|

|

|

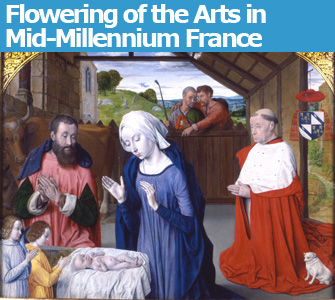

“Nativité au Cardinal Jean Rolin” (c. 1480) by Jean Hey, a Flemish artist working in France. © Ville d’Autun, Musée Rolin

|

The ambitious exhibition “France 1500: Entre Moyen Age et Renaissance,” which opens today at the Grand Palais, offers a nice complement to the show we reviewed last …

|

| “Nativité au Cardinal Jean Rolin” (c. 1480) by Jean Hey, a Flemish artist working in France. © Ville d’Autun, Musée Rolin |

“France 1500” has many other points to make as well, one of them being that the distinction commonly made between the “dark” Middle Ages and the enlightened Renaissance is a fallacy, since the transition from one to the other was a gradual process, during which both Gothic and Antique styles continued to be used.

“France 1500” also sets itself the task of claiming France’s important (and often ignored, according to the curators) place in the flowering of the European arts and humanism during the period. With the end of the Hundred Years’ War in the mid-15th century, France was able to turn its attention to more peaceful pursuits, and new technologies like the printing press were changing the way art was disseminated. While the Italian campaigns of Charles VIII (1483-98) and Louis XII (1498-1515) disrupted the peace, they also had the effect of exposing France to the flourishing Italian arts. At the same time, patrons of the arts like Anne de Bretagne, who was married to both kings, were encouraging innovation in the arts.

As if that were not enough for one exhibition, “France 1500” also provides examples of variations on artistic styles in different areas – Paris, the Loire Valley, Burgundy, Lyon, Champagne, Provence (where the Italian influence was especially strong), etc. – and shows how different art forms influenced each other, placing, for example, painted enamels made with a new technique in Limoges at the end of the 15th century next to paintings that inspired them, or cartoon-like prints made for popular consumption next to the original models to show how the recent invention of printing help spread the arts beyond the reach of the wealthy elite. Medallions, another popular form, imported from Italy, are amply represented. The show even makes a quick foray into architecture and furniture design to give us the full picture of the intertwining of the arts at the time, and provides examples of artworks imported from Italy or made by Italian artists working in France, with one painting by the most famous of them all, Leonardo da Vinci, who was himself imported to France by François I and died there in 1519.

The exceptional works of art illustrating these various themes are far too numerous to mention, beginning with an amazingly sensitive self-portrait by Jean Fouquet in enamel and gold on a medallion. Then one sumptuous

|

|

“Self-Portrait” (c. 1452) by Jean Fouquet. |

illuminated manuscript follows another; don’t miss Jean Bourdichon’s Pietà and depiction of Anne de Bretagne praying in “Grandes Heures d’Anne de Bretagne” and the works by Jean Perréal (note the marvelous portraits in “Louis XII in Prayer” from an illustrated version of Ptolemy’s “Cosmographia”). Of several paintings by Jean Hey, a Flemish painter who worked in France, two are especially remarkable: “Ecce Homo” (1494), in which the deep sadness of Christ’s expression is heartbreaking, and “Saint Soldat (Saint Maurice?) and Donor” (c. 1500-05), with its meticulous depiction of the kneeling donor’s stringy comb over, the soldier’s cottony dark hair and fur cloak, and the reflection of the donor’s image in the soldier’s gleaming armor.

Lovely statues also abound, among them the “Virgin and Child” attributed to Guillaume Regnault (1510-20), with its monumental grace and air of serenity, and the Master de Chaource’s “Pietà” (c. 1500-15) – note the details of the Virgin’s fingers, the suggestion of veins on her hands, her tragic expression and the way one side of her mouth sags as she leans over her dead son.

Upstairs, take the time to study the individualized portraiture, rich garments and wealth of details in the four magnificent panels from a retable painted by the Master of Saint Gilles, two of which now belong to the National Gallery in London and two to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. The retable was probably painted for a church in Paris, and three of these paintings identifiably depict monuments that can still be visited today in or near Paris: Sainte Chapelle and the cathedrals of Notre Dame and Saint Denis.

It is all rather overwhelming, so plan to spend quite a lot of time absorbing the exhibition, or go back for a second visit. The show will be presented at the Art Institute of Chicago from Feb. 26 to May 30, 2011.

Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais: 3, avenue du Général Eisenhower, 75008 Paris. Métro: Champs-Elysées Clemenceau. Tel.: 01 44 13 17 17. Open Wednesday, 10am-10pm; Thursday-Monday, 10am-8pm. Admission: €12. Through January 10, 2010. www.rmn.fr

Order books about France in 1500 from Paris Update’s Amazon store at no extra cost. Click on your preferred Amazon location: U.K., France, U.S.

Support Paris Update by ordering books from Paris Update’s Amazon store at no extra cost. Click on your preferred Amazon location: U.K., France, U.S.

Reader Reaction: Click here to respond to this article (your response may be published on this page and is subject to editing).

More reviews of Paris art shows.

© 2010 Paris Update

Favorite