I must admit to approaching British director Richard Jones’s production at the Opéra Bastille of Richard Wagner’s Parsifal with some trepidation. Jones’s previous productions of Wagner’s other works, especially the Ring Cycle, have had a tendency to trivialize the most profound moments, as if he were determined to look at the action with an ironic eye.

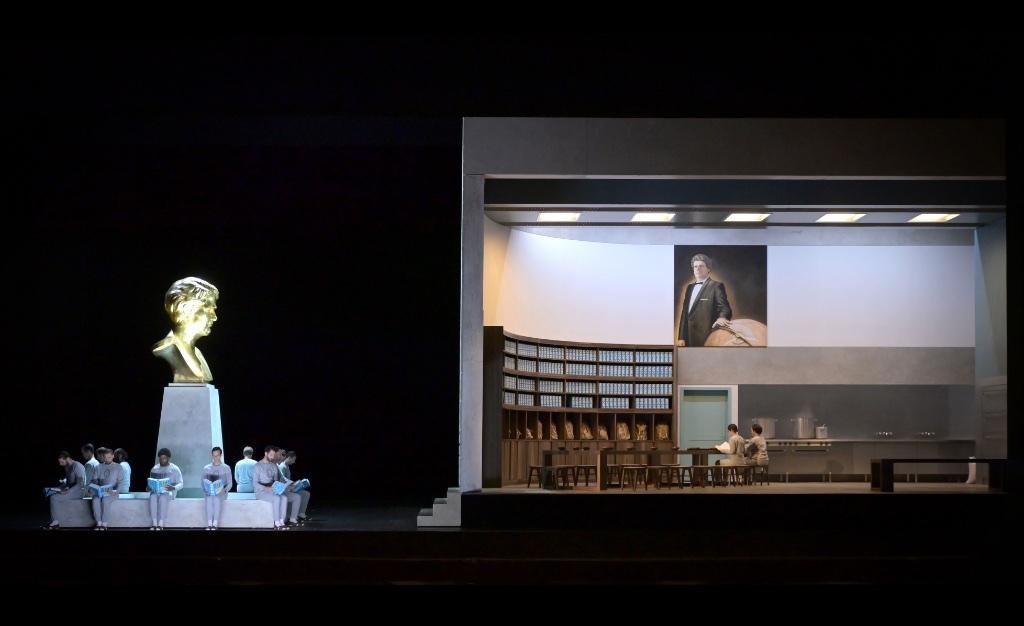

When the curtain rises on this production of Parsifal, the setting suggests that the Knights of the Grail are part of a mid-20th-century cult. The stage is dominated by a huge golden bust and portrait of their leader, Titurel, and each of the knights is reading a thick tome entitled “Wort” (“Word”), copies of which adorn the shelves, no doubt containing the writings of their Dear Leader. Given the arcane ceremonies that the Knights perform over the course of the opera, Jones’s idea initially does not appear to be a bad one. However, in order for it to succeed over the course of such a monumental piece as Wagner’s final opera (with two intervals, it runs at well over five hours), that idea needs to work in tandem with the music, and this is where the production fails. Since Jones cannot possibly think that the miracles performed by this brainwashed cult are genuine, his staging contradicts the searing sincerity and seriousness of the music, especially in the final act.

Luckily, the committed singing of the soloists and chorus, and the beautifully modulated playing of the Orchestre National de l’Opéra de Paris under the baton of Simone Young made the evening a triumph musically. I have been attending Wagner operas for many years, but, scandalously, Young is the first female conductor of Wagner I have come across. Let us hope that her excellent direction and sensitive shaping of the musical line will inspire not only up-and-coming female conductors but also opera-house directors who hire conductors for forthcoming operas.

In spite of my reservations about the staging, it must be said that, visually, Jones and his set designer, Ultz, have a strong sense of theatricality. The enormous stage set, which moves horizontally in the first and third acts, and the gaudiness of the second act (where the Flower Maidens, who all sing sumptuously, are depicted with grotesquely oversized breasts and genitalia in their attempts to seduce Parsifal) are certainly memorable in their way, even though the parents who had brought their children to the opera might have been regretting that decision.

In the title role, New Zealand tenor Simon O’Neill sings with intelligence and sensitivity, negotiating the increasingly difficult vocal writing with aplomb, even though his tone lacks the pure beauty of some previous performers of the part. Starting out in ill-fitting schoolboy attire, Parsifal’s evolution from seeming simpleton to savior of the Grail brotherhood is convincingly depicted.

Russian mezzo-soprano Maria Prudenskaya, whose overacting in the first act did not augur well for the pivotal second act, gives a thrilling vocal performance when it matters, no more than in her varying attempts to seduce Parsifal.

Of the many bass and baritone parts that dominate the remainder of the cast, Kwangchul Youn stood out with his burnished voice and quiet nobility. His long solos in the first and final acts are models of pacing. As the guardian of the Grail, Amfortas, whose wound will not heal until Parsifal secures the spear, Brian Mulligan sings with understated grace. Falk Struckmann as the fallen knight and sorcerer Klingsor is appropriately menacing and shows his long experience in the role. Particular mention should also be made of young bass William Thomas, whose vocally accomplished performance as second Knight of the Grail bodes well for future, more central operatic roles.

Nick Hammond’s latest book, The Powers of Sound and Song in Early Modern Paris, is available in paperback and as an e-book here and from online vendors.

Favorite