New York’s Museum of Modern Art has not been moved lock, stock and brushes to Paris, but it may seem that way when you visit the exhibition “Being Modern: MoMA in Paris,” at the Fondation Louis Vuitton through April 18.

The show walks us through the museum’s entire history, from its founding in 1929 to its latest acquisitions, with 200 works from the museum’s collection, along with numerous documents and texts on the history of the museum itself.

The story of modern art begins here with works dating from the 1880s, most of them European – Cézanne, Picasso, Brancusi, Signac, etc. (many of them have never before been shown in Paris) – although there is the occasional work by an American, e.g., Edward Hopper’s eerie painting of the prototypical haunted house, “House by the Railroad” (1925), which was the first important painting to enter the museum’s collection.

The museum did not stick to the beaten path, however, but accepted design, architecture, film and photography into its collection at a time when they were still often sniffed at as minor art forms. Its director at the time, Alfred H. Barr, Jr., can be credited with this daring approach. Barr was also responsible for groundbreaking exhibitions of the work of Vincent Van Gogh and Pablo Picasso, which permanently opened the hearts and minds of Americans to these artists.

The extensive sections in the exhibition on the museum’s history look rather intimidating, but contain some gems, including a complex diagram, drawn by Barr for the cover of the book Cubism and Abstract Art, showing the links between modern art movements; a photo of Albert Einstein at the 1939-40 retrospective of Picasso’s work; and a signed, silkscreened tie and hand-decorated envelope sent by Picasso to Barr in 1957.

Strangely, Barr, who was fired in 1943 as director but kept on in a lesser capacity until 1968, never really took to Abstract Expressionism, the movement that stole the modern art limelight from Europe and for which MoMa’s collection is best known today.

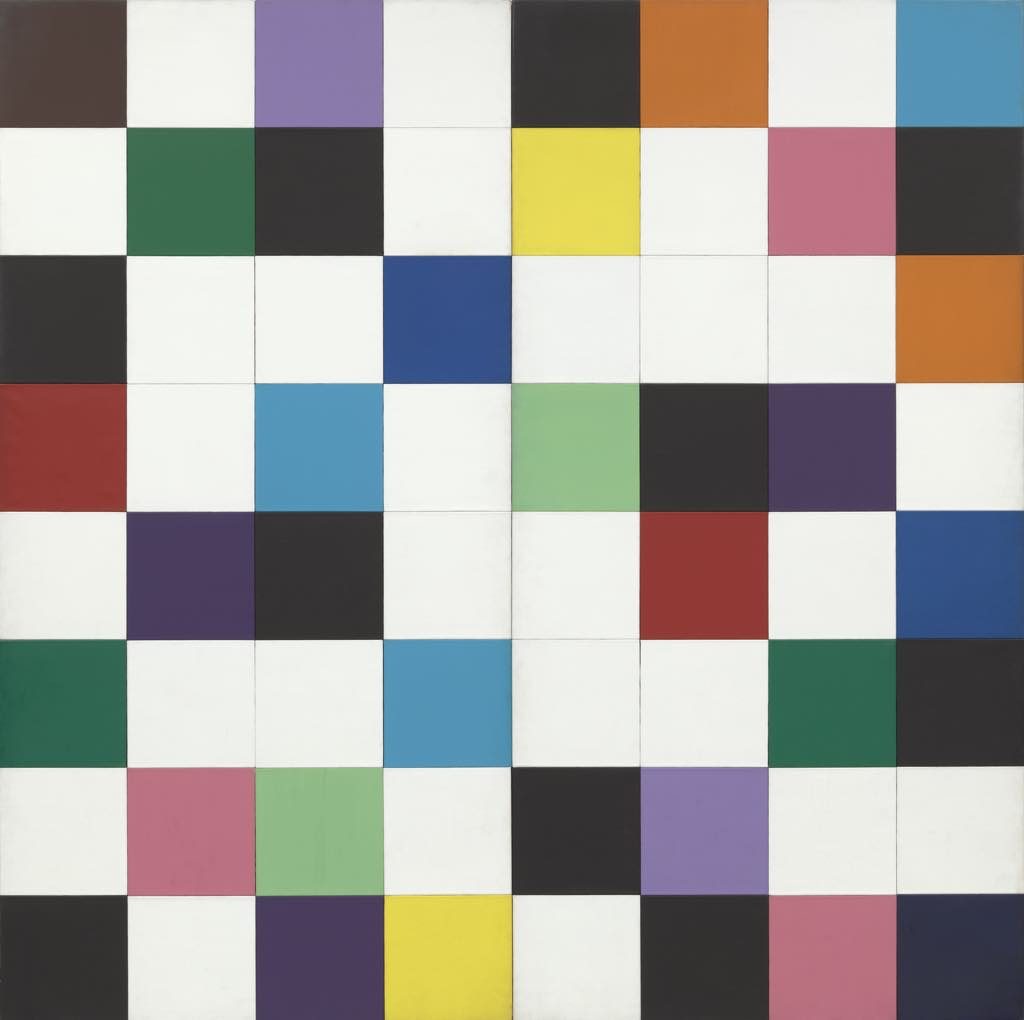

We don’t get the best of the New York School here, but we do get a beautiful Mark Rothko (Barr never purchased a single work by him) painting, “No. 10” (1950) and Barnett Newman’s “Onement III” (1949). Ellsworth Kelly’s “Colors for a Large Wall” (1951) represents the Color Field movement.

Representing Pop Art, we have a Roy Lichtenstein painting and Andy Warhol’s hand-painted “Campbell’s Soup Cans” (1962), all 32 varieties, and his wonderful “Screen Test” (1964-66), films of celebrities and friends staring into a camera for four minutes with nothing else to do. Bob Dylan tries to pretend the camera is not there as he smokes a cigarette, while Salvador Dalí hams it up.

Don’t miss the series of snapshots and Polaroids by unknown photographers, many of which show an innate talent for choosing a subject and framing an image.

The show goes on chronologically, touching on almost every form: video art, conceptual art, installation art, digital art (complete with playable versions of Space Invaders from 1978), etc.

Don’t miss the very last piece in the exhibition: Janet Cardiff’s “The Forty-part Motet,” in which each of 40 speakers represents one child’s voice from the Salisbury Cathedral Choir singing the complex polyphonic harmonies of “Spem in Alium Nunquam Habui” (“Hope in Any Other Have I None”), a 16th-century composition by Thomas Tallis. After listening to the entrancing 14-minute piece, you will leave with your head in the clouds, which you will, in fact, be able to see through Frank Gehry’s sculptural glass building, the home of the Louis Vuitton Foundation.

Favorite

Absolutely, do not miss the motet, astoundingly beautiful.