They are designed by the top experts in the field. After production, they are kept in an undisclosed storage facility, guarded as closely as the national gold reserves. When the big day approaches, they are shipped in double-sealed containers to government-run centers throughout France and placed in safes (all this is true) whose exact locations are known only to a few insiders sworn to secrecy.

No, I’m not talking about the crown jewels. France doesn’t have any crown jewels anyway, because it doesn’t have any crowns. Or, since a while ago, any heads to put them on. But that’s a different story – I’m talking here, of course, about the questions for the bac philo.

As I explain every year in this annual recurring feature (the 2016 article links to 2015, which links to 2014, which… even if you flunked sixth grade, you can do the math), in order to graduate, French secondary school seniors have to take a standardized test called the baccalauréat, a.k.a. the “bac.”

It’s a multi-day, comprehensive, staggeringly difficult exam. How difficult? Here’s a hint: students are allowed to use dictionaries – but only for the Greek and Latin segments.

Note to American high school students who happen to be reading this: yes, Greek and Latin. In high school. And that’s not even the hardest part of the test. The hardest part, the mental ordeal that everyone dreads the most, is the philosophy section.

Note to the parents of American high school students who happen to be reading this: if you don’t have smelling salts, try ammonia. When your kids come to, tell them that they’d better start doing more chores around the house or you’re moving to France.

Yes, the French love philosophy. They discuss it in cafés, they read about it in magazines…

they refer to it fondly as “philo” and they teach it to children. Well, teenagers.

In fact, they love it so much that they publish the topics for the bac philo in the newspapers (and Philosophie Magazine) every June.

Which is how I get my hands on them. And then, to set a good example for American 18-year-olds who, as I was at that age, are more preoccupied with sex, music, movies and sex than Rousseau, Foucault, Hobbes and Durkheim (whose works served as the basis for this year’s bac philo), I take the test.

Sort of…

(These are the actual questions from the 2017 bac philo.)

Is everything that I have the right to do fair?

Obviously not. To name just a few examples:

I have the right to talk loudly on my cellphone everywhere all day long, which isn’t fair to the people around me who are trying to work, converse, think, remain sane or refrain from strangling me with my earbud cord.

I have the right to stop bathing, which wouldn’t be fair to the people who have to smell me.

I have the right to borrow money from everyone I know and never pay it back, which wouldn’t be fair to, well, everyone I know.

I have the right to be a thoughtless jerk, like the owner of the massive gas-gulping SUV who took up one and a half spots in a parking lot in Saint Malo two weeks ago, which I had entered because it’s really hard to park in Saint Malo and the sign outside said there was one spot left, and which I ultimately had to leave, costing me three euros, 15 minutes of my life and 30 systolic blood pressure points, which isn’t fair to me.

According to a widely held belief among Parisians that I have heard countless times but doubt is actually true, I have the legal right to throw two parties per year, one on my birthday and one on New Year’s Eve, and play deafeningly loud, mind-numbingly simplistic pop music all night long with supposed immunity from getting a citation for disturbing the peace, which wouldn’t be fair to neighbors trying to sleep. And would be especially unfair to people who live in large buildings and have 364 neighbors, all with birthdays on different days not including December 31st.

And I have the right to combine my answer to this question with my answer to the next one, which isn’t fair to the French students who took the actual bac last week and had to answer both:

Does defending one’s rights always mean defending one’s interests?

No! To take some of the examples just cited, it’s not in my interest to defend my right to stop bathing, paying back loans and observing the basic principles of human decency. Because then no one would come to my birthday party, and I wouldn’t get to defend my right to annoy my neighbors. Which isn’t in my interest either, because then I won’t get invited to their New Year’s parties.

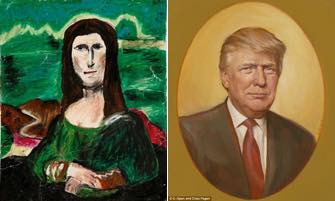

Does a work of art necessarily possess beauty?

Applying the standard picture-to- word conversion rate, I am going to answer this question with a 4,000-word essay:

In conclusion: no, no, no and noooooooooo!

Can knowing result merely from observing?

Hmmm. I’d like to address this answer to the philosophy professor who came up with this question:

ARE YOU OUT OF YOUR NIETZSCHING MIND? You’re asking this of 18-year-old heterosexual boys? Walking hormone factories who spend about 80 percent of their waking hours ogling women they wish they could have sex with? You’re asking them if observing equals knowing?

No, it most definitely does not. Dammit.

To find happiness, must one seek it?

It helps. But it’s not necessary, so no. Even people who base their happiness on the willful accomplishment of preset goals (getting a good job, finding the right spouse, getting off for time served, etc.) can be elated by unexpected discoveries and opportunities: finding money in the street, chancing upon a beautiful sunset, keying an SUV…

Can we free ourselves from our culture?

So far the answers to all the questions have been “no,” so it’s refreshing to have one to which I can, at last, answer “yes.” It is very difficult, but I think that it’s possible for certain people to free themselves from their culture. Like Matt Damon’s character in The Martian, who even gave up Instagramming and Thanksgiving dinner.

On the other hand, it seems to be wholly impossible for our culture to free itself from certain people. We could start with Justin Bieber, Paris Hilton, Mel Gibson and the entire Kardashian family.

Can reason justify everything?

Once again, no. For example, there’s no reasonable reason why Justin Bieber is still in the public eye. Let alone ear.

There’s no justifiable justification for the push bars on this double door on the second floor of a building giving onto a courtyard off Rue de Courcelles:

There’s no rational rationale for this street sign:

And there’s no explicable explanation for why I should have to answer both this question and the next remarkably similar one:

Can reason be misused?

The answer here is an indisputable, resounding yes. And the proof is: I just misused my own capacity for reason by concocting these answers.

The next new C’est Ironique will appear on July 5.

* Photo credits: Sonicdrewdriver: Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0. Japanexperterna, CC BY-SA 3.0. Honza Groh (Own work) [GFDL or CC BY 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

FavoriteAn album of David Jaggard’s comic compositions is now available for streaming on Spotify and Apple Music, for purchase (whole or track by track) on iTunes and Amazon, and on every other music downloading service in the known universe, under the title “Totally Unrelated.”

Note to readers: David Jaggard’s e-book Quorum of One: Satire 1998-2011 is available from Amazon as well as iTunes, iBookstore, Nook, Reader Store, Kobo, Copia and many other distributors.

Very amusing. I believe David has reached a new level of erudition, and should be awarded a Bac Philo with oak leaf cluster. In addition, whomever delivers the sheepskin (are there enough sheep still roaming around in the Tuileries to provide the skins?) should pin a small ribbon on his lapel so he can appear even more important than he already is. A tiny lamb chop might be appropriate.

Ohh, seven subjects at one stroke, that’s quite a feat. To find joy, I had to click on the link to the paper, so in a way, yes, to find happiness one must sometimes seek it. Now, I am awaiting David’s philosophy textbook, especially the chapter on ethics.