Philosopher-Painter

Resurrected from Oblivion

“Evening, or Lost Illusions” (1843). Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée du Louvre) /Michel Urtado

Don’t be ashamed if you have never heard of Charles Gleyre (1806-74), the subject of an exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay. Few have, and this is the first retrospective of “The Reformed Romantic” (the show’s subtitle) to be held inFrance.

There was a time, however, when the Swiss-born Gleyre, who spent most of his life in France, was well-known to the French public. For an entire century, one of his works, the atmospheric “Evening, or Lost Illusions” (1843) was a must-see in the Louvre and was widely reproduced as a print. It was even mentioned in A la Recherche du Temps Perdu by Marcel Proust, who described the new moon in the painting as “clearly cutting out a silver sickle in the sky.”

The moody allegoric painting was the struggling artist’s first real success, a gold-medal winner at the Salon in 1843, when he was already 37 years old. Based on a hallucination he had experienced on the banks of the Nile during his travels in Egypt, it shows a poet sitting dejected on the shore, his lyre fallen to the ground beside him and a delicate sliver of a moon hanging above his head as a boatload of music-making young women moves away from him.

During a life that seems to have been marked by many difficulties and illnesses, Gleyre, a bachelor and a fervent Republican, became a master to a number of artists whose names lived on while his was forgotten, among them James Whistler and a group of rebellious students who moved on to the new horizons of Impressionism: Alfred Sisley, Frédéric Bazille and Auguste Renoir. Claude Monet, too, spent some time in Gleyre’s studio, but soon left, finding the older artist’s sensibility and approach too different from his. The spontaneity of Impressionist paintings is indeed light-years away from the long-gestated and carefully prepared works by Gleyre.

While Gleyre’s paintings may have already seemed outdated to many of his students and still have an archaic feel to them today, his talent is impressive and his works have an originality that is difficult to discern today without the guidance of a show like this. His early work “The Roman Brigands,” for example, is unusual in that it shows the true colors of these thieves – the partially undressed young woman sobbing on the ground has obviously just been raped by the bandits, while her frantic husband is tied to a tree – rather than romanticizing them the way popular paintings of the day did.

In 1845, art critic Théophile Gautier summed up Gleyre well as a “philosopher-painter,” adding, “His talent is serious and thoughtful, sometimes to the point of coldness and sadness, leaving little to chance in the execution and taking from reality only what he needs to express his idea.”

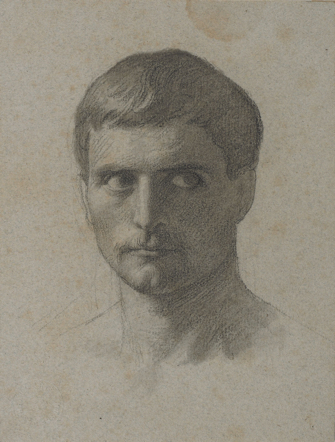

Enormous planning must have gone into a complex painting like “The Romans Passing Under the Yoke” (1858), with its dozens of highly animated figures. A close look at the faces of the humiliated Roman prisoners (they had just been defeated by a Helvetian tribe they were trying to drive away from the shores of Lake Geneva) in the center shows Gleyre’s wonderful mastery of their images and expressions. A pencil study of one of those

“Study for The Romans Passing under the Yoke” (1854-58), © Nora Rupp, Musée Cantonal des Beaux-Arts de Lausanne

faces is particularly beautiful, as are most of the artist’s many drawings on show here.

Other works of interest are the fanciful “The Great Flood” (1856), in which three Giotto-esque angels fly stiffly over a devastated landscape after the waters of the flood have withdrawn, with Noah’s Ark perched precariously on some boulders in the

“The Great Flood” (1856). © Clémentine Bossard, Musée Cantonal des Beaux-Arts de Lausannebackground (Pierre Puvis de Chavannes seems to have used Gleyre’s painting as the model for his 1883 work, “Le Rêve”, also on show here), and “Pentheus Hunted by the Maenads” (1864), in which the nearly naked King of Thebes runs in terror through a desolate landscape, chased by the armed Maenads – some flying, some running – who want to rip him limb from limb.

As he got older, Gleyre began to paint less complex pictures and to move away from historical and mythological subjects. Among

“Femme à sa Toilette” (1859-62) © Nora Rupp, Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts de Lausanne

the later paintings are the lovely “Femme à sa Toilette” (c. 1859-62), a nude female torso, and “Le Bain” (1868), inspired by an Antique terracotta, in which a mother bathes her infant in a basin.

As always, it is a pleasure to discover an artist of the past whose merits have been forgotten. Gleyre may not be to everyone’s taste, but there should be something to please everyone in this show.

Musée d’Orsay: 1, rue de la Légion d’Honneur, 75007 Paris. Métro: Solferino. RER: Musée d’Orsay. Tel.: 01 40 49 48 14. Open Tuesday-Sunday, 9:30 a.m.-6 p.m., until 9:45 p.m. on Thursday. Closed Monday. Admission: €12. Through September 11, 2016. www.musee-orsay.fr

Reader reaction: Click here to respond to this article (your response may be published on this page and is subject to editing).

More reviews of Paris art shows.

© 2016 Paris Update

Favorite