Was Cy Twombly the painter whose work first elicited the comment “My three year old could have done that!”? Probably not, but he is a good candidate. Universally admired, even adulated, by the art world, he seems less popular with ordinary art lovers.

The other day at the Centre Pompidou’s current Twombly retrospective, I struggled to understand exactly why he is considered a genius. First of all, I have to admit that some of his work – notably the paintings with cryptic scratched-out numbers and words – makes me feel stupid (okay, that may well be the case), as if there is something I should understand but don’t, some deep meaning I’m missing out on.

In his use of writing on the canvas, his influence on Jean-Michel Basquiat is clear, but in Basquiat’s work, the seemingly unrelated lists of scrawled words are wry, evocative, poetic, whereas in Twombly’s case they can seem pretentious. I know many of these paintings are inspired by Greek mythology, but does writing “Agamemnon” on a painting automatically make it meaningful?

The show starts with early works that must have made Twombly’s name as the great scribbler, such as “Free Wheeler” and “Criticism,” both painted in 1955.

Later in the same decade, after his return from a second trip to Rome, the paintings – e.g., “Untitled (Lexington)” (1959) – look less like the mad scribblings of a hyperactive three year old. They are filled with enigmatic doodles floating randomly on the surface, which, according to the curators, “emanate a sense of tranquility, of suspended time.”

The scribbles were made with pencil and pastels on a backdrop of ordinary house paint, which, when examined closely, reveals subtle variations in the tonalities and application of the beige and white paint, indications that Twombly was already a painter’s painter.

This painterliness is what reconciled me to Twombly’s work, especially when more color is introduced, to gorgeous and sometimes moving or dramatic effect.

The color can be used ever-so delicately

and subtly, as in “School of Fontainebleau,” (1960) or “Dutch Interior” (1962); erotically, as in the energetic “Empire of Flora” (1961), full of sexual symbols, which was painted when Twombly was living in Rome with his new wife Luisa Tatiana Franchetti; or violently, as in “Nine Discourses on Commodus” (1963),

inspired by the bloody reign of the Roman emperor.

The end of the show features late works that were almost nothing but pure, screaming color, among them “Untitled (Bacchus)” (2005)

.jpg)

and the “Camino Real” series of fluorescent green, yellow and red scribbles.

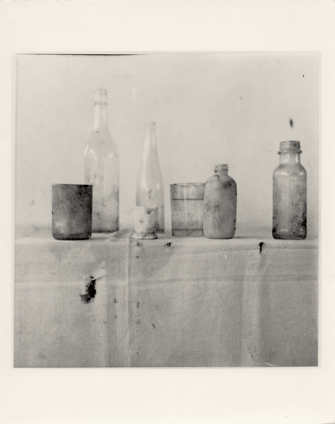

The exhibition also includes some of Twombly’s minimalist photos, among them groups of bottles arranged on shelves, a kind of

photographic ripoff of the work of painter Giorgio Morandi (Twombly was still in college at the time); a rather beautiful and delicate series of collages made with bits of paper and glue, with the glue being used like paint, all called “Speralonga Collage” (1959); and a group of sculptures made of found objects drenched in white plaster, giving them an archaic look.

No matter what you think of Twombly, two things are sure: he knew how to handle paint and color, and he was an original, eschewing the dominant Abstract Expressionism of his early years and, while painting mostly abstract works, never completely renouncing figuration.

Favorite