Inspired by real events that occurred in 1996, when a group of French Cistercian monks was abducted from their monastery in the Atlas Mountains in northern Algeria and held hostage by Islamic militants, Des Hommes et des Dieux (Of Gods and Men) – winner of the Grand Prix at Cannes and prime candidate for a César (although it did not even make the shortlist for an Oscar) – is one of those rare films that has the confidence and integrity to pause and reflect upon issues of conscience, faith and moral values without being sensationalist or superficial.

Much of the movie follows the daily existence of the monks, observing them not only in their routine of prayer and worship, but also at work in the community, giving medical care to the local population, working the land, pouring honey into jars, assisting people in the most mundane of tasks (such as filling in passport application forms for an old woman), and showing an understanding of the beliefs and customs of the locals.

We soon begin to see the extent to which the monks are caught between the rise of violent Islamic radicalism and the anti-Islamist military government, which offers to give the monastery armed protection. At this point, it would be all too easy for director Xavier Beauvois to give a saccharine account of perfect martyrs in the making, but instead we see the monks vigorously debating their choices after a close shave with a band of militants who are refused medication by Christian (played with understated dignity by that fine actor Lambert Wilson), the elected leader of the monks. Some want to return to France, others are determined to stay, and others simply do not know what to do.

The acting is impeccable throughout, and it seems unfair to single out any of the actors, but, in addition to Wilson’s fine performance, Michael Lonsdale gives an extraordinarily humane and human performance as the kindly, aging doctor Luc.

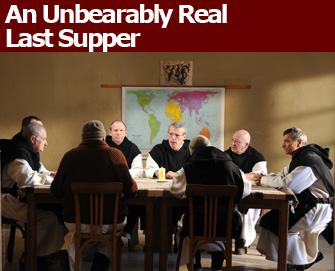

In the film’s most justly celebrated scene, the monks hold a dinner just after the return of one of their brethren from France and after they have made the decision to remain in the monastery. The meal is clearly intended to evoke the Last Supper, but it is also unbearably real. The camera lingers on the lined faces of the monks as they drink wine and listen to a tape-recording of Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake. It would have been so much easier for the director to choose a more openly emotional piece, such as Tchaikovsky’s Symphony no. 6 or a Mahler symphony, but it works perfectly. We see their smiles and then their tears as they realize what lies before them.

There are many beautiful moments in the film, aided by the splendor of the North African mountains, but two shots that frame the film will linger in my memory. At the very beginning, we see the backs of the monks as they process into the church early in the morning, and the last shot shows the monks disappearing into the drifting snow as they are led away by their captors.

The deaths of the monks caused great controversy in France: it is thought that, even though the Islamist militants claimed to have executed them, they were in fact killed during a botched rescue attempt by the Algerian army.

If you have not yet managed to see this magnificent work of art (and it should be called that, as it seems so much more than a movie), I urge you to do so.

Favorite