|

|

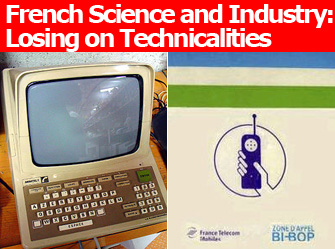

The Minitel and the Bi-Bop, the first “cellphone” in wide use in Paris: pull out the aerial and don’t move! |

The French can rightly be proud of their many contributions to technological progress, including the credit card with the embedded chip, the high-speed train and the even-higher-speed-but-currently-out-of-commission supersonic airliner. Nonetheless, most people don’t associate France with cutting-edge technology, perhaps because the country has a long history of bad luck in the R&D department. A great many French inventions have been not so much in the “Wow! What’ll they think of next?!” category as in the category of “I guess that’ll do until something better comes along.” And then something better comes along almost immediately, or in some cases already exists. Granted, I’m cherry picking here, but consider this timeline:

• 1793: France adopts the “Télégraphe” system, developed by Claude Chappe, for relatively rapid long-distance communication.

It involved building windmill-sized towers on hilltops within eyeshot of each other. On top of each tower was a set of semaphore vanes that operators used to spell out messages that were relayed from one post to the next. Obviously, it required major construction and could only function during the daytime in clear weather, but otherwise it was indeed faster than sending a document by horseback.

The first message sent was: “Hi, it’s me. I’m downstairs. What’s your building’s door code again?”

• 1804: Catalan scientist Francesc Salvà i Campillo and, a few years later, German inventor Samuel Thomas von Sömmering develop the first prototypes that would soon lead to the perfection of the electrical telegraph.

• 1883: French police inspector Alphonse Bertillon introduces a biometrical criminal identification technique that involves measuring ten more or less unchangeable corporeal features.

The idea was that no two people would have exactly the same dimensions of all 10 body parts. Of course, “Bertillonage,” as it was called, required painstakingly precise records involving multiple parameters to be kept by policemen, who even back then were well known for their fanatical devotion to accuracy and finesse in paperwork. Also, surprisingly few criminals saw fit to leave their body measurements at crime scenes, so it proved useless for detection but of some value in preventing mistaken or fraudulent identity.

• 1892: Charles Darwin’s cousin Sir Francis Galton develops a system for the analysis and classification of fingerprints.

• 1876: Alexander Graham Bell files a patent for his “talking telegraph,” and by 1916 the proportion of North American households equipped with a telephone reaches 75 percent.

• 1976: The proportion of Parisian households equipped with a telephone reaches 75 percent. (Source: a hat. I was surprised how hard it is to find the exact figures, but this must be pretty close to reality.)

Yes, it took a century. Why? Largely because Paris had the “pneu,” short for Poste Pneumatique: a system of pneumatic tubes that ran through the Métro tunnels and were used to send little canisters containing written messages. It was faster than mailing a letter and considered to be, for everyday purposes, every bit as efficient and convenient as talking on the phone. It wasn’t. But it wasn’t discontinued until 1984.

First message sent: “To whom it may concern: I trust my humble missive finds you well. My building is on fire. In the hope of your speedy reply, rest assured that I remain, faithfully yours, &c. (name and address obliterated by smoke damage).”

• 1972: HBO is founded, and cable television rapidly becomes commonplace in the United States, with many service providers offering dozens, if not hundreds, of channels.

• 1983: The first more-or-less equivalent of cable TV finally comes to France in the form of Canal Plus.

Subscribers had to install a bulky decoder box and pay a monthly fee of 140 francs (about €35 in today’s money), in return for which they could receive: one channel. This is not a typo. The advantage was supposedly that Canal Plus showed newer movies and more live sports events. It was shockingly successful and is still around, now with multiple channels, whereas cable TV never really took off in France until the spread of home computers and ISPs offering package deals on Web access plus television.

And speaking of the Internet…

• 1980: France Télécom introduces the Minitel, a kind of communication-dedicated home minicomputer.

For rates of up to €1 per minute plus the subscription fee, users could consult the White Pages, check their bank balances, make train reservations or join the repartee in a chat room on a tiny black and white lo-res screen without paying any more than they would for a conference call to Singapore!

• 1980 (again): This happens to be the exact same year that Compuserve began offering real-time chat on the Internet. Three years later AOL was making e-mail and an ever-increasing array of online services available to millions of subscribers for a flat monthly charge.

• 1983: Ameritech, the first cellphone network in the United States, is launched.

• 1993: France Télécom introduces a handheld semi-mobile phone called the Bi-Bop.

I say “semi-mobile” because to use it you had to be near an antenna, from which you couldn’t stray, whose proximity was indicated by blue, white and green stripes around light poles, which by the way are visible in Paris to this day. In addition to 1,890 francs (about €285 euros) for a terminal, subscribers paid a monthly rate of €8.50 plus €0.13 per minute for placing calls. At the time this was dirt cheap for cellphone service, but receiving calls required a specific, and more expensive, subscription.

The first call placed was: “Monsieur Ouatesonne, venez ici, je… Allo? Allo? Allo? Allo? Aaaaaa-llo…”

So what’s next from French technology? Lukewarm fusion? A not-quite-perpetual-motion machine that remains in action until the country’s entire population accepts the inevitability of later retirement ages? An uncannily realistic human-like robot with a lazy streak, an abrasive personality and B.O.? If we had a time machine, we could travel into the future and find out. But if it’s a French time machine we’ll probably have to send a sticky note into the future (multiples of 35 years only) asking whoever finds it to write down a list of recent inventions and send it back. By horseback.

© 2010 Paris Update

Favorite

An album of David Jaggard’s comic compositions is now available for streaming on Spotify and Apple Music, for purchase (whole or track by track) on iTunes and Amazon, and on every other music downloading service in the known universe, under the title “Totally Unrelated.”

Note to readers: David Jaggard’s e-book Quorum of One: Satire 1998-2011 is available from Amazon as well as iTunes, iBookstore, Nook, Reader Store, Kobo, Copia and many other distributors.