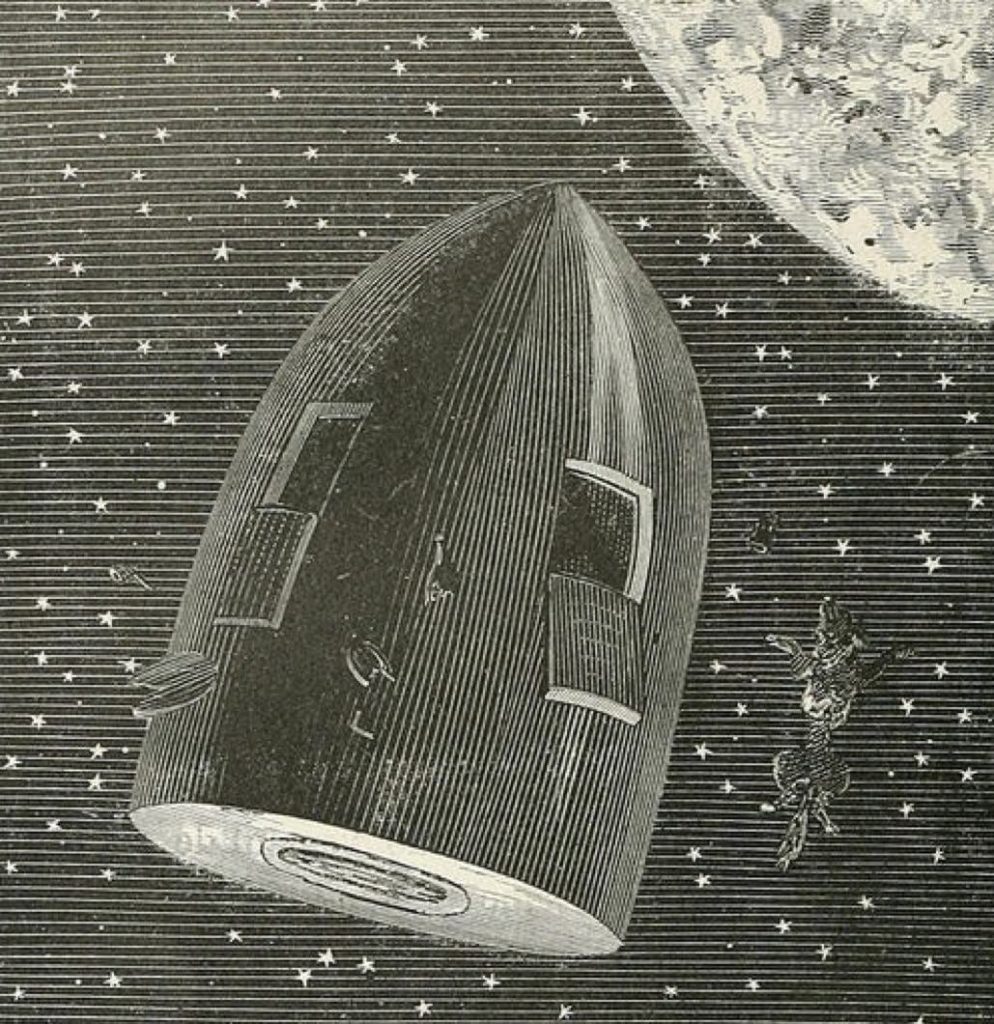

Science fiction has traditionally been dominated by the English-speaking world – think of authors like Ray Bradbury and Ursula Le Guin, and movies like the Star Wars franchise – but France has a surprisingly long pedigree in the field. The first sci-fi text in English, widely considered to be Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, was written in 1818, but as long ago as 1657, the freethinking French writer Cyrano de Bergerac wrote a novel about the narrator’s journey to the Moon and his encounter with an alien civilization there. L’Autre Monde ou les États et Empires de la Lune (Journey to the Moon) also contains the first description of a rocket, which is used by the hero to return to Earth.

In Voltaire’s 18th-century novella Micromégas, a kind of science-fiction version of Candide, a giant extraterrestrial from Sirius finds himself exiled from his home world and ends up on Earth, where he is astonished by the earthlings’ insistence that the cosmos was created for their own benefit. Like Candide’s memorable ending with the admonition that we need to cultivate our own garden, this tale ends in an unforgettable manner: Micromégas promises his hosts on Earth that he will gift them a book explaining the meaning of life when he leaves. He does, and when the volume is opened, it is entirely blank.

I would like to suggest two very readable classics of French science fiction, both of which have accomplished English translations. Jules Verne is the father of modern sci-fi, but an early work, Paris au XXe Siècle (Paris in the Twentieth Century), was not published until 1994, even though it was completed in 1863. Verne’s publisher thought it too pessimistic for readers, and the manuscript was presumed to have been destroyed. In 1989, in a development straight out of a sci-fi adventure, Verne’s great-grandson had a locksmith open a hefty bronze safe that had passed down unopened in the family. Inside was the manuscript.

The protagonist of Verne’s novel, which is set in 1960, is 16-year-old Michel Dufrénoy, who feels alienated in a dystopian society that prizes industry and technology over literature and the arts. He finds redemption in love with a similar rare soul.

The rediscovery of the novel changed the standard perception of Verne as a writer who had become progressively more cynical as he got older. His misgivings about the future were partly related to the fact that, while he was composing the story, Paris was essentially one large construction site for Baron Haussmann’s urban-planning project. Like many of his contemporaries, the author felt that the capital was being destroyed in the name of progress. Paradoxically, today we view this remodeling as a beneficial and integral part of the city’s charm.

The greatest 20h-century sci-fi writer in French is undoubtedly J.-H. Rosny aîné, the pen name of Joseph Henri Honoré Boex (1856-1940). Rosny was originally from Belgium and spent several years in England before settling in Paris for the rest of his life. He was a prolific correspondent and well-connected in the literary world through his oversight of the prestigious Académie Goncourt.

Rosny’s work is now beginning to be rediscovered; it is a mystery why it was so long overlooked (though not by sci-fi writers: the French equivalent of the Hugo/Nebula award bears his name), and he was even considered for the Nobel Prize in Literature in the 1930s. His masterpiece is Les Navigateurs de l’Infini (The Navigators of Space, 1926), which dramatizes the voyage of three astronauts (the word was coined by Rosny) to Mars, where they encounter a series of lifeforms. The dominant species is a three-legged, six-eyed race that they christen Tripeds.

One of the travelers, Jacques, falls in love with a female Triped, whom he calls Grace (the Tripeds do not have mouths but communicate via sign language). The narrative then shifts to focus on their unlikely relationship. With its stress on love and cooperation bridging differences, the story is a veiled critique of colonialism.

Rosny wrote a sequel, The Astronauts, depicting a return trip to Mars and the visit of some Tripeds to Earth. As in the case of Verne’s lost novel, it is a mystery why the second part was never published until 1960, long after Rosny’s death.

In recent years, there has been renewed interest in French sci-fi, with the publication of critical studies by such writers as Sorbonne professor Simon Bréan and the production of the well-received French TV series Osmosis and Ad Vitam.

Another sign of this renaissance is the launch of a science-fiction series in 2019 by major Paris book publisher L’Harmattan, beginning with Rosny’s The Navigators of Space.

With the fields of science, technology, engineering and mathematics still dominated by the English language, it is cause for celebration that French science fiction, the genre that considers the long-term implications of technological advances, is finally getting its due.