An exhibition about a little-known 16th-century German artist doesn’t sound like a barrel of laughs, but “Albrecht Altdorfer: Master of the German Renaissance” at the Louvre turns out to be surprisingly entertaining thanks to the sheer exuberance and diverse talents of this prolific painter, engraver and architect.

The names of Altdorfer’s contemporaries and rivals, Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) and Lucas Cranach (1472-1553), have gone down in history in a way that Altdorfer’s hasn’t, and one wonders why after seeing this show. Altdorfer was born in Bavaria around 1480 and died in 1538.

Little is known about Altdorfer’s early training, but it is clear that he was familiar with Dürer and Cranach and also with the artists of the Italian Quattrocento, notably Andrea Mantegna, thanks to widely circulated prints of their works. The ambitious artist did not slavishly copy their work but “emulated” them, making images that were very much his own.

While he may not be well known to us, Altdorfer was a great success in his lifetime and became one of the official artists of Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I.

The chronological exhibition, interspersed with thematic sections (landscapes, architecture, etc.), includes some 200 works and situates Altdorfer in his time by including works by his contemporaries, including Dürer and Cranach, and – a discovery for me – the Austrian artist Wolf Huber (c. 1485-1553), like Altdorfer a painter, printmaker and architect (Altdorfer and Huber, the leading figures of the Danube School, were among the first to paint landscapes and architectural interiors for their own sake, devoid of figures).

It also shows how his work grew and changed over time. His early works are striking for their oddness, with deformed, often ugly faces on the figures, even in religious scenes, as in “Holy Family with a Deacon” (1507), in which the Virgin, with a puffy face and beady eyes, looks rather dim, while Joseph could well be a psycho-killer and the chinless deacon a fool.

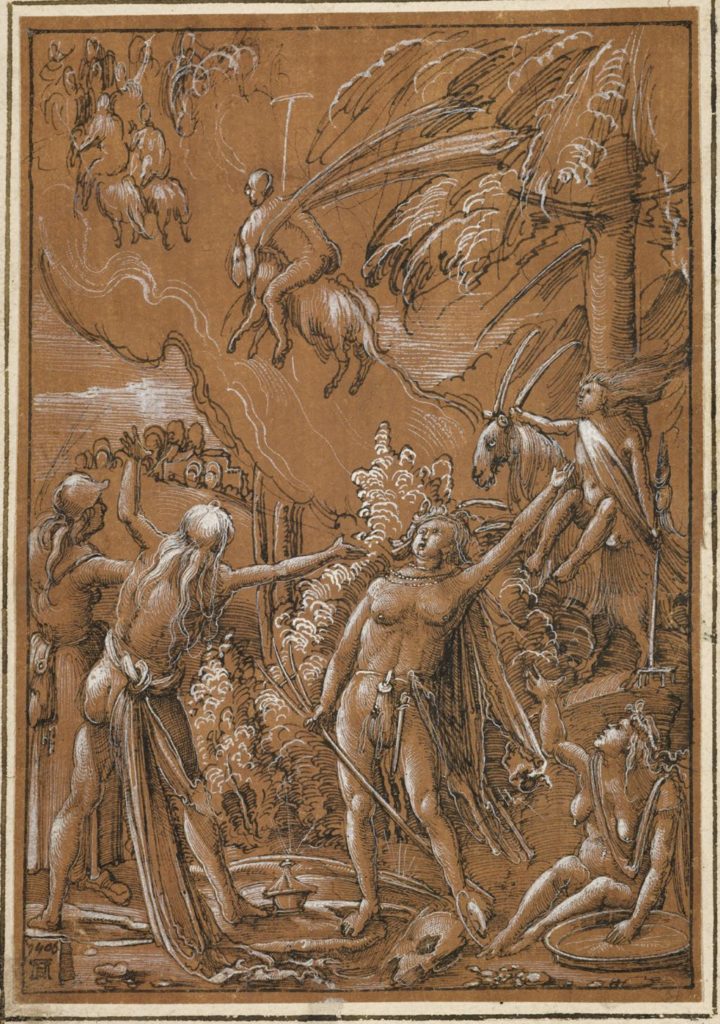

One of Altdorfer’s early chiaroscuro drawings, “Departure for the Sabbath” (1506), demonstrates his great expressivity and the fantastical nature of some of his works. Riffing on a subject popular at the time, it shows a gathering of half-naked witches flying off on goats to meet up with the devil in the desert.

As he grew older and more successful, his work became more refined, but his sense of drama remained, as seen in major narrative cycles depicting the life and passion of Christ and the legend of Saint Florian, full of action and vibrant color.

Take the time to study the “Triumphal Procession,” a series of woodcuts commissioned by Maximillian I from several artists. While the 39 prints by Altdorfer shown here may look similar from a distance, with their horses, riders and banners, a close look shows that each rider is individuated, with distinct features and attitudes, and even the horses are differentiated from each other, sometimes neighing or turning to look at each other. Every one of the prints teems with detail (not taken from life, by the way, as this procession never took place), even on the banners, which are also lavishly illustrated.

This incredible attention to detail is even more obvious in two battle scenes, “The Victory of Charlemagne over the Avars” (1518) and “The Battle of Alexander at Issus” (1529; shown here in a video presentation), with their multitude of figures and dramatic skies in the background.

Artwise, Altdorfer seems to have done it all, in great quantity. Take your time and take it all in.

Favorite