Without having read Casanova, I thought I knew him. His name being synonymous with prodigious sexual conquest, I had intended to read his memoirs out of prurient curiosity, but what a revelation when a couple of years ago I actually sat down to read his History of My Life. Not only is Casanova a damn good storyteller, as good as any novelist of his era, but he creates out of his own life what is surely the most vivid picture of the 18th century we have.

The book is full of surprises. As a seducer, Casanova invariably seeks the woman’s pleasure before his own and is never satisfied with simply gaining acquiescence but wants always to inspire passion and desire in the object of his affections; he “loves to be loved.” Predictably, he calls himself a libertine and a hedonist, but then almost startlingly declares, “As for women, I have always found that the one I was in love with smelled good, and the more copious her sweat the sweeter I found it.” The statement has all the pungency of Napoleon’s famous note to Josephine: “Home in three days. Don’t wash.”

Here is a man who thoroughly loves women, and, though he has hundreds of them, is faithful to each one in his fashion. He is in essence serially monogamous, focused at any given time exclusively on the particular woman of his fancy, and it is this hyper-focus, no matter how momentary, that wins them over.

Predictably, many of Casanova’s women want to get married and continue the romance at their leisure, but Casanova likes the intense process of falling in love better than the comfortable continuity of married life, so the History shows our hero wriggling out of more connubial promises and obligations than any man before or since. As a Latin American woman I know once said about Latin lovers: “You know they’re lying, but it feels so good.”

Casanova keeps his reader posted on the state of his finances almost as minutely as on his love affairs, which might not seem a fascinating topic but turns out to be. Europe in Casanova’s time was a hierarchical place in which one’s social status depended on a number of subtly interdependent factors. His parents having been actors, truly a pariah class, Casanova could have been strictly a denizen of the murky lower depths if he hadn’t developed a knack for passing for a man of leisure. That required infusions of money, gained in Casanova’s case mostly by gambling, sharp practice, elaborate scams, posing as a mage or adept, and sometimes just plain clever and creative dealings, all of which required, ironically, tremendous acting skills, which Casanova possessed in spades, making the membranes between classes permeable to him. He always dressed beautifully, had an exquisite social sense and was never at a loss. His ability to pass in all walks of life, high and low, gives Casanova’s portrait of his times its wonderful breadth. Because he comes from the underclass, Casanova doesn’t think it beneath him to describe at close hand the antics of chambermaids and valets, and he’ll tell you of his affair with a kitchen wench as readily as with a duchess.

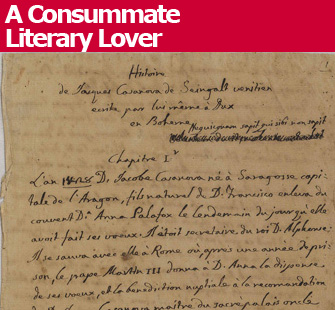

Beyond the personal and historical interest of his book, Casanova has extraordinary literary abilities. He tells his long tale swiftly, with the breathless, headlong, full-tilt sparkle of Voltaire’s much shorter Candide. He never seems to nod or tire, which is unusual in any epic-length book but especially one written by an elderly man. Occasionally we get glimpses of our narrator, now an old man writing after the French Revolution, furiously scribbling out his memoirs as a way to recapture his past, but he doesn’t seem to be settling scores or telling tall tales of his glory days. Often his stories don’t reflect well on him, but, driven by a strong confessional impulse, he seems always to be telling the reader the unvarnished truth. He says at one point, “Truth is a talisman whose charms are unfailing…. I believe that a guilty man who dares to admit his guilt to a just judge is more likely to be absolved than an innocent man who equivocates.”

Casanova is the Balzac of autobiography, a man who gave us his whole universe. There is no book quite like it in literature; although there were other famous adventurers in his time, none of them was the literary artist he was, capable of resurrecting an extraordinary life from earliest memory through numerous avatars with apparent effortless vim and verisimilitude. Casanova had a marvelous talent for living and for writing it down, which makes him an autobiographer nonpareil.

Chris Haight

Note: All quotations are from Willard Trask’s wonderful translation of Casanova’s original manuscript (published in hardback by Harcourt, Brace & Jovanovich, 1966-1971, now out of print, and in paperback by The Johns Hopkins University Press) which includes extensive and fascinating notes and illustrations.

Favorite