|

|

|

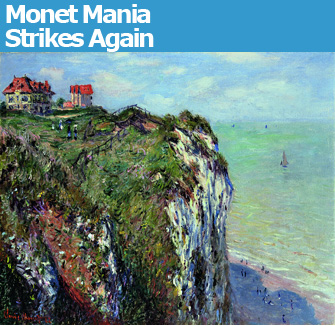

Monet’s“La Falaise à Dieppe” (1882

|

Monet mania is back. Just when you thought you had seen as many water lilies, red poppies and sunrises over the Thames as you ever wanted to see, it is time for …

|

| Monet’s“La Falaise à Dieppe” (1882 |

Monet mania is back. Just when you thought you had seen as many water lilies, red poppies and sunrises over the Thames as you ever wanted to see, it is time for a revival. The retrospective “Claude Monet,” the blockbuster of Paris’s fall art season, opens today at the Grand Palais, and while it holds few surprises, it provides a pleasant reminder of Monet’s often-forgotten versatility and of how his work helped change our way of seeing the world.

When you leave the exhibition, for example, you won’t see the mass of brown chestnut leaves on the trees in front of the Grand Palais exit as just a bunch of dried-up vegetation but as many points of light that could have been painted by Monet. And when I took a train through Picardy yesterday right after seeing the show, the landscapes framed by the window seemed to glow with Monetian light.

So for those who scoff at the decorative prettiness of Monet’s work – like Renoir, he was not ashamed to say that he wanted to create decorative paintings – be aware that there is much more to the Monet story than that. The show begins with paintings made in the forest of Fontainebleau, a favorite subject of the 19th-century French school. Here the young Monet showed that light was already his subject and landscape his forte.

Hungering for success and acceptance by the official Salon, he also painted a monumental “Dejeuner sur l’Herbe,” but wasn’t pleased with it and never showed it. Two surviving fragments of this piece, along with a smaller complete version owned by a Russian Museum, give a glimpse of what it was all about. There are also a couple of Renoir-sweet paintings of the working-class resort La Grenouillère; it turns out that they were actually painted in the company of Renoir.

One lovely painting follows another – many beautiful landscapes, of course, but also intimate scenes in the home and even a few classical still lifes (notice the beautifully rendered hunting dog in the lower left-hand corner of “Trophée de Chasse” [1862], and the two marvelous paintings of bouquets of chrysanthemums), as well as Monet’s wonderful studies of the interiors of

|

|

“La Gare Saint-Lazare à l’Extérieur (Le Signal)” 1877. © Niedersächsisches Landesmuseum, Hanover |

train stations with clouds of billowing smoke. There are also a number of paintings made when Monet was living on the Côte d’Azur, not a place he is usually associated with, where he was rather overwhelmed by the light. “We swim in the blue air. It’s alarming,” he wrote in a letter from the Riviera, adding that he would “need a palette of diamonds and gems” to paint it.

All this is very pleasing and enjoyable, but the most stunning moment occurs when you descend the steps to the lower level of the show and see the dazzling haystack series. Out of these humble piles of hay, which Monet painted over and over again in different light and seasons, he created some of his most brilliant works. They are accompanied by another beautiful series, of a line of poplar trees, and followed by the famous studies of Rouen Cathedral.

While the show presents 169 paintings, that must be just a small sampling of what this prolific, hard-working artist produced in his long life (1840-1926). There are many moments when you want to see more, notably of the paintings of Venice. Monet didn’t visit the city until he was 68, even though it seems a natural match for him: a place with spectacular light where stone meets water, although in less natural conditions than the cliffs of Normandy he painted so often earlier in his career. He painted his views of Venice from water level, sitting in a gondola.

Another missing factor is the famous “Impression, Sunrise,” which the Musée Marmottan, located not far from the Grand Palais, refused to lend to this show. That is a shame, since it would have been a treat to see it alongside the similar views of a red sun over water painted in London (another place whose lighting effects fascinated Monet): “Charing Cross Bridge, Brouillard sur la Tamise” and “Waterloo Bridge, Soleil dans le Brouillard,” both painted in 1903.

The show ends, as Monet’s life did, with paintings of the water lilies in his Giverny garden. For the ultimate water lily experience, however, Monet lovers must go to the Musée de l’Orangerie, where eight monumental water-lily paintings are installed in special oval rooms designed for them by Monet and beautifully lit by skylights. A trip to the Musée Marmottan is also in order to see its fine collection of Monets and other Impressionists.

Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais: 3, avenue du Général Eisenhower, 75008 Paris. Métro: Champs-Elysées Clemenceau. Tel.: 01 44 13 17 17. Open Wednesday, 10am-10pm; Thursday-Monday, 10am-8pm. Admission: €12. Through January 24, 2010. www.rmn.fr

Musée de l’Orangerie: Jardin des Tuileries, 75001 Paris. Métro: Concorde. Tel.: 01 44 77 80 07. Open Wednesday-Monday, 9am-6pm. Admission: €7.50. www.musee-orangerie.fr

Musée Marmottan Monet: 2, rue Louis-Boilly, 75016, Paris. Métro: Muette. Tel.: 01 42 24 07 02. Open Tuesday, 11am-9pm, Wednesday-Saturday, 11am-6pm. Closed Monday. Admission: €9. www.marmottan.com

Order books on Claude Monet from Paris Update’s Amazon store at no extra cost. Click on your preferred Amazon location: U.K., France, U.S.

Support Paris Update by ordering books from Paris Update’s Amazon store at no extra cost. Click on your preferred Amazon location: U.K., France, U.S.

Reader Reaction: Click here to respond to this article (your response may be published on this page and is subject to editing).

More reviews of Paris art shows.

© 2010 Paris Update

Favorite