Algeria is currently in the spotlight here during the 60th anniversary year of the Évian Accords, which ended the bloody eight-year-long Algerian War and led to Algeria‘s independence from France. One very welcome commemoration of this historical moment is the exhibition “Algérie Mon Amour” at the Institut du Monde Arabe, featuring modern and contemporary artworks by Algerian artists, whose works decidedly deserve to be shown here more often.

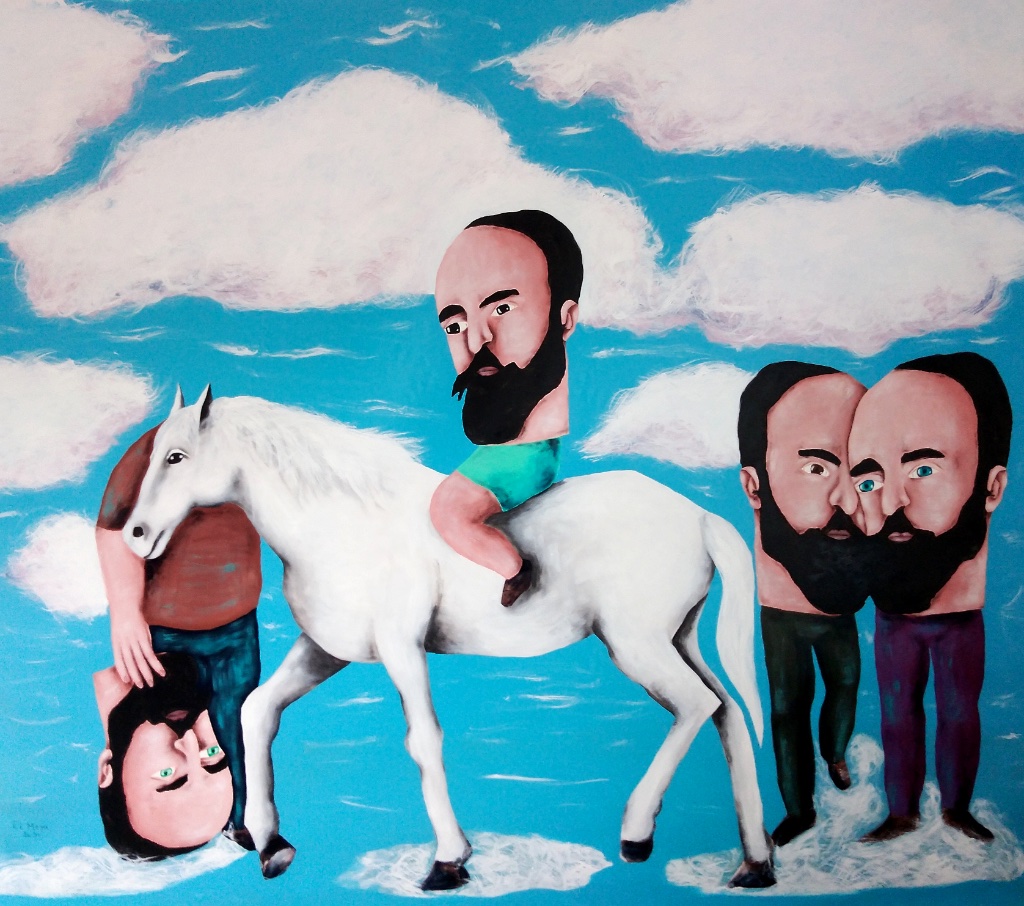

Not surprisingly, most but not all of these works are political in nature, although the message might not be obvious straightaway. Immediately striking and pertinent to the anniversary is the recent (2021) painting “Portrait de l’Émir Abdelkader” by El Meya (real name: Maya Ouarda Benchikh El Fegoun), depicting a 19th-century hero of Algerian resistance to French colonization. His image is a common sight in Algeria, but in this multiple portrait, the artist strips him of all his usual heroic attributes, most of his clothes and even his arms and, in one version, his head, which he holds upside-down in his hand. All that is left of the usually recognizable turbaned figure is his familiar black beard and his white steed.

Another artist whose work quickly draws the eye, pulls it in and holds it is Denis Martinez (born 1941), whose work Jack Lang, director of the Institut du Monde Arabe, refers to as “virtuoso primitivism.” Martinez is represented here by two energetic large-format paintings full of vividly colored patterns and shapes: arrows, squares, circles, triangles and more, some of them coming together to form recognizable figures, such as a human face or a lizard. Each work seems to contain magical messages that keep the viewer searching in fascination among what look like symbols, and indeed there are messages to be found, for the artist is also a poet: “Ramène la raison devant chaque porte” (“Bring reason to every door”), is written on “Anzar (Le Prince Berbère de la Pluie),” (2001), which also contains incantations in the Berber alphabet, Tifinagh, calling for rain and, metaphorically, peace in Algeria as the civil war neared its end. Martinez’s syncretic style is also influenced by the age-old art of tattooing, a tradition still passed on by Algerian women.

On a seemingly calmer note, Abderrahmane Ould Mohand’s “Le Jardin des Moines” (“The Monks’ Garden,’ 1997) presents a flattened view of a picnic spread out on a checked tablecloth, calling to mind the “Déjeuner sur l’Herbe” scenes by Manet and Monet, even though there are no people at this picnic. On the cloth are various fruits, some dishes, a wine bottle and an open book, which also offers a written message: “Frères, tout homme est une histoire sacrée” (“Brothers, every man is a sacred story”). Below this simple scene painted in a naive style is another, a landscape seen from afar. Look closely, and you will see the first names of the seven monks written on the earth.

In fact, this bucolic scene is the artist’s poetic way of representing the frugal meal that might have been enjoyed by the seven monks at the Our Lady of the Atlas Abbey in Tibhirine, Algeria, who were massacred in 1996 during the Algerian Civil War, which explains why there is no one in the image. (An excellent film on the subject, Des Hommes et des Dieux, or Of Gods and Men, was made by Xavier Beauvois in 2011).

With 36 works by 18 artists in a range of styles and media, this small exhibition is highly recommended as an introduction to a group of artists living in Algeria and abroad, two of whom – Mahjoub Ben Bella and Rachid Koraïchi – are, ironically, known throughout the world but not in Algeria or France. They all have a lot to say, and they say it forcefully and beautifully.

Favorite