The magical Musée des Arts and Métiers is one of Paris’s neglected treasures. While hordes of visitors are trying to get a snapshot of Mona at the Louvre, only a handful are marveling at the early flying machines hanging from the ceiling of a former church attached to the museum. Among the many other proofs of human (French) ingenuity are Foucault’s Pendulum, Pascal’s 17th-century calculating machine, a 19th-century steel diving suit and, of more recent manufacture, the original Vélib. Now, human and animal forms have appeared alongside all those mechanical wonders for an exhibition of sculptures by artist-in-residence Cécile Raynal, “Petites Histoires en Réserve,” which are scattered around the museum.

For her residency, Raynal set up her studio and kiln in the museum’s reserves and used the employees as models. She kept notes on their conversations during the sittings, inspired by a question she asked each model about an object that has a personal meaning for him or her. Some of her notes are reproduced in the exhibition, adding another layer of meaning to the sculptures.

Raynal, who has worked in other institutions like prisons and psychiatric facilities in the past, enjoys immersing herself in a particular community and then going back to the individual, whose identity might be lost amid the group, through her sculptures of them.

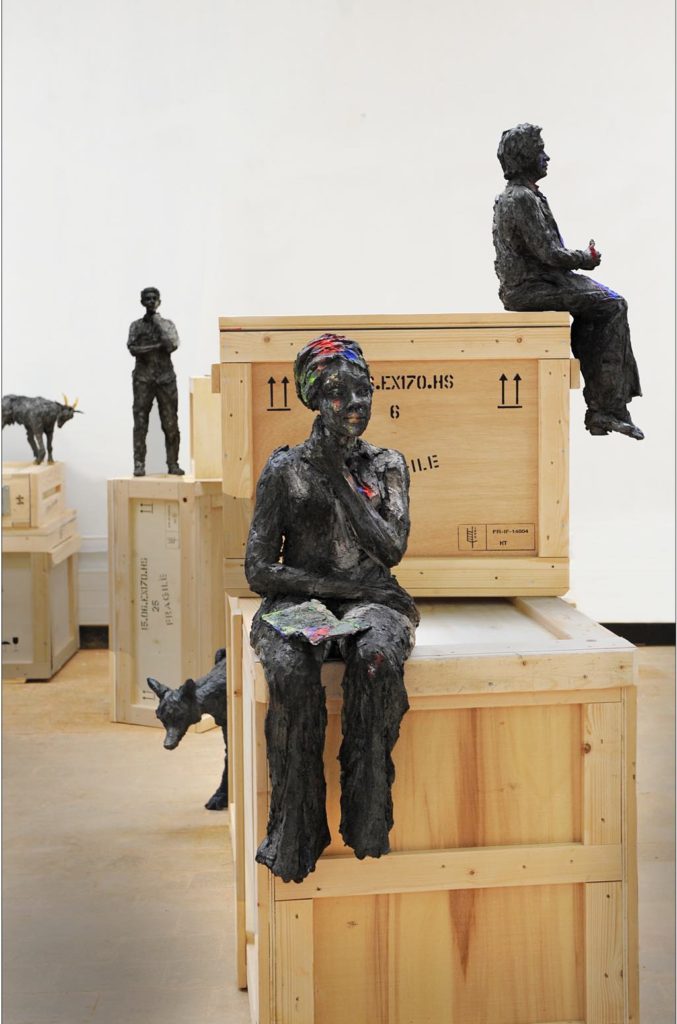

The works are presented as installations combining the sculptures with wooden packing cases from the museum’s reserves with Raynal’s sayings printed on them – e.g., “Caress,” “Don’t lose your head,” “Never despair” – and, occasionally, with objects from the reserves, such as a model of the radium atom.

Raynal plays with scale, sometimes pairing her human figures with woodland creatures like foxes, deer and rabbits. In “Rêve de Longues Oreilles” (“Dream of Long Ears”), for example, a seated man with a rabbit on his shoulder stands next to a rabbit as big as he is (with very long ears indeed) as it leaps out of a glass box.

Raynal has an original technique for creating her sculptures, one that she adapted from the Japanese pottery-making technique of raku. She retained only the part that interested her, smoke firing, which involves firing the clay figures to 1,200 degrees C, cooling them to 1,000 degrees C, then burying the red-hot sculptures in a combustible material like sawdust and leaving them to smoke for two or three hours.

The result is a surface with a burnt, metallic or ashy appearance. A film in the exhibition and on the museum’s website pictures this interesting process, in which sparks flying around the glowing sculptures seem to be working magic on the corpse-life figures and bringing them back to life.

Raynal, a former dancer, took up sculpture after a sojourn in Africa, opting for figuration because she wanted to “enter a face the same way you would enter a landscape.” Her experience as a dancer seems to have given her an intimate knowledge of the human body and may also be a source of the enigmatic poetry of her installations, which have a dreamlike feel to them with their unreal dimensions and animal companions. As writer Nancy Huston, who wrote the preface to a new book on Raynal’s work, Mémoires de Braise (Privat), puts it, “Cécile Raynal the dancer gave up on evanescence, or rather, she chose to capture in clay the evanescence of everything, every gesture, every act.”

Favorite

Fabulous…I find no other words to describe this great art…

What a deep and sensitive description of the artist’s work ! Cécile Raynal who always leads us farther allies a moving maturity and a profound humanity to an acute control of his art.