United by Surrealism,

Divided by Style

“La Belle Saison” (1925), by Max Ernst. Photo: Raphaël Barithel, Geneva. © ADAGP, Paris, 2016

The exhibition “Ernst-Tanguy: Two Visions of Surrealism” at the Musée Paul Valery in Sète, France, demonstrates how, unlike artistic movements that have an identifiable visual style – Impressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, etc. – Surrealism, an intellectually defined approach, is recognizable only by subject matter and can accommodate almost any artistic style. This was made obvious by the glaring differences between the works of Max Ernst and Yves Tanguy, who were friends and fellow travelers in the Surrealist movement.

The German-born Ernst (1891-1976), certainly the better known of the two, must have been a fascinating man, judging only by his many

“Mer et Soleil – Lignes de Navigation” (1925), by Max Ernst. Photo: Raphaël Barithel, Geneva. © ADAGP, Paris, 2016

equally fascinating wives and lovers, among them Meret Oppenheim, Leonora Carrington, Peggy Guggenheim and Dorothea Tanning. He also lived for a time in a menage à trois with poet Paul Éluard and his wife Gala, who later married Salvador Dalí. Ernst moved to Paris in 1922 and spent most of the rest of his life in France, except during and immediately after World War II, which he spent in exile in the United States.

His life as an artist was as rich, varied and colorful as his personal life. A founder of the Dada group in Cologne, Germany, he was a pioneering collage artist, invented the painting techniques frottage and grattage, and

“Fleurs-Arêtes” (1928), by Max Ernst. © Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels. Photo: J. Geleyns – Ro scan © ADAGP, Paris, 2016

experimented with many other techniques. He became interested in dreams and the unconscious in art while a student, long before encountering the Surrealist movement, when he visited psychiatric hospitals and became fascinated by the patients’ artworks.

The works in the exhibition in Sète give the impression of an artist who followed his own dictum: “Painting can and should act on two different and complementary planes: aggression and exultation.” His powerful, highly varied paintings do indeed seem to exult in form and color. Often touched with humor, they become even more exultant as the artist ages, expressing a feeling of real joy later in his life. His “Trente-Trois Fillettes Partant pour

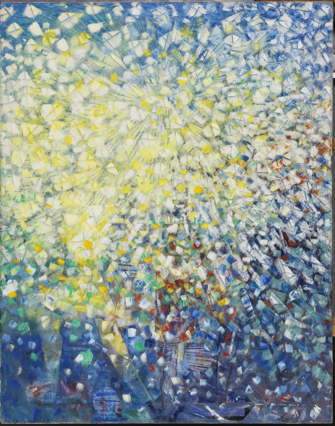

“Thirty-three Little Girls Set Out for the White Butterfly Hunt” (1958), by Max Ernst. © VEGAP, Madrid © Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid © ADAGP, Paris, 2016

La Chasse au Papillon Blanc” (1958), for example, is a joyous fireworks explosion of color.

Tanguy (1900–55) may be better remembered for Man Ray’s famous photo of him, in which he looks like an eccentric imp with a punky hairstyle, than for his paintings. He could be described as the purest of Surrealists: with no training in art, he took up painting after seeing a work by Giorgio de Chirico, and never deviated from Surrealism. He was also one of the few Surrealists who was never kicked out of the movement for offending its founder and theorist André Breton (Ernst was expelled from the club after accepting the grand prize for the Venice Biennial in 1954; prizes were verboten by Breton’s rules).

Tanguy’s motto was: “the element of surprise the creation of a work of art is, in my opinion, the most important factor – surprise for the artist himself as well as for others.”

While his paintings may be surprising when

one first sees them, they tend to repeat the same themes and resemble each other, unlike Ernst’s, which exhibit such great variety of subject matter, color and technique.

Still, there is something fascinating about Tanguy’s idiosyncratic dream world, with its amorphous creatures and unidentifiable forms,

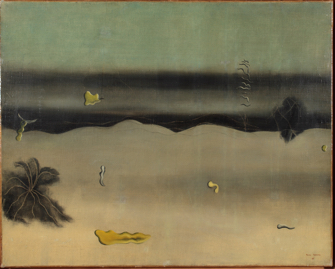

“Untitled” (1926), by Yves Tanguy. Photo: Raphaël Barithel, Geneva © ADAGP, Paris, 2016

which might be drifting underwater or floating in the air. Human figures are completely absent from his paintings, although many of the shapes look like proto-humans.

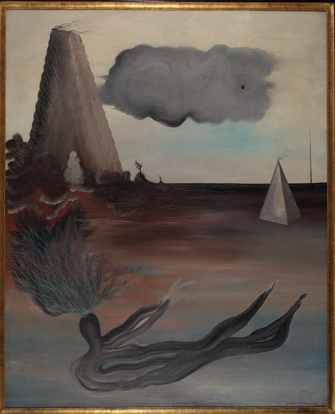

The earlier works in the show are mostly painted in grim shades of gray and exhale a feeling of gloom and doom. Even when color is introduced, it has grayish tones. Later, though, Tanguy’s colors sometimes brighten up. The

“Le Fond de la Tour” (1933), by Yves Tanguy. Photo: Raphaël Barithel, Geneva © ADAGP, Paris, 2016

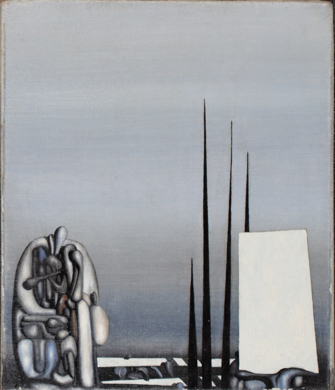

forms start to lose their organic shapes and become more sharp-edged and menacing, with mechanical and architectural shapes that resemble science-fiction worlds. The strange and almost frightening “La Première Clef” (1952), for example, combines a large mass of amorphous gray shapes from which a large spike protrudes, with two wedge shapes, one pure white and the other pure black. We will

“Monde Proche” (1952), by Yves Tanguy. Photo: Raphaël Barithel, Geneva. © ADAGP, Paris, 2016

never know if his approach would have evolved further, since he died suddenly at the age of 55.

This interesting exhibition, in which the vividness and humour of Ernst’s paintings provide the perfect counterbalance to the grimness of Tanguy’s deeply weird yet somehow spellbinding work, also has a section of photos with storytelling captions that conjure up the freewheeling, nonconformist lifestyle of the Surrealists and the antics they got up to together.

The show also offers a fine excuse to visit the charming port town of Sète for a bit of Mediterranean sun.

Musée Paul Valéry: 148; rue François Desnoyer; 34200 Sète. Tel.: 04 99 04 76 16. Through November 6, 2016. Open daily 9:30am-7pm. Admission: €9. www.museepaulvalery-sete.fr

Reader reaction: Click here to respond to this article (your response may be published on this page and is subject to editing).

More reviews of Paris art shows.

© 2016 Paris Update

Favorite