I heard it over and over again whenever I mentioned the Bernard Buffet (1928-99) retrospective at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris to a friend or acquaintance: “I don’t like him. I’m not going.” From what little I knew of his work – a painting glimpsed here and there – I didn’t like him either, but I was curious to find out what it was all about.

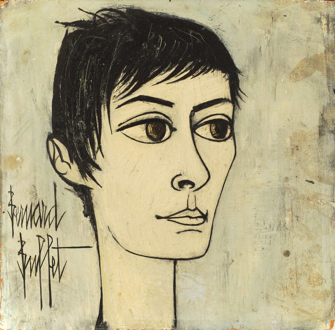

I was surprised at how affecting the bleak paintings in the first few rooms were. These works from the artist’s early years, when he was still in his late teens and early 20s, are pure Buffet (or what we think of as pure Buffet). His unique style is instantly recognizable, with stiff, angular figures and lonely objects, crisscrossed with spindly lines, painted in thin layers of dull, pale shades of gray and brown, apparently because of the difficulty of finding colors in postwar France.

They are haunting in the way that an Edward Hopper painting is haunting, with a deep feeling of emptiness and alienation in spite of their mostly anodyne subject matter. The figures never look at the viewer, just stare blankly into space, with nary a spark of light in their eyes. Buffet’s self-portraits are hardly flattering either, always showing his snaggly teeth bared in a snarl.

This angst seems wholly appropriate so soon after World War II but also piques one’s curiosity about the artist’s biography and psychology. How could such a young man produce such grim images? The answer may lie in the fact that not only had he lived his youth through the war years, but had also found his mother, who had raised him alone, lying dead in the garden in 1945, a loss that apparently marked him deeply.

Nevertheless, Buffet quickly went on to become the chou-chou of the French art world, riding high on his fame and the wealth it brought him. The public saw him as the heir to Picasso, and the critics honored him with the Prix de la Critique in 1948, when he was only 19. He was hanging out with the glitterati of the day – including Françoise Sagan, Brigitte Bardot and Jean Cocteau – and was living with culture entrepreneur Pierre Bergé.

The dream began to fall apart in 1956 when Paris Match published photos of him with his Rolls-Royce and his country château. Around the same time, the critics started taking a grimmer view toward his work, mocking its “misérabilisme.” The public continued to admire him, however, until he shocked them with the series “Oiseaux” in 1959, which depicted gigantic birds hovering over a naked woman (his wife Annabel), her legs spread wide, his version of the Leda and the Swan myth.

While the early paintings are certainly not uplifting, they are fascinating and even likable in spite of their strangeness. Later, though, his works become more cartoonish and strident and lose their appeal.

We can’t blame the artist for wanting to move on (and he certainly would have been criticized if he kept repeating himself), but, try as I would, I did not feel drawn to the tragic clowns, the flayed humans in his “Écorchés” series and the terrifying prostitutes in the “Femmes au Salon” paintings (1970). They scream horror rather than speaking it quietly as in the near-monochrome works of his early years.

Some of the later paintings called out to me more than others, among them the animals and insects (Buffet was a great nature lover), the Courbet-influenced still lifes and a few monumental pieces like “L’Homme à la Tête Coupée” from the “Dante’s Hell” series, and the anti-war “Horror of War, Angel of Death.”

I was also moved by the final group of paintings, “Death,” made when Buffet was having difficulty working because of Parkinson’s disease, shortly before he committed suicide in 1999. A short film made by his son shows him painting these works (reminiscent of Jean-Michel Basqiat’s macabre

figures), with their skeletons dressed up in Renaissance costumes. Buffet had originally painted the figures as living beings and then removed the flesh to reveal their skeletons. Attended by menacing birds, they seem to laugh defiantly at our fear of death.

That the exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art doesn’t tell the whole story about Buffet becomes obvious if you pay a visit to the show, “Bernard Buffet: An Intimate Portrait” at the Musée de Montmartre, which includes very few of the haunting early works, but a number of the kind of pretty pictures one wouldn’t expect from an important artist, some of which – such as the picturesque “Village in the Snow” (1975) – almost fall into the category of kitsch.

There are some powerful paintings here as well, however, such as “Saint Sarah ” (1965), a hieratic portrait that, like the “Death” series mentioned above, resembles a tarot card, and many appealing still lifes, cityscapes and graphic works. In a series of lithographs, Buffet – who was born on the nearby Place Pigalle and frequented the Cirque Médrano as a child

(as an adult, he lived down the street from the Montmartre Museum for 10 years) – offers amusing portraits in words and pictures of different circus performers and animals, reserving his highest respect for the animals: “Humans are ridiculous,” he writes on one, “Animals, never!”

Annabel, the beautiful model and writer Buffet married in 1958, not long after he separated

from Pierre Bergé, looms large in the Montmartre exhibition. She was his muse and the love of his life, and apparently regretted that he didn’t take her with him when he left this life for good.

Whatever one thinks of Buffet, he is back in business (one painting sold at auction for over a million dollars this year), especially after these two reputation-rehabilitating exhibitions, just another episode in France’s love-hate relationship with the artist. I am happy to have learned about him, but I must admit that, like the critics who disparaged his later works, I prefer the spare paintings of the 1940s and ’50s. Still, one has to admire Buffet as a serious, hard-working painter who wasn’t afraid to go his own way, staunchly continuing to paint figuratively in the age of abstraction and pressing on in spite of his critics.

Musée de Montmartre: 12, rue Cortot 75018 Paris. Métro: Lamarck-Caulaincourt or Abbesses. Tel.: 01 49 25 89 39. Open daily, 10 AM-6 PM. Admission: €11. Through March 5, 2017. www.museedemontmartre.fr

Favorite