The overarching idea of “Extreme Manuscripts,” the new exhibition at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, is highly original. Instead of showcasing sets of full manuscripts that would go on to form part of the canons of great literature, it concentrates on a wide range of documents that were written in extreme situations, such as at moments of imminent death or in times of mourning, impending madness, or sexual or religious ecstasy. The result is fascinating and in many cases heartbreaking.

Divided into four different themes – Prison, Passion, Peril and Possession – the texts on show date mostly from the early 17th to the late 20th century.

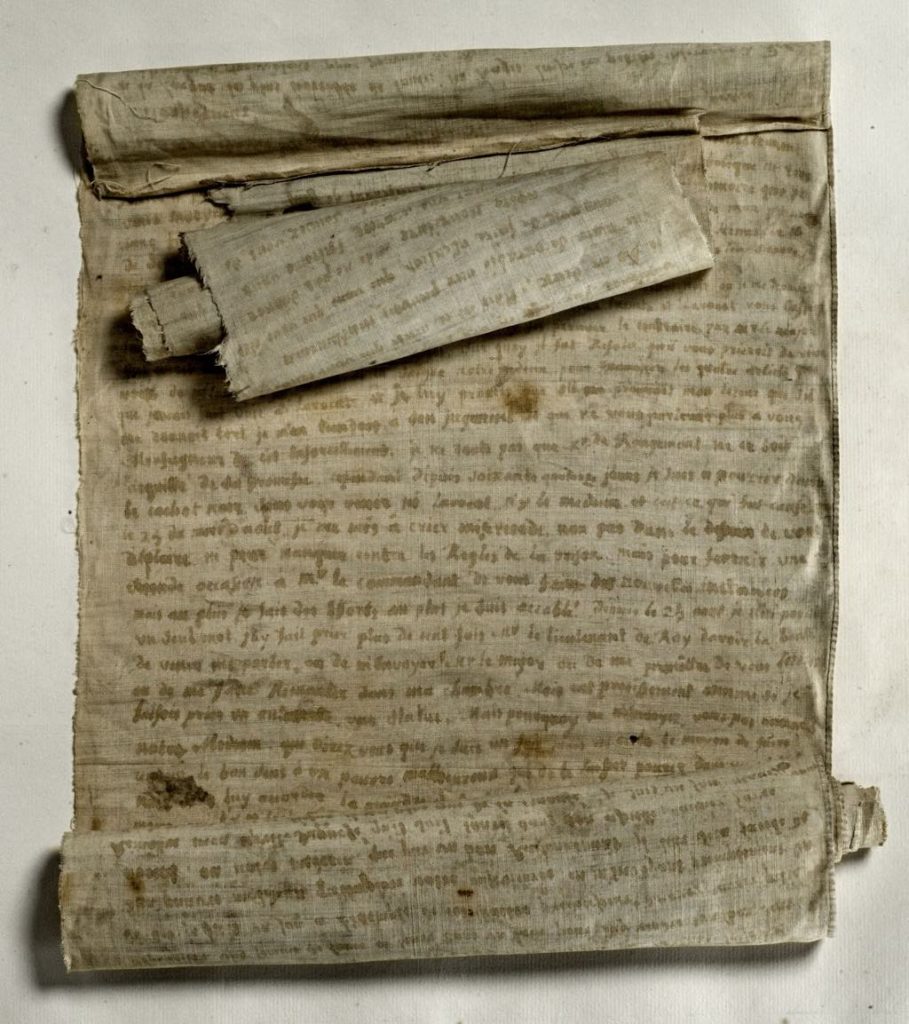

The Prison section is perhaps the most poignant. We find, for example, a letter written in blood on a shirt (because he was denied ink and paper) by the writer Jean Henri Masers de Latude (famous for repeatedly escaping from jail) when he was confined to the Bastille Prison in 1761.

At the time of the French Revolution, the poet André Chénier managed to smuggle some lines of verse for his father out of prison in dirty laundry on the day before he went to the guillotine.

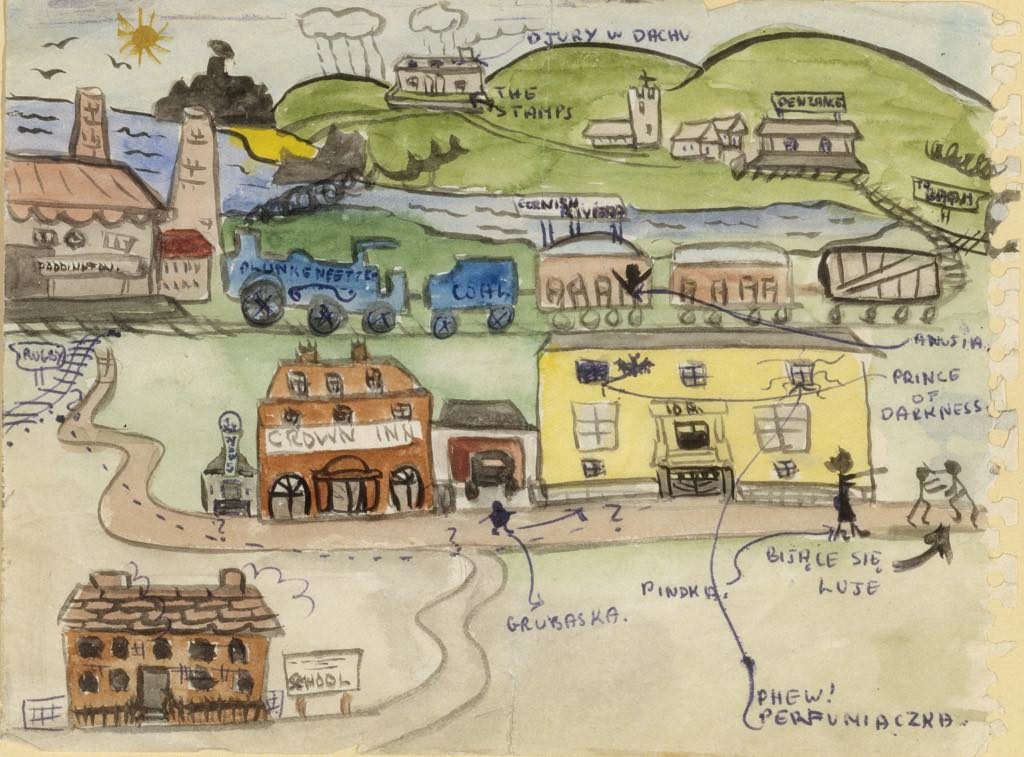

The horrors of the Holocaust and the German occupation of France during World War II play a central role, with a range of different pieces on display. It is almost unbearable to look at the wonderfully creative drawings (see image at top of this page) made by the 44 Jewish refugee children who were hidden in a summer camp in Izieu and who, when discovered, were all deported to their deaths.

The great courage of two sisters, Marie and Suzanne Alizon, who played an active role in the French Resistance, is evident in the scraps of paper with messages to their father that they threw out of the train taking them to Auschwitz (the letters actually reached him; Marie died in the concentration camp, but Suzanne survived).

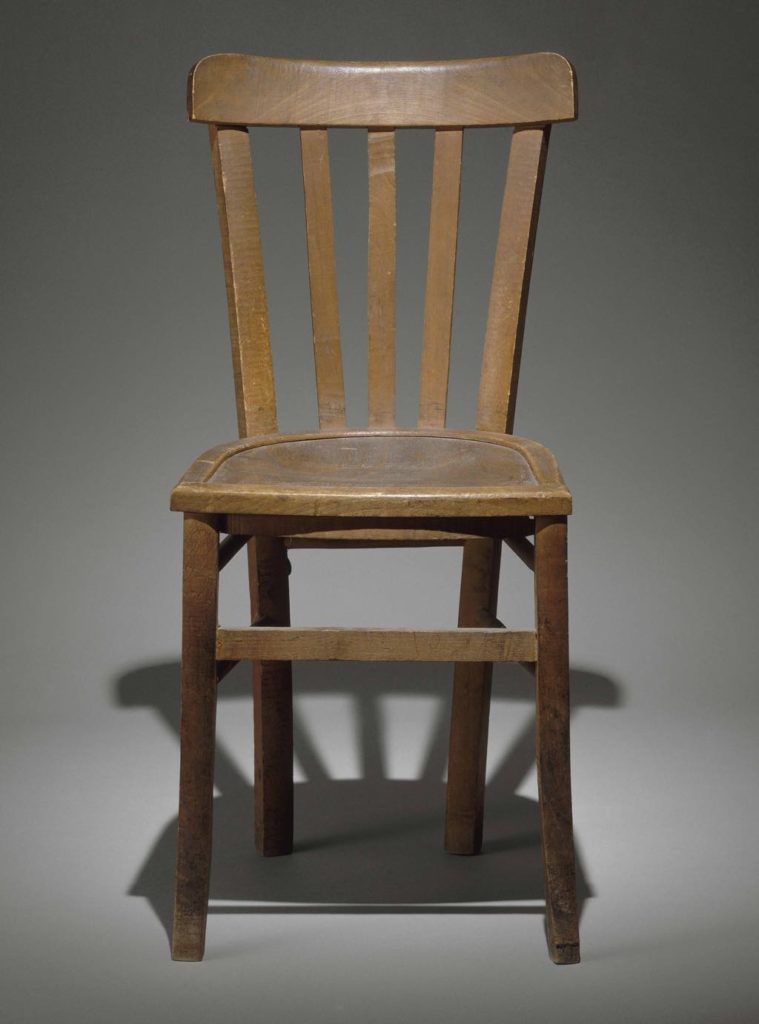

One of the most extraordinary artifacts in the exhibition is a chair found in the Gestapo headquarters in Paris, where a Resistance fighter who was incarcerated and tortured there managed to write a message to his comrades on its underside.

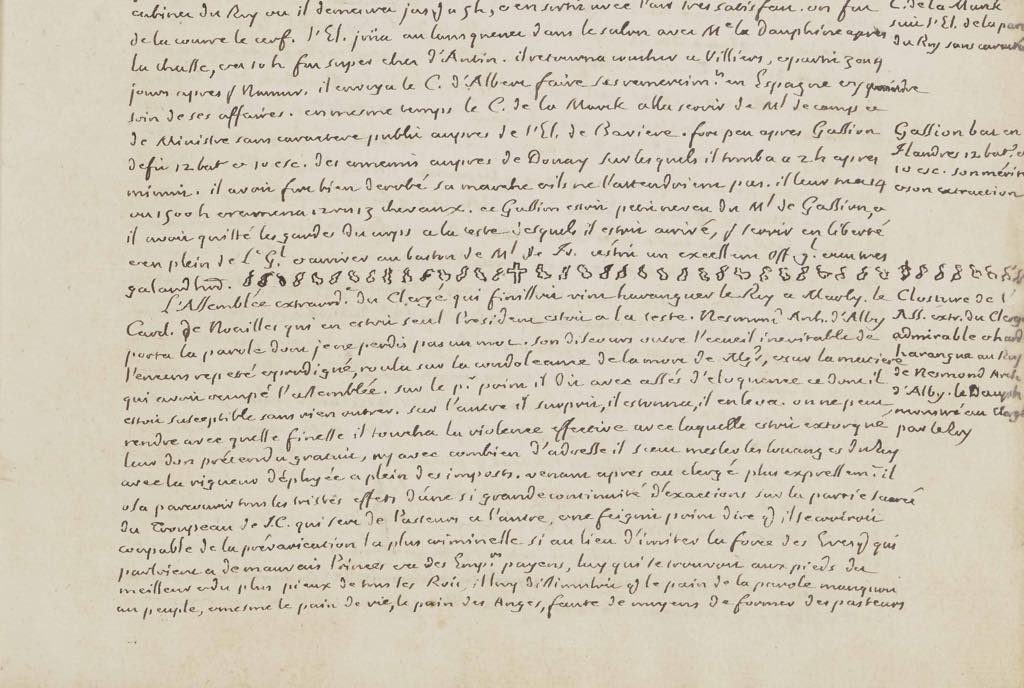

The room devoted to the theme of Passion contains many semi-pornographic written exchanges, some with illustrations, between lovers of every persuasion, but the most affecting documents are those composed by people who had just lost a loved one. The great 18th-century memoir writer Saint-Simon, for example, drew a line of hieroglyphs representing teardrops and crosses in his journal on the day his wife died and stopped writing in it altogether for six months, while the scientist Marie Curie composed a much more heartfelt evocation of the absence that her husband Pierre would leave in her life.

In contrast, Nathalie Sarraute makes a devastatingly simple journal entry in 1985 on the day of her husband’s death: “Il est mort” (He is dead).

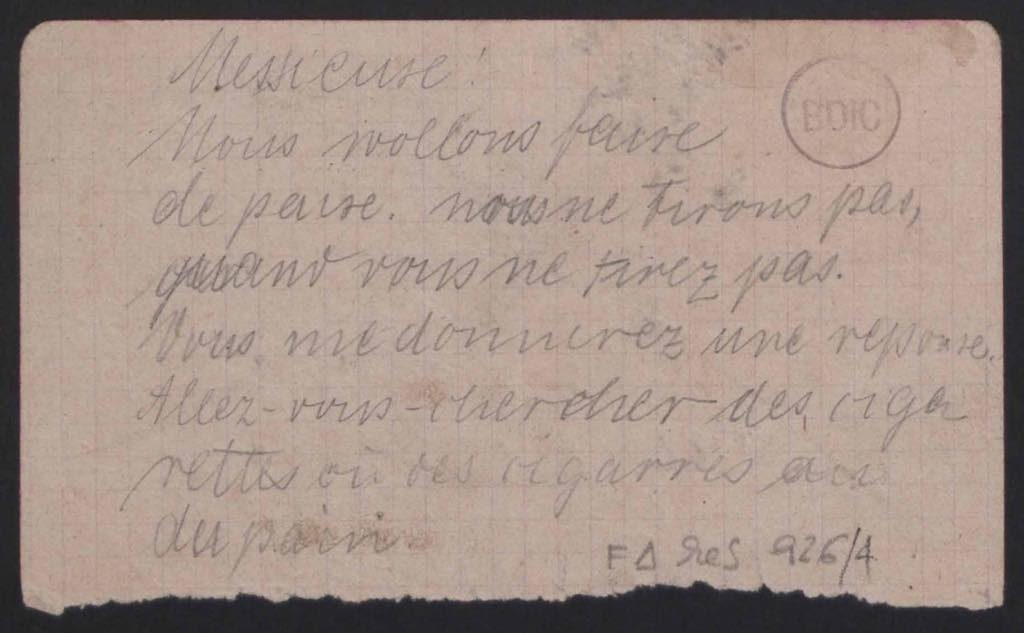

World War I looms large in the section devoted to Peril, with letters or poems sent by men about to die on the Western Front to their loved ones and notes written by German soldiers to their French counterparts on the battlefield asking them to stop shooting and to share their food.

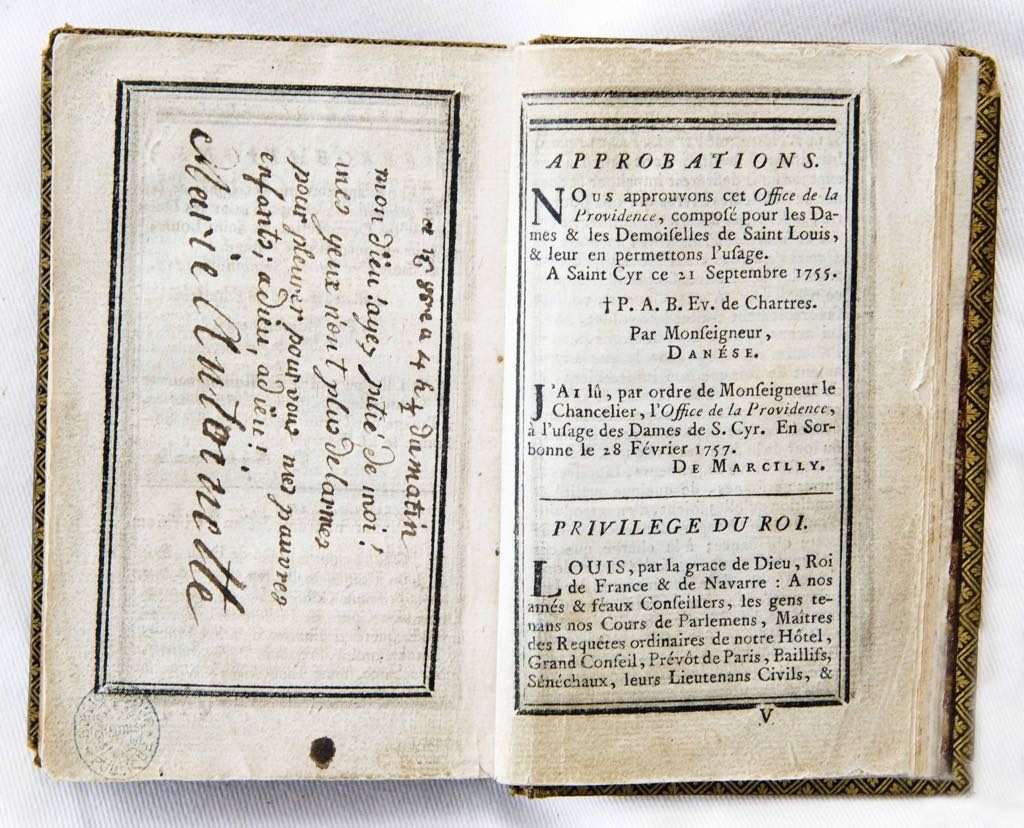

Earlier documents include annotations made Marie-Antoinette on her Book of Hours just before being taken to her execution and a section of Napoleon Bonaparte’s letter of abdication in 1814.

The final theme, Possession, is rather more diffuse, as it deals with all kinds of testimony of religious, spiritual and drug-induced possession. From the 17th century, we have the document known as the Memorial by the philosopher and scientist Blaise Pascal, which detailed his religious conversion during the night of November 23, 1654, and which he sewed into the lining of his coat so it would always be with him. Then there is a document written by the nun Jeanne des Anges at Loudun, supposedly while under the influence of evil spirits.

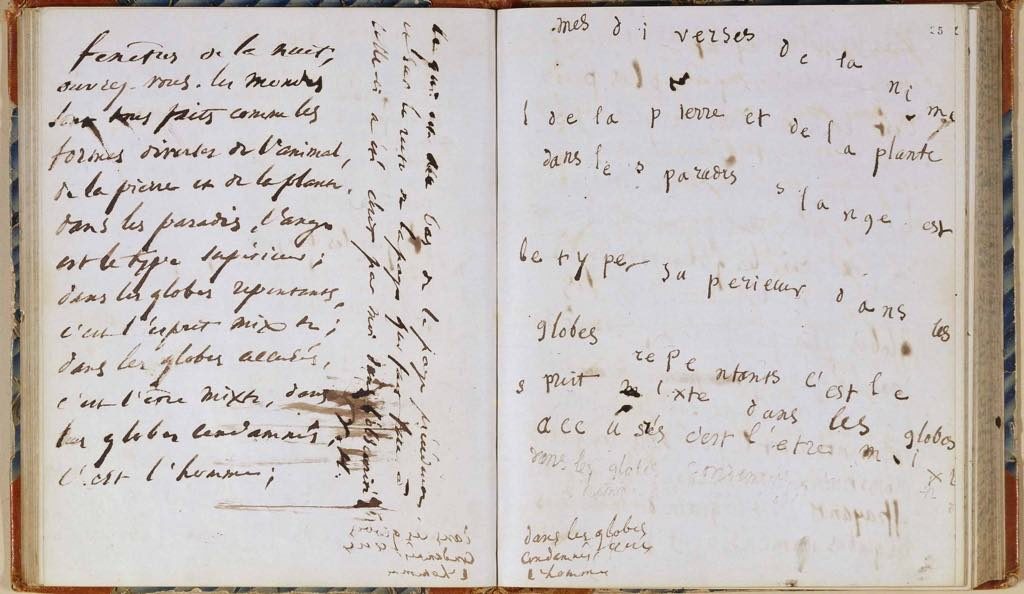

Victor Hugo’s notebooks on spiritualist sessions held when he lived on the island of Jersey are on show, as are drawings and writings produced by people such as Henri Michaux, Jean Cocteau and Antonin Artaud while under the influence of various drugs. Judging from their sketches, Michaux must have been a terrible bore when high, while Cocteau’s drawings are infinitely more interesting.

Inevitably, perhaps, in an exhibition containing so many wonderful documents, the very brief descriptions accompanying them are sometimes maddeningly unhelpful. And more biographical information about some of the subjects would have been appreciated. If you have time to linger in the rooms, do listen to the various performances of texts made available on headphones, which offer the opportunity to reflect upon the exceptional nature of such “extreme” writing.

Be warned, however: you will be lost if you do not speak or read French, as no translations are available. For those conversant in French, this exhibition is unforgettably urgent and moving.

Favorite