The depiction of drapery has been a constant in art since Antiquity and is still often present today, although in sometimes surprising forms. The Musée des Beaux-Arts in Lyon has had the excellent idea of devoting an entire exhibition to the subject: “Drapé: Degas, Christo, Michel-Ange, Rodin, Dürer, Man Ray …”

In a wonderful essay I found online, the art historian Andrew Graham-Dixon notes that drapery is so omnipresent in art that it “itself became part of the language of painting: as much of a given, one might say, as any of the parts of speech in written language.” He goes on to say that because it is “so malleable, so open to invention — so inviting of artistic invention, both in color and form …” that it “has always played a vital part in what might be called the secret history of painting.” “Secret” because it is so common that people tend to ignore it.

After a visit to the in-depth and rather overextended exhibition in Lyon, it will be very difficult to ever ignore drapery in art again. The show covers everything from Antique statues to Minimalism and includes sculpture, drawing, painting, photography and video by artists of every stripe.

We learn how artists in the past were schooled in drawing fabric. We learn what the main purpose of fabric in art is: to cover the naked body while suggesting its presence underneath in the fall of the cloth. We see many (too many) examples of the practice of first drawing the model’s body naked then clothed in the same pose when making studies for paintings. In this context, the show includes two marvelous bronze statues of Pierre de Wissant by Auguste Rodin, one completely nude, the other draped in a toga-like garment (one of Rodin’s many studies for Balzac’s dressing gown, sans Balzac, would have fit perfectly into this show).

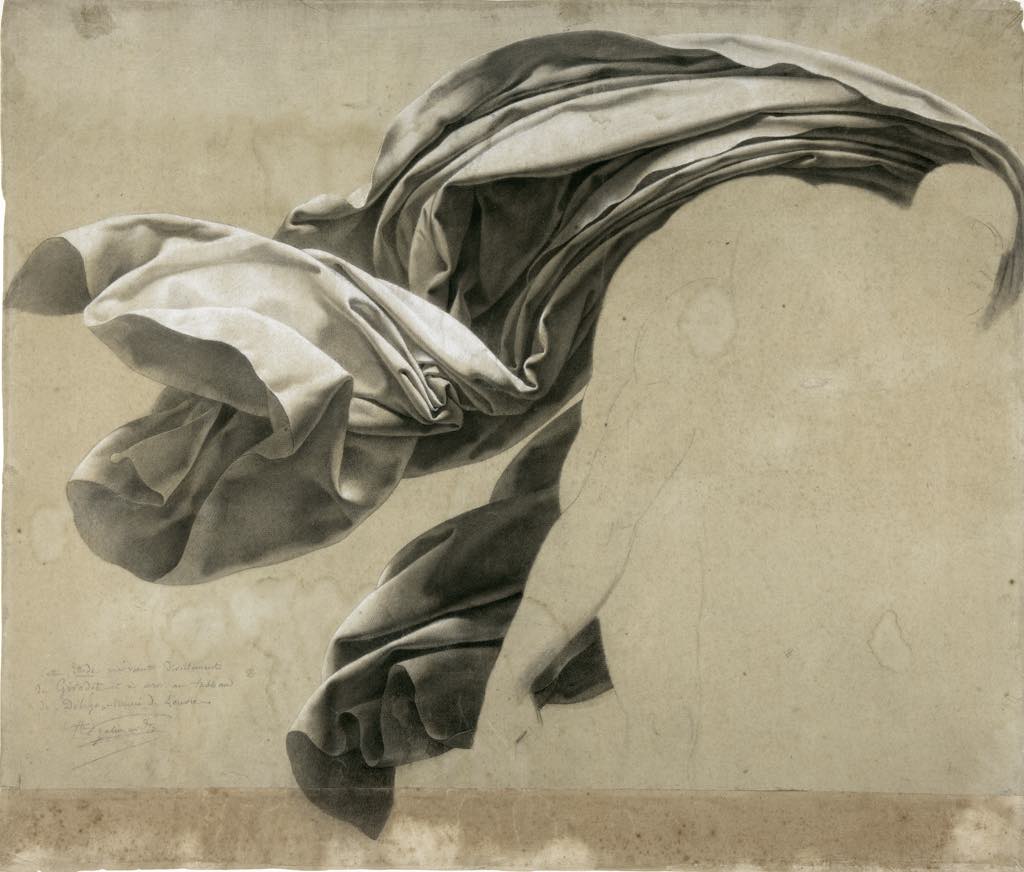

Along the way, we are also treated to many beautiful artworks. Michelangelo’s drapery drawing (1508-09) for a figure for the Sistine Chapel is a shining example.

Jean-Jules-Antoine Lecomte du Nouÿ’s almost photorealistic painting of a draped figure seen from the back (c. 1861-65) is so precise that you can see the finest creases on the fabric. There are also some surprising examples of 20th-century drapery studies, notably the quirky trouser legs or the pair of old gloves drawn by Fernand Léger or the beautiful, almost academic studies by Fluxus and Situationist artist Ernest Pignon-Ernest, who used traditional drawing techniques in non-traditional settings like the streets.

Then there is the astounding early-16th-century engraving by Maître H.L. of Saint Christopher carrying the naked Christ child, who stands in a dynamic position on his shoulders, across a dangerous river. The saint’s head, with his wild curly hair and beard, nearly disappears into a phantasmagorical swirl of drapery. Have a look at this work here.

An entire room is devoted to photographs by Gaëtan Gatian de Clérambault (1872-1934), a French psychiatrist who taught Jacques Lacan and who wanted to create an “anthropology of drapery.” His 1918-19 images of veiled women in Morocco – “living draperies” – show them in movement, sensual, expressive creatures under their all-enveloping robes. Examples of his work can be found here.

While it is full of marvelous pieces, the exhibition is almost too thorough. Rather than trying to be all-encompassing, it would have benefited greatly from a tighter focus on an idea like the one put forward by Graham-Dixon, who thinks that “drapery has often been an escape route for painters, liberating them from reality and the perception that it is their role necessarily to represent the tangible world.” He postulates that these painterly “escapes” were a form of abstraction before its time and that they may have influenced the work of such 20th-century abstractionists as Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko.

Favorite

Wonderful article and curator concept. Tanks.