Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986) is mega-famous in the United States for her flower paintings, almost to the point of oversaturation, but the current retrospective at Paris’s Centre Pompidou shows just how much more there was to the work of this versatile artist than brightly colored closeups of outsized blossoms. It also introduces her to France, where she has never before been the subject of a major exhibition.

The Pompidou show makes it clear that O’Keeffe’s work was bold and colorful right from the beginning and that she was an American pioneer of abstraction. The paintings from “Series I” (1918-19), for example, may represent waves and flowers, but they verge on abstraction. “Red Streak” (1919) may have been inspired by the sights and sounds of the plains of Texas and have a suggested horizon, but it is really pure abstraction. Her wonderful and subtle “White Abstraction” and “Black Abstraction” (both 1927), painted long before the Abstract Expressionists got down to it in the 1940s, have no discernible subject matter.

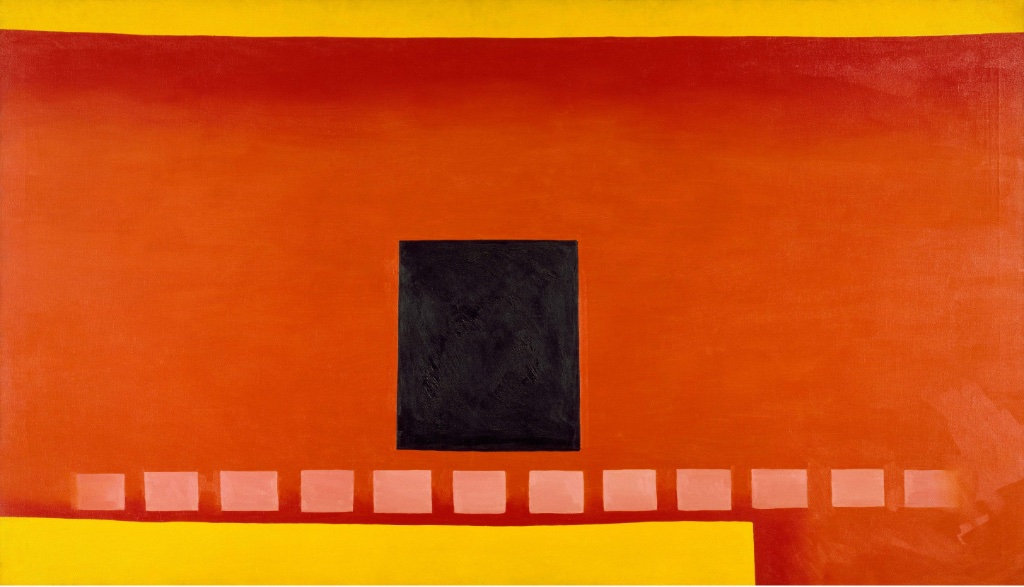

While she never limited herself to abstraction, painting what she saw in the way she interpreted it, her later paintings go even further toward abstraction. Examples are “Black Door with Red” (1954), in which the door of her house is distilled into a black square (pictured at the top of this page), and “Winter Road I” (1963), in which the road simply becomes a ribbon of black against a white background.

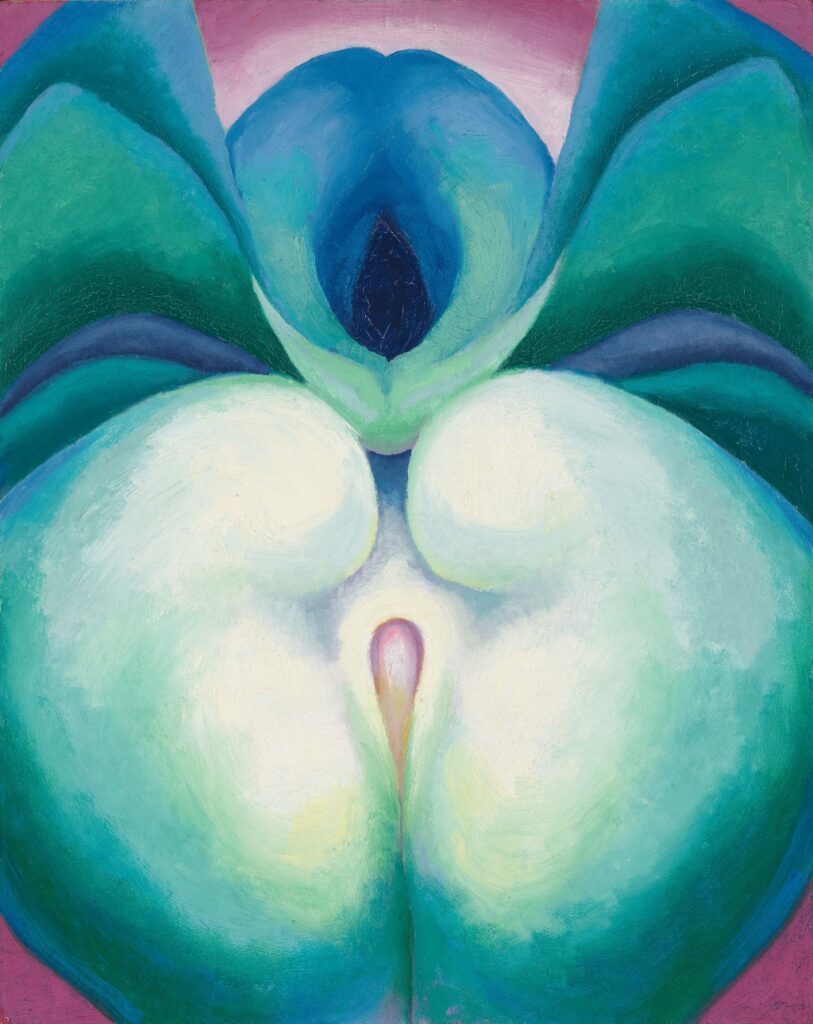

The question often comes up of whether O’Keeffe’s flowers were symbols of female genitalia, something she was often accused of – or praised for – depending on the commentator’s point of view. She always denied any such intentions, claiming that she was just painting flowers and that any sexual interpretations of her work were coming not from her but from the eye of the beholder.

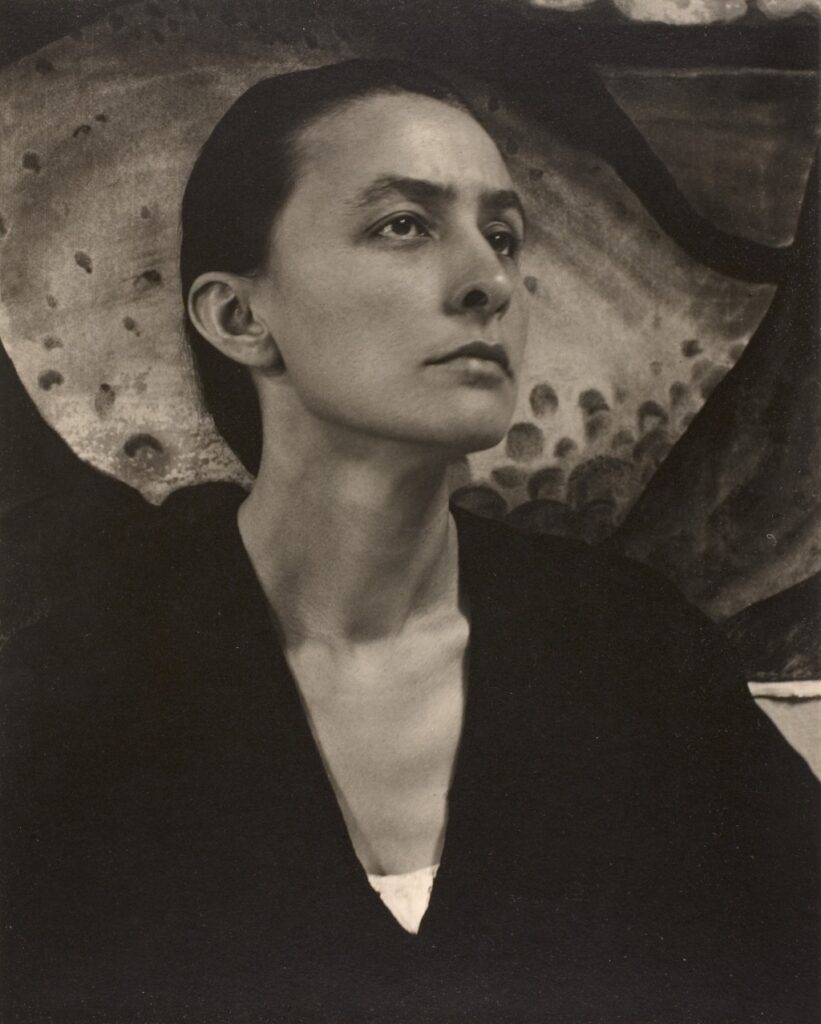

O’Keeffe is famous not only as a painter, however, but also for her relationship with her much older husband, the photographer and art dealer Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946), who gave her her first exhibition (of drawings) at his Galerie 291 in New York in 1917 (before they had a relationship) and made her even more famous through his photos of her, many of them nudes, which created a scandal at the time.

It’s interesting that the biographies of famous women artists – among them O’Keeffe, Frida Kahlo and Louise Bourgeois – seem to take on as much importance as their work. Anyone who has seen a Kahlo show knows about her love and devotion for Diego Rivera and the accident that wrecked her body and caused her so much pain for the rest of her life, and anyone who has seen a Bourgeois show knows that she was molested by her father as a child and had an intense relationship with her mother, things she continued to work out in her art throughout her life.

O’Keeffe also had a fascinating, if less dramatic, life, but she does not seem to have used her paintings to work out her psychological problems, even though she certainly had some hard times in her life. In the 1930s, for example, distraught by Stieglitz’s affair with another woman, she stopped painting for a few years and spent time in a psychiatric hospital.

A painter’s painter, she was interested in what she saw and inspired by sounds and music. And she wanted to be considered simply an artist, not a “woman artist.”

Her life story is inspiring, especially as she grew older and asserted her independence. Don’t miss the filmed interview at the end of the exhibition, in which she exudes serenity and self-confidence. When the interviewer says that it was “nice” of Steiglitz to let her go to New Mexico every summer (whose landscapes she fell in love with, inspiring her to eventually move there for good), she says, “He didn’t ‘let’ me; I just went.”

During the interview, she also offers an analysis of the good fortune she had had in her life – one that everyone, but especially women, should heed – saying, “Maybe it’s because I’ve taken hold of anything that came along that I wanted.”

O’Keeffe’s huge, well-deserved popularity, like that of Kahlo and Bourgeois, would seem to indicate that the world is hungry for and receptive to great women artists. Don’t miss this uplifting show.

Favorite

Such an astute observation about women artists’ biographies getting more focus than their works. I’m guilty of that myself in my art columns for NPR. I suspect it’s that several women were partners of forceful, dominant men who attracted all the press attention. In recent years, the women are getting more (and justified) attention. Thanks for this excellence piece on the much-exposed O’Keeffe.

Thanks for your insights, Susan!