|

|

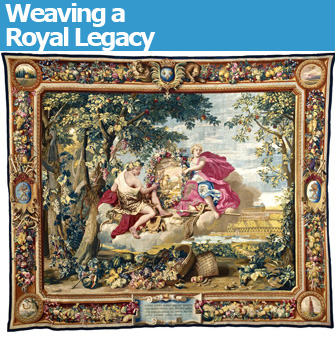

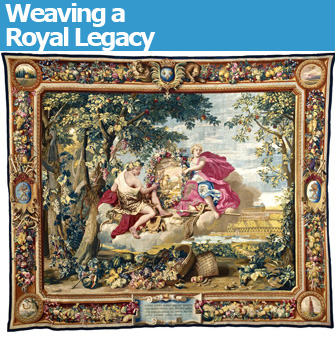

“Automne” (c. 1668), after Charles Le Brun. © Lawrence Perquis, Mobilier National |

The historian Ernest Lavisse, whose manuals on the history of France influenced generations of teachers, dismissed Louis as a philistine with no feeling for the arts, except as instruments …

|

|

“Automne” (c. 1668), after Charles Le Brun. © Lawrence Perquis, Mobilier National |

The historian Ernest Lavisse, whose manuals on the history of France influenced generations of teachers, dismissed Louis XIV as a philistine with no feeling for the arts, except as instruments for his own glorification. An exhibition being held at the Château de Versailles, “Louis XIV: The Man and the King” (through Feb. 7) seeks to redress this too-arbitrary judgment, while another – smaller but no less important – at the Galerie des Gobelins, “Fastes Royaux,” emphasizes Louis’s hitherto-unexplored collection of tapestries.

Part of the reason that this collection has been neglected may be that most of the 2,500 15th-, 16th- and 17th-century tapestries owned by Louis were destroyed by fire in 1797 during the Directory. Louis had inherited an estimated 400 tapestries from his predecessors, including the art-loving François I. Others he seized from Nicolas Fouquet, the ill-fated Superintendant of Finances, who flew too close to the sun when he built a magnificent château at Vaux le Vicomte, rousing the king’s anger, and suffered a fall without parallel in French history.

Another of Fouquet’s attempts to be more royal than the king was creation of the Maincy tapestry studios. Henri IV had already founded the Saint Marcel atelier, the ancestor of the Gobelins tapestry manufacture, at the beginning of the 17th century, but it was Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Fouquet’s replacement as minister of finance, who, in 1662, created Gobelins by regrouping its predecessor, Faubourg Saint-Marcel with the Maincy Studios and various independent Parisian tapestry makers. The painter Charles Le Brun, who had worked for Fouquet, was put in charge of Gobelins as well as of the painting and decoration at Versailles.

Tapestries had been an established art form in favor with royalty, aristocracy and the bourgeoisie since the Middle Ages. During Louis XIV’s reign and under Le Brun’s direction, Paris and the Gobelins replaced Brussels as the centre of tapestry manufacture.

Many of the tapestries included in this small but stimulating exhibition were buried deep in the Gobelins vaults and have only recently been rediscovered. Nor are tapestries the only discoveries on view for the first time. The exhibition’s organizers have also brought out a table that is over 2.65 meters long, with a stone surface and gilded borders and legs, that originally belonged to an ensemble of eight made for the Château of Marly (built for Louis after 1679 by his architect, Jules-Hardouin Mansart). The table is presented beneath a splendid painting representing Louis XIV’s siege of Lille, the work of Adam Frans van der Meulen, originally intended for Marly and now at the Château de Versailles.

The table was actually in the Louvre for a time before being transferred in 1858 to Napoleon III’s Imperial Furniture Depository. It has been restored to something approaching its original state for this exhibition. The painting and the table work particularly well together and will both go to Versailles after the exhibition ends, since Marly was destroyed during the Revolution.

Arnauld Brejon de Lavergnée, the Mobilier National’s director of collections, has organized the tapestries as a stimulating series of confrontations between the various schools and styles of the centuries represented, allowing us to compare a tapestry depicting the history of the Emperor Constantine after a painting by Giulio Romano, for example, with another after Le Brun.

Interesting contrasts occur when looking at tapestries from the stately and highly stylized École de Fontainebleau, such as “The Peasants of Lycie Changed into Frogs” after a design by the short-lived transitional figure, Toussaint Dubreuil, and tapestries after Rubens and the still more dynamic Simon Vouet.

The Rubens is placed over the staircase between the exhibition’s two floors, recalling the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s placement of their own Rubens depictions of the “Life of Constantine.” Still another confrontation occurs near the exhibition’s end with two tapestries, after designs by Le Brun in one case and his rival and eventual successor as director of the Gobelins, Pierre Mignard, in the other. Each portrays Autumn, from sequences on the Four Seasons. Le Brun’s has a much lighter touch and in some ways almost seems to belong to the 18th century, while Mignard’s was inspired by the Carracci paintings for the Palazzo Farnese in Rome. Le Brun’s is elegant and serene, with few figures, while Mignard’s is a crowded, energetic bacchanalia.

The predominant Italian influence, notably by way of Raphael and Giulio Romano, during the two centuries in question is amply attested by tapestries from England’s celebrated Mortlake Factory, depicting various scenes from the acts of the Apostles after Raphael’s originals. Charles I of England bought Raphael’s original cartoons and then asked Mortlake to make tapestries from them. After Charles’s beheading, his considerable collection went on the market, which is how “The Remise of the Keys to Saint Peter” (c. 1630) and “The Miraculous Draught of Fishes” (c. 1630) entered first the collection of Cardinal Mazarin and then that of Louis XIV.

Mortlake tapestries were admired throughout Europe, and several others are on display here. Giulio Romano, though less famous, was possibly even more important in the history of tapestry than his master Raphael. Notable here is an enormous design by him, “Fructus Belli” (The Fruits of War), copied at Fouquet’s Maincy Manufacture from an original commissioned by Ferrante Gonzaga of Mantua and intended to illustrate the horrors of war.

Like the protest songs of the 1960s, Romano’s depiction of war’s evils seems to have had little effect. It certainly did nothing to stop its eventual owner, Louis XIV, who eventually ruined France financially with his incessant war-making. It has to be said that its portrayal of a defeated general and his soldiers in chains is somewhat static and stately compared with, say, Poussin’s depiction of Roman soldiers crushing babies beneath their feet and grabbing terrified women while old men kneel before them begging for mercy.

Gobelins is still an active tapestry manufacture, although the demand for tapestries is considerably less nowadays than it was in Louis XIV’s time. Perhaps it might be an idea to try to convince today’s vulgar rich to spend their money on tapestries of mythological scenes rather than on Rolexes, but that is probably putting pearls before swine. At any rate, the Gobelins remains one of Paris’s treasures, and this exhibition allows visitors to enter an enchanted universe for an hour or two.

Galerie des Gobelins: 42, avenue des Gobelins, 75013 Paris. Métro: Gobelins. Tel.: 01 40 13 46 74. Open Tuesday-Sunday, 11 a.m.-6 p.m. Admission: €6. Through February 7. www.mobiliernational.culture.gouv.fr

More reviews of Paris art exhibitions.

Reader Reaction

Click here to respond to this article (your response may be published on this page and is subject to editing).

© 2009 Paris Update

Favorite