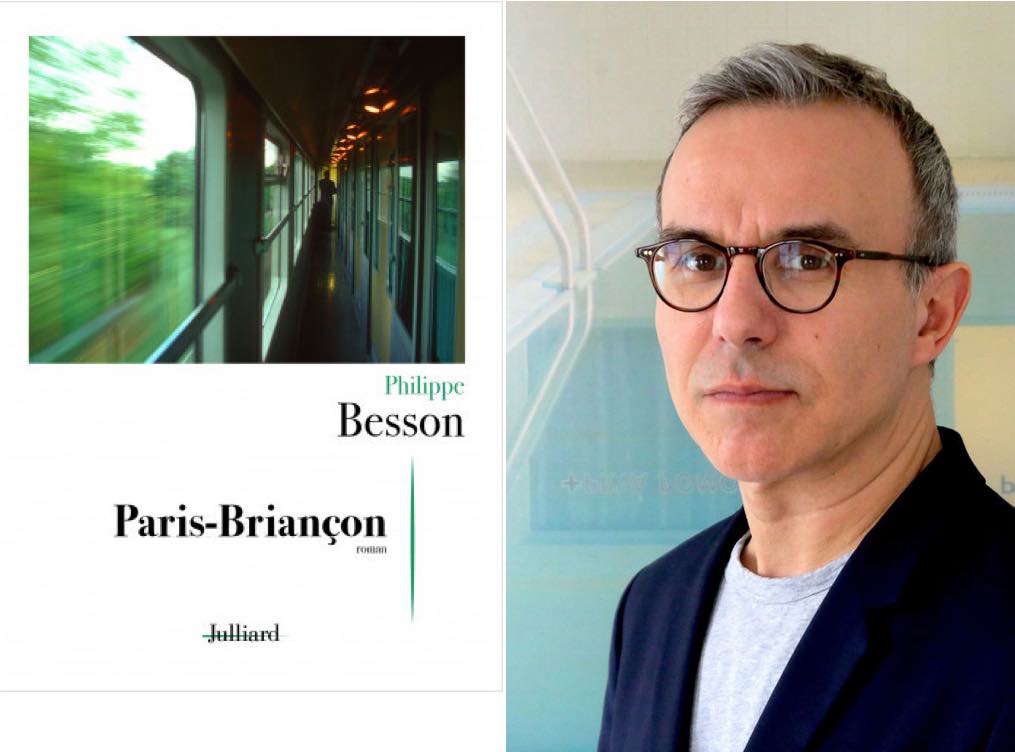

When we are informed at the beginning of Philippe Besson’s new novel, set on the overnight train from Paris to Briançon, that there will be deaths by the time dawn breaks, it would not be a complete surprise to find Hercule Poirot, waxed mustache and all, popping his head around the compartment door to comment on the travelers’ suspicious activities. Fortunately for Besson fans, Paris-Briançon turns out not to be an Agatha Christie pastiche but rather a subtle and humane exploration of a group of characters whose lives are arbitrarily thrown together for a period of a little over 10 hours.

When a colleague and I interviewed Besson shortly before the publication of Paris-Briançon, he commented on his interest in bringing together people who would never have met in any other circumstance, and in the role played by chance or even providence in the intimacies they reveal to each other in a restricted setting in the darkness of the night.

Where Besson excels is in bringing out the complexity of his characters, each of whom is traveling to Briançon in the Alps for very different reasons. One is a 40-year-old gay doctor who is returning to sort out his recently deceased mother’s house. He finds himself in the same carriage as a 28-year-old ice hockey player who is rather too insistent upon telling his travel companion about the girlfriend who will be waiting for him at the station.

In another carriage, a 34-year-old television production manager, traveling with her two young children, is leaving an abusive relationship. During the journey, she forms an unlikely bond with a married 46-year-old ski merchandise salesman, who, despite initially seeming to be an unsavory character, reveals unexpected depths.

Perhaps most disarming of all is the friendship struck up between a married couple in their 60s and five young students in the adjoining sleeper. What begins as a complaint by the couple about the noise being made by the students ends with them playing cards together and discovering complicity that would not at first have seemed possible.

The author’s decision to let us know about the impending deaths early in the book works well. It not only influences the way we read the novel – how will the deaths occur? who will be responsible for them? – but also makes us relate differently to the characters themselves, knowing that some of them will die and others will not. The denouement came as a poignant surprise to me.

Besson, whose wonderful autofictional work Arrête avec Tes Mensonges (Lie with Me) is being made into a movie, set to appear next fall, clearly has an eye on the cinematic possibilities of this new work, much of which consists of dialogue between the different characters, which would translate well to the screen. As a novel on its own terms, it is radically different from anything that he has written before, but it still manages to be affecting, humorous and refreshingly unexpected, with not a waxed mustache in sight.

Nick Hammond’s latest book, The Powers of Sound and Song in Early Modern Paris, is now available in paperback and as an e-book here and from online vendors.

Favorite