|

|

|

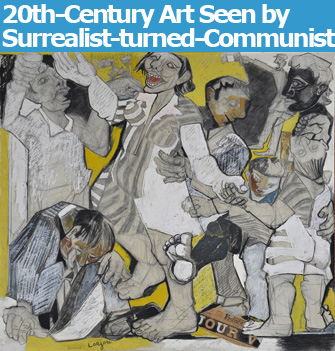

“Le Jour V” (1945) by Bernard Lorjou. © Adagp, Paris 2010. Photo © Jean Bernard |

One of the founders, with André Breton and Philippe Soupault, of the Surrealist movement in 1924, Louis Aragon (1897-1982) was a …

|

|

“Le Jour V” (1945) by Bernard Lorjou. © Adagp, Paris 2010. Photo © Jean Bernard |

One of the founders, with André Breton and Philippe Soupault, of the Surrealist movement in 1924, Louis Aragon (1897-1982) was a poet, novelist, journalist and editor whose name is recognized by just about everyone in France, where his literary works are still studied in schools. For non-French visitors for whom he is something of a mystery with a vaguely familiar name, however, the current exhibition at Paris’s Musée de Poste, “Aragon and Modern Art,” raises more questions about Aragon than it answers, concentrating as it does on one narrow aspect of his career, his writing on art.

Here, then, is a little background information on the man. After flirting with Dadaism and then moving on to Surrealism, Aragon broke with Breton and the Surrealist movement and joined the French Communist Party in 1927, under the influence of his wife, the Russian-born writer Elsa Triolet. He remained a member of the party until his death, although he moved away from party orthodoxy after the events of May 1968. He and Triolet were active in the Resistance during World War II. While he espoused Socialist Realism after his conversion to Communism, he continued to use Surrealist techniques like collage in his writing. Many of his poems were set to music by singers like Léo Ferré and Georges Brassens and were thus etched into the French popular imagination.

Aragon often presciently championed the work of young artists whose careers later took off, and he wrote about art with an admirable clarity (he despised art critics and refused to qualify himself as one). He wrote, for example, that Paul Signac had “understood better than anyone else” the way that color operates in nature, allowing “a piece of canvas and a bit of wood to suddenly take on the cachet of gemstones.”

The exhibition at the Musée de Poste is itself studded with gems, presenting around 40 works by artists that Aragon wrote about at one time or another, thus tracing his move from Surrealism to Social Realism, beginning with works by notable Dadaists-turned-Surrealists like Max Ernst, Man Ray and Jean Arp. Then come Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró (here represented by some refreshingly unfamiliar works on paper), André Masson, Yves Tanguy, Giorgio de Chirico, Paul Klee, Albert Giacometti, Marcel Duchamp (represented by the famous mustachioed Mona Lisa, “L.H.O.O.Q.), Bernard Buffet and others. The Social Realists he championed have less familiar names like Alekos Fassianos, Bernard Lourjou, Boris Taslitsky, André Fougeron and Marcel Gromaire, but they, too, offer some pleasant surprises, among them a Hopperesque painting by Bernard Moninot, “Station Service,” which impressed Aragon with its “figuration of silence.”

We also see books by Aragon illustrated by everyone from Picasso and Matisse to Tanguy, clippings from the various newspapers he edited and wrote for (with, notably, a portrait by Picasso of Stalin published when the dictator died, which got Aragon into hot water because it displeased the party leaders), plus a re-creation of a room in his home, which he turned into a kind of live-in bulletin board covered with photos, poems, postcards and memorabilia after the death of Triolet in 1970.

Toward the end of his long life, Aragon returned to the work of one of his many artist friends, Matisse, and wrote a novel entitled Henri Matisse, Roman.

This lovely little show offers a look at 20th-century art in France from the perspective of one well-placed viewer with friends in high places and a very particular viewpoint. You will want to know more about this man after seeing it.

Musée de la Poste: 34, boulevard de Vaugirard, 75015 Paris. Métro: Montparnasse-Bienvenüe, Pasteur or Falguière. Tel.: 01 42 79 24 24. Open Monday-Saturday, 10am-6pm. Closed Sunday and public holidays. Admission: €6.50. Through September 19. www.ladressemuseedelaposte.fr

Reader Thirza Vallois writes: “The singer even more connected to Aragon (in so far that he brought out an entire CD devoted to Aragon, and it’s a gorgeous one soit dit en passant), is Jean Ferrat. I was a student in Paris in the 1960s and Jean Ferrat was one of the idols. His song “Nuit et Brouillard” was on everyone’s lips in those days (of course we didn’t know at the time that he was Jewish and that his own father had died in the camps). Unlike Brassens, Jean Ferrat was a communist and in symbiosis with Aragon ideologically too. Brassens (who, by the way, is my own personal idol above them all), espoused no ideology (see his “Mourir pour des Idées”, which I love, but the message of which can be argued against in certain cases). Brassens was anti-Nazi for sure, but he did not join the Resistance movement, for example. The CD’s title is “Ferrat chante Aragon,” and it shuttles with me between London and Paris. Some of the songs are shattering. And then there is his voice…”

Order books by and about Louis Aragon from Paris Update’s Amazon store at no extra cost. Click on your preferred Amazon location: U.K., France, U.S.

Support Paris Update by ordering books from Paris Update’s Amazon store at no extra cost. Click on your preferred Amazon location: U.K., France, U.S.

Reader Reaction: Click here to respond to this article (your response may be published on this page and is subject to editing).

More reviews of Paris art shows.

© 2010 Paris Update

Favorite