the darkness at each schlang! of the guillotine at the Santa Fe Opera Festival to the traditional but theatrically effective departure from the stage of each nun at the New York Met, which can be seen in an earlier incarnation here, to the much more abstract rendering at Covent Garden, directed by Robert Carsen, similar to this clip from a Dutch National Opera production, also directed by Carsen.

A sign of the greatness of Dialogues des Carmélites is that such diverse interpretations can all be deeply affecting.

Nick Hammond’s latest book, The Powers of Sound and Song in Early Modern Paris, is now available in paperback and as an e-book here and from online vendors.

Favorite