Racine’s play Bajazet, first performed in 1642, differs from the 10 other tragedies he wrote in one major respect. Whereas all the other plays are set in a distant timeframe – in ancient Greece or Rome, or in ancient biblical settings – Bajazet depicts unusually contemporary events, when the Ottoman sultan, Murad IV (Amurat in Racine’s version), had his rivals murdered in 1635.

In his preface to the play, Racine justifies such a choice of subject by arguing that the geographical distance from France of the Ottoman Empire and its people’s very different customs and morals made it seem as if they were from ancient times: “Tragic characters should be regarded with a different eye from the way we usually regard characters we have seen at close quarters,” he writes.

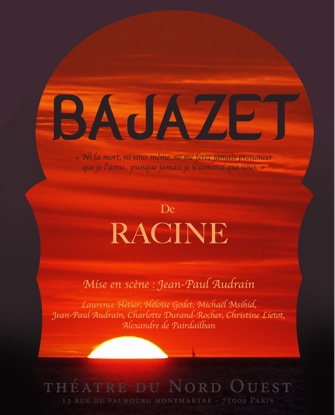

Whether or not because of this unexpected setting, Bajazet remains one of Racine’s most rarely performed pieces, and so it was with eagerness that a Racineophile friend and I rushed to watch this latest production by Jean-Paul Audrain, part of the series of Racine’s complete works currently being staged at the Théâtre du Nord-Ouest.

Having recently reviewed an opera in which its director relied on a large number of huge digital screens to communicate and, in some cases, confuse the audience, I was relieved and delighted to find that Audrain uses a completely bare set with no backdrops of any kind and that the message conveyed is clear and affecting. The many doors that lead onto the theater’s main stage provide sufficient drama to keep the spectator engrossed and intensify the play’s setting in a harem.

Racine made the brilliant choice of keeping Sultan Amurat off the stage entirely as he lays siege to Babylon, a task believed by his favorite, Roxane (played by Laurence Hétier), and the Grand Vizir Acomat (performed by Audrain) to be futile. The absent Amurat dominates the action as messages and rumors about the outcome of the siege are relayed to the characters trapped in the harem.

In gambling that Amurat will be defeated, Roxane, who has been given temporary political control by the sultan, sets her sights on Amurat’s brother Bajazet (Michael Msihid), while Acomat hopes to marry Atalide (Héloïse Godet). The only problem is that Bajazet and Atalide are in love with each other, even though they know that Bajazet’s survival depends on his acquiescence to the wishes of the ruthless Roxane.

It all makes for great drama, and, although this production’s sometimes overlong pauses upset the natural rhythm of Racine’s alexandrines (12-syllable lines of verse), the actors perform their roles magnificently. Racine specializes in strong female roles, and Roxane is one of the fiercest of them, played with appropriate passion but also with a touching vulnerability by Hétier. All the other parts often pale by comparison, but Audrain as Acomat and Godet as Atalide in particular bring interesting new dimensions to their roles.

An advantage of being in a small theater was that we were able to see the real tears wept by both Hétier and Godet; it was hard not to be similarly moved by the end.

The Théâtre du Nord-Ouest clearly operates on a minimal budget, but its productions are often of much higher standard than those of its better-known counterparts. Rush to see Bajazet if you can. It may be a long time before another excellent production of the piece comes along.

Favorite