Note to readers: You may choose to read this review of Philippe Besson’s Arrête avec Tes Mensonges (Lie with Me) here or listen to it on the audio file at the end of the article.

Over the last few weeks, I have been revisiting some classics of French literature and have tried to explain why and how they have had such an enduring legacy. This week, I am going to do something rather different and discuss a book that was only published three years ago. When it came out, I intended to write a review for Paris Update, but the experience of reading it was so visceral and affecting that I felt unable to distance myself enough to compose an objective and considered appraisal. The book is Philippe Besson’s Arrête avec Tes Mensonges, literally translated as “stop telling your lies,” but rendered rather beautifully and enigmatically by the American actress/writer Molly Ringwald as Lie with Me in her 2019 translation, which is now available in paperback.

There has been much talk in the English-speaking world about the recent BBC adaptation of Irish writer Sally Rooney’s phenomenally successful novel Normal People, which charts the different stages of a relationship between two people from different class backgrounds, Marianne and Connell, starting in secret in high school and continuing at Trinity College in Dublin. I mention this because Philippe Besson’s book is similar in that it begins with a clandestine relationship between two 17-year-old boys from different backgrounds at the same school and then reconsiders that liaison at a later stage.

Arrête avec Tes Mensonges is ostensibly autobiographical. The title refers to the words used by Besson’s mother about his habit as a child of making up stories, something that later became central to his life as a novelist. However, as the author mentions on the back cover of this book, “Today I am obeying my mother and telling the truth. For the first time.” Anybody who has ever read the many kinds of prefatory writing that introduce works of literature over the centuries will know not to take such assertions at face value. Indeed, even though many of the facts about the narrator’s childhood in a small town in Charente and his subsequent literary career perfectly reflect the trajectory of Besson’s life, the narrator tells us at regular intervals that he is inventing or reimagining scenes, even at one point using the word “lies” to describe what he has just recounted. We are in the familiar territory of much 20th– and 21st-century French writing: “auto-fiction.”

The first part, set in 1984, and by far the longest section of the book, recounts the furtive sexual meetings between the bookish, somewhat effete Besson, who is the son of teachers and is in the academic class at his high school, and Thomas Andrieu, half-Spanish and from a family of farmers, who is in the non-academic class at the same school. Despite the fact that the two boys have never spoken a word to each other (and will continue not to do so in front of others), Thomas seems to have picked Philippe out so that he can give expression to his sexual desires, which he is unable to admit to anybody else. When they first meet, at Thomas’s behest, in a café at the edge of the town of Barbezieux, Philippe asks why Thomas has chosen him rather than another boy. His response – “because you will leave and the rest of us will stay” – proves to be remarkably prescient: Besson himself had not even envisaged leaving at that point.

Besson’s prose here, as in many of his other novels, has a brutal clarity and simplicity as it maps the one boy’s inarticulacy and concealment, and the other’s acceptance of his sexuality and inner musings on the significance of their encounters. After their baccalauréat, when the two boys go on an outing in the countryside together, Thomas has already decided, without telling Philippe, that this will be their final meeting. While Philippe goes on to further academic and then literary success, Thomas leaves to work in Spain before returning to the family farm.

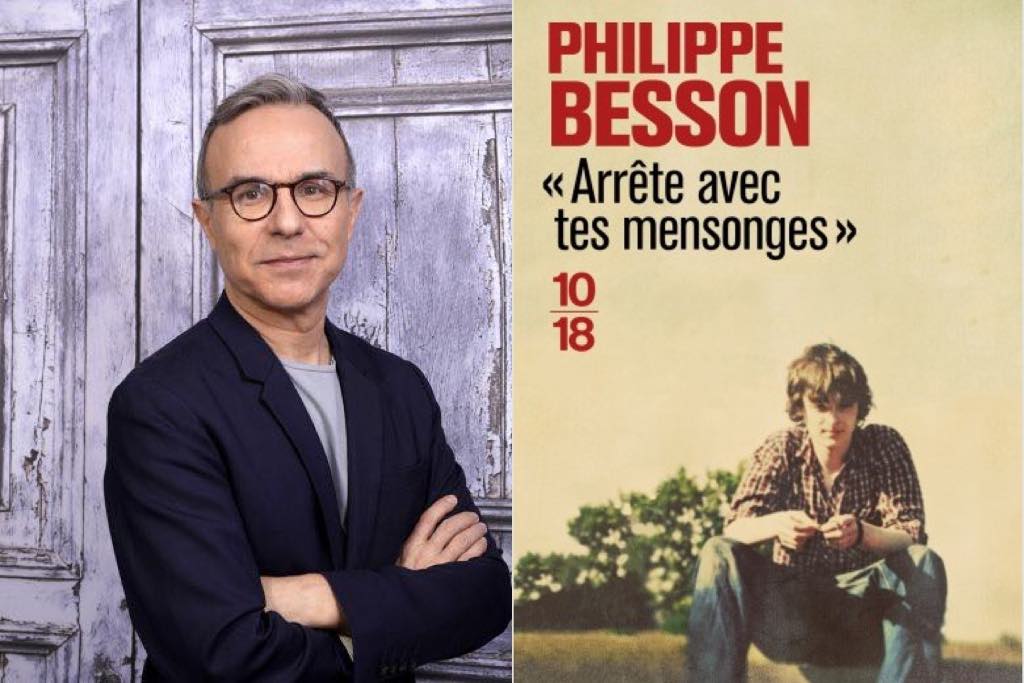

Besson is particularly good at describing photographs (he does this to wonderful effect in an early novel, Un Garçon d’Italie). The cover photo on the French edition of the book reproduces his description of the picture taken on the last day the two spent together: “In this photo, he is wearing jeans, a checked shirt with the sleeves rolled up, holding a small blade of grass between his fingers. And he is smiling. A light, complicit, and (I think) tender smile” (my translation).

The last two parts of the book take place much later, in 2007, when the now successful novelist mistakes Thomas’s son Lucas for the younger Thomas when he spots him at a book launch, and then in 2016, when Lucas and Philippe meet again. I will not spoil the ending for those wishing to read this wonderful novel, but it is one of the most poignant and perfectly judged conclusions to a book that I can remember.

Arrête avec Tes Mensonges turned out to be the first of a series of three pieces of auto-fiction, with Un Certain Paul Darrigrand appearing in 2018 and Dîner à Montréal in 2019. Although these two later books have wonderful moments in them, they do not to my mind have the intensity of the first one.

A movie version of “Arrête avec Tes Mensonges, directed by Olivier Peyon, is due to start filming this summer, although the Covid-19 pandemic may affect the shooting schedule. I for one cannot wait to see it, and I plan to write a review when it appears.

Audio Player Favorite

Might you be able to do some reviews of French literature in French?

Which leads me to ask how can we get French people to speak to fluent French speakers in French and not immediately switch to English? My French is excellent, but there is a trace, and everyone tells me absolutely minimal trace, of English accent. I find that so often as soon as this is detected the person with whom I have been speaking in French for five minutes decides that they have to switch to (often very poor) English, as if they can’t accept that an English person can actually be very very good at French. Anyone else had this?

Dear James,

I certainly empathize with your desire to read articles in French, but Paris Update is specifically an anglophone site. My series on literature was intended to encourage readers to discover new works. Good luck with getting replies in French!

Best wishes,

Nick