The Fondation Cartier has done Parisians a favor by organizing the vibrant exhibition “Beauté Congo,” a survey of nearly a century of painting, sculpture, photography and music in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. With a refreshing burst of color and exuberance, the paintings explode from the walls, moving backward in time from the present and near past on the ground floor to the 1920s in the basement.

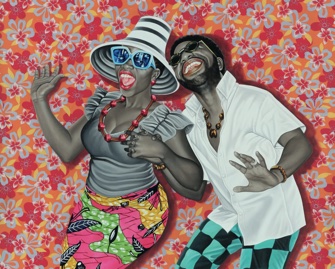

Many of the dynamic large-format paintings on the ground floor are the work of the “peintres populaires,” painters who in the 1970s (a little over a decade after the country’s liberation from Belgian colonial rule), eschewed the European style taught at the Kinshasa Academy of Fine Arts and instead opted for colloquial subject matter, bright colors and bold execution. They started out doing illustrations for advertising and making comic books – whose playful influence is evident in their work – and made their names by hanging their paintings on the outside walls of their studios to stage open-air exhibitions.

One of the best-known and most influential of these artists is Chéri Samba, whose works – like those of many of the others – have overtly political massages treated with humor and derision. In “Little Kadogo – I Am for Peace, That Is Why I Like Weapons” (2004), for example, a heavily armed small boy, dressed in fatigues and standing in a cheery, flower-filled setting against a bright blue sky, raises his hands in the air while staring menacingly at the viewer. While Samba’s works, with their written messages, can sometimes be a bit preachy, they are always saved by their satirical edge.

Tragically, one of the artists, the 36-year-old Kiripi Katembo, died of malaria not long after visiting Paris for the opening of the show. He is represented by his handsome, carefully composed large-format color photos of life in Kinshasa reflected in the puddles that swamp the city.

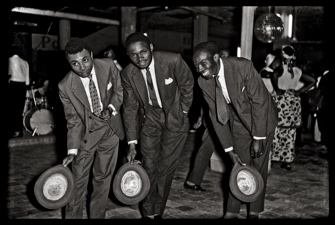

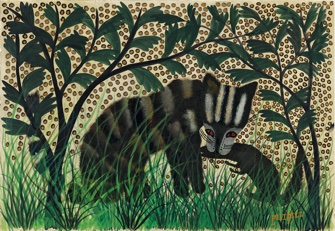

Downstairs, visitors find the magical models of fantasy cities built of found objects by Bodys Isek Kingelez; black-and-white photos of life in Kinshasa from the 1950s and ’60s by various photographers, and some of the first works on paper, from the 1920s, by artists who started out by painting on the walls of their huts and were then “discovered.”

There is also a large collection of joyous, colorful works by artists from the post-World War II Hangar school in Elisabethville, like the one by Pilipili Mulongoy shown above.

As in many of the Fondation Cartier’s exhibitions, the show is not devoted to the visual arts alone, but to more general cultural concerns. Most originally, it offers a number of music stations where visitors can sit down and listen to a few tracks, each one linked with one of the works on show, some with fairly direct connections – such as the pairing of Papa Wemba’s “Matebu” (1982) with “La SAPE” by JP Mika. La SAPE, or the Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Elégantes, was a group of dandies with which Papa Wemba was closely associated. Other songs are more atmospherically linked with artworks.

Visitors who take the time to see all the works of art, listen to all the music and watch all the filmed interviews with the artists as well as a highly enjoyable 1970s documentary about Kinshasa, could happily spend the whole day at the Fondation Cartier taking in this world that seems so far from Paris.

Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain: 261, boulevard Raspail, 75014 Paris. Métro: Raspail. Tel.: 01 42 18 56 50. Open Tuesday, 11 a.m.-10 p.m.; Wednesday-Sunday, 11 a.m.-8 p.m. Admission: €10.50. Guided tours at 6pm. Through January 10, 2016. fondation.cartier.com

© 2015 Paris Update

Favorite