I felt great gratitude to the Fondation Louis Vuitton on my way out to the Bois de Boulogne to see its two new exhibitions: “Ellsworth Kelly. Shapes and Colors” and “Matisse: The Red Studio.” Why? Because the subject was not sports, as it is of seemingly all other art shows being held at Paris museums in the run-up to the Paris Olympic Games. For those of us not sportingly inclined, it’s a relief.

The foundation is celebrating the centennial of Ellsworth Kelly’s birth with a show of the work of one of the great abstract artists of the 20th (and a bit of the 21st) century.

I was unaware that in the post-World War II period, Kelly, like many other American artists at the time, had taken advantage of the G.I. Bill to live and study in Paris (from 1948 to’54), where he immersed himself in the international art community, meeting the likes of John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Jean Arp, Constantin Brâncuși, Francis Picabia and Alberto Giacometti.

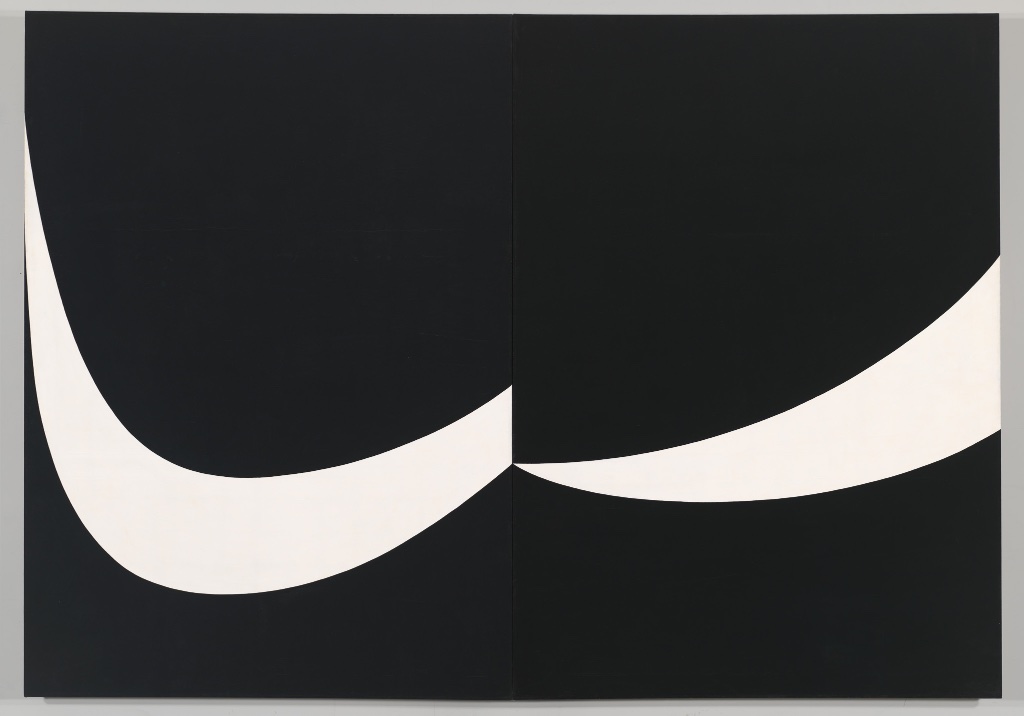

You can’t get much more abstract than Kelly’s works, but the first part of the exhibition shows how his early abstractions were inspired by actual sights he saw in France, though you would never know if it weren’t explained to you. He transformed the Seine into little black-and-white cubes, for example, and turned a squat toilet and a kilometer marker from a French road into graphic shapes. For another painting, he sketched the shadows cast by a staircase handrail throughout the day and transferred them to canvas and then to a folding screen. These two works can be seen in the above photo.

Kelly liked to think of the wall behind his paintings as an integral part of the work and created sculptural effects on many of his canvases before starting to make actual sculptures, a few of are on display in the show. The exhibition also includes his lovely drawings of plants, his very graphic black-and-white photos and his amusing collaged postcards.

The exhibition culminates with the site-specific works he created for the auditorium in Frank Gehry’s spectacular building for the Fondation Louis Vuitton: five monumental paintings of different shapes, sizes and colors that punctuate and animate the white-walled auditorium.

The major works in this show works are bold, colorful, attractive and striking, but – with the exception of the knockout “Yellow Curve,” which has its own room – don’t expect to experience the visceral effect that Mark Rothko’s paintings, for example, had on viewers in the foundation’s last show. Kelly’s intellectual approach to painting and flat expenses of color don’t draw you into his works the way Rothko’s paintings did. The latter created an intriguing sense of mystery by building layers of color and letting them interact with each other. Even Kelly’s contemporary, Robert Ryman (1930-2019), who is currently the subject of a lovely retrospective at the Musée de l’Orangerie, created more engaging works by using almost exclusively white or off-white pigments while changing the textures, formats and supports of his paintings.

The concurrent show at the foundation featuring one of Kelly’s heroes, Matisse, with whom he shared a love for intense color, should be a crowdpleaser. It’s based on a simple and appealing idea: display one of Matisse’s most famous works, “The Red Studio,” painted in 1911, in the same room with all of the 10 artworks that are depicted in it.

It wasn’t easy, however, to gather every one of those works – six paintings, three sculptures and one ceramic piece – at the same time for this traveling exhibition, which has already been shown at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, owner of “The Red Studio,” and the National Gallery of Denmark. Luckily, a serendipitous event made it possible: the MoMa curator who had the idea for the show called the National Gallery of Denmark to propose the idea only a few days after the Danish museum had acquired one of the paintings in question, “Bathers,” whose whereabouts had only recently been rediscovered.

“The Red Studio” is a revolutionary piece in Matisse’s œuvre. It was not the first painting he had made of his studio and its contents, but this time he did something that even he found strange: after painting the walls, furniture and artworks in various colors and in perspective and leaving the painting to rest for a while, he picked up his brush and went over the entire canvas with Venetian red paint, leaving only the artworks and the outlines of the furnishings visible. The painting’s flat red surface borders on abstraction, with vague representations of the artworks and a few objects floating on it. The curators see the painting as a “manifesto that makes color an artistic element in its own right, liberated from any narrative or representational function.”

It’s a fun exercise to compare the real artworks in the room to their sketchily depicted representations in “The Red Studio,” but I’m not sure what we learn from it.

The rest of the exhibition traces the journey of the painting, from the time it was rejected by Matisse’s patron Sergei Ivanovich Shchukin, to the Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition in London in 1912 and then to the Armory Show in New York, Chicago and Boston. We get to see other paintings that were exhibited with it in those shows and learn that “The Red Studio” was mostly the subject of ridicule at the time. The show ends with a splash with another stunning painting that echoes “The Red Studio” with its overall flat red surface, this one from 1948: “Large Red Interior.”

It wasn’t until 1949, when “The Red Studio” was acquired by MoMA, that its importance in the history of modern art was recognized.

When I got to the end of the Matisse exhibition, I saw a sign pointing to another show that wasn’t being played up by the foundation: “The Collection: A Sports Meeting.” Aha, so the foundation was not immune to Olympic fever after all. This minimalist show turned out to contain only a few works, beginning with a fascinating video installation, “Walk on Clouds” (2019), by Abraham Poincheval, in which the artist strolls through the sky, hanging from a mostly unseen hot air balloon, munching snacks carried in a backpack and surveying his kingdom – the clouds and earth below – with binoculars. This is an athletic feat of another kind. The following works in various media are by Andy Warhol with Jean-Michel Basquiat, Basquiat alone, Andreas Gursky, Roman Signer and Omar Victor Diop. Apparently, the foundation couldn’t resist going through its collection and picking out a few works related to sports. It’s worth a look, even for non-sporting types.

See our list of Current & Upcoming Exhibitions to find out what else is happening in the Paris art world.

Favorite