Napoleon Bonaparte is one of history’s endlessly fascinating characters. Never forgotten, especially in France, he is getting an extra dose of attention this year, the 200th anniversary of his second abdication as emperor of France and forced departure for exile on the faraway island of Saint Helena.

“Destination America: Napoleon’s Last Utopia,” an unusual exhibition being held at Malmaison, just outside Paris, touches on a little-known aspect of Napoleon’s career: his plan to emigrate to the United States after he had been defeated at Waterloo on June 18, 1815, and abdicated on June 21. On the 25th, he took refuge at Malmaison (with his entourage and a guard of 300 soldiers), a country house he had shared with his first wife, Josephine, the great love of his life, and where she had died in 1814, five years after their

divorce. Napoleon spent five days there, and just before leaving on June 29, secluded himself for a time in the bedroom where Josephine had expired.

Obsessed with the idea of starting over in the New World, he spent most of his time at Malmaison preparing for his departure. Two

frigates were ordered to await him in the port of Rochefort, and he dispatched emissaries to his former imperial palaces (technically no longer his property) to gather certain objects he wanted to take with him: a mixture of personal souvenirs like portraits of Josephine and his son, the four-year-old King of Rome; practical items like clothing, camp beds, rifles, scientific instruments, and maps of and books about North America; and majestic pieces like sets of fine porcelain dinnerware and all the silver from the Tuileries and Elysées Palaces.

A number of these objects, many of which eventually accompanied him to Saint Helena, are on display in the exhibition, including Napoleon’s pajamas (with feet!), slippers and bathrobe. Other personal items include his straw gardening hat, a small glass box still containing a few pieces of his licorice, and a couple of nécessaires, handsome cases filled with toilet articles cunningly fitted together.

Scientific instruments were also included, since Napoleon planned to head up scientific explorations of the New World. He also packed up his legend in the form of paintings of his battlefield triumphs. A map discovered while the exhibition was being prepared shows that after the event, Napoleon was still refighting the battle of Waterloo on paper.

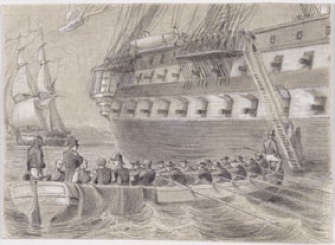

The exhibition documents “a non-event, a plan, an unrealized dream.” Instead of leaving incognito in the night – an idea that was proposed to him and which might well have worked – Napoleon insisted on leaving in the style befitting the emperor he still considered himself to be, ignoring the fact that the British blockade of the port made the departure of his frigates impossible.

One can’t help but wonder what might have happened had Napoleon actually made it to the United States. Would he have marked its history further (he had already helped the country expand by selling the Louisiana territory to the United States in 1803 after regaining control of it from Spain in 1800)? Some of his followers did manage to establish themselves in America, including his brother Joseph, who lived the life of a gentleman farmer near Philadelphia, and some of his generals and soldiers, who tried to set up colonies in Alabama and Texas.

The English had other plans for him: on July 15, they took him into custody and had him shipped off to Saint Helena, a remote speck of an island in the South Atlantic Ocean, where he died in 1821. The last word that passed his lips was “Josephine.”

This interesting exhibition provides a good

excuse to visit Malmaison, a charming country house containing some of the original furniture and many souvenirs of Napoleon and Josephine. Its rose garden, lovingly tended by Josephine during her last years, is a must.

Favorite