There are many affinities between science fiction and detective mysteries/crime drama. When faced with an unknown planet, future or world, or with beings very different from what we have known, we are forced to work out the lay of this unfamiliar land, and it can take a while to understand what is going on. We had to wait until the end of Season 1 of Westworld (HBO, 2016-), for example, to discover that there were two different narrative strands involving the same character and occurring many years apart.

We also seek someone like ourselves to latch onto as a guide and doorkeeper, often viewing events through the singular perspective of their eyes. This character is usually the narrator or protagonist, and while we might empathize with them, sometimes it is an unlikeable or even reprehensible figure, well-known examples being the narcissistic predator and hebephiliac Humbert Humbert in Vladimir Nabokov’s brilliant novel Lolita (1955) and Dexter Morgan, the affable serial killer in Dexter (Showtime, 2006-13).

Arzach, a series of short graphic stories from the 1970s, requires sharp deductive abilities on the part of the reader since the stories are – with the exception of a couple of panels – entirely wordless. They depict a strange world seen through the perspective of the title character, a brooding man who might not even be human. As if to reflect multiple possible meanings, his name is written differently in each story, with variants including Arkak and Harzakc, though Arzach is generally preferred, given that it’s the title of the first story.

These adventures were the brainchild of Mœbius, a pen name used by artist Jean Giraud (1938-2012) for his science-fiction work – he saved his real identity for the rest of his output, including the epic Western series Blueberry, which features the ambivalent cowboy protagonist Mike Blueberry. When Giraud died, former French Culture Minister Jack Lang remarked that France had lost two great artists – Mœbius and Jean Giraud – with the death of one man.

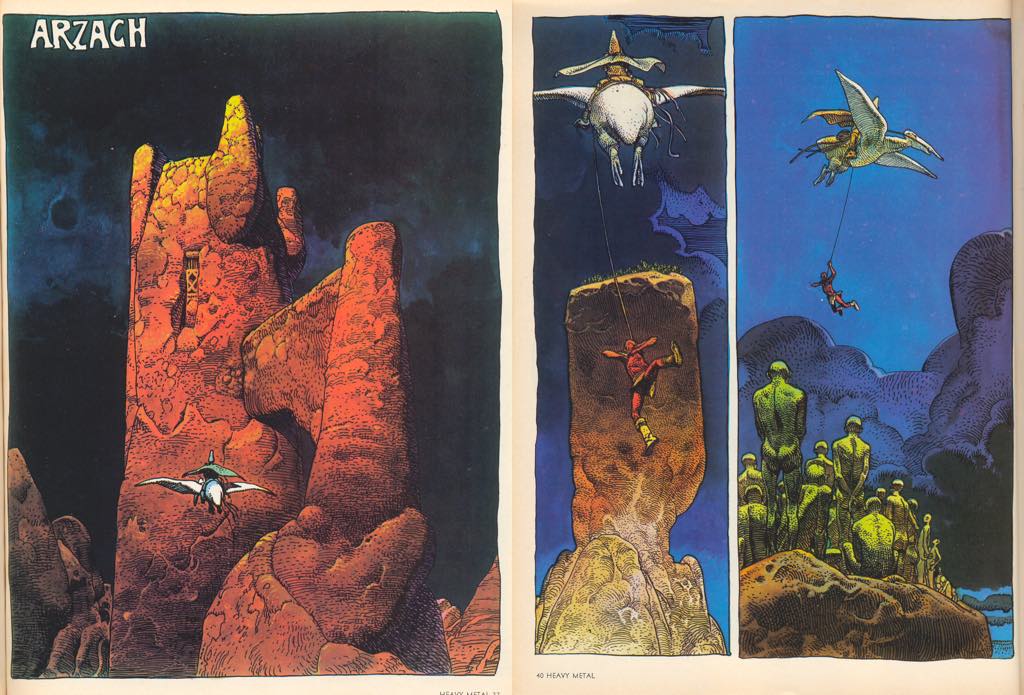

Sci-fi and fantasy are sometimes called “littérature de l’imaginaire” in French, and imagination is a prerequisite for tackling – and enjoying – this mysterious and creative world. In the first panel of the first story, Arzach, a splash covering the entire page introduces us to the enigmatic figure. We see him from behind, riding a pterodactyl-like winged creature. This view, with none of his features visible, hints from the very start that much is concealed about this man. He is riding toward a sand-colored castle-like structure that looks organic.

It is clear that this is an alien world. The colors are subdued yet striking, with many different hues in the dark sky and sandy rocks. Arzach – we know this must be him as the name breaks the fourth wall toward the top of the page – is seen off-center in the image, resisting any neat symmetry. It is as if Mœbius is signaling to us that there will be no pleasing explanations or gift-wrapped narrative here. Arzach is dressed in clothes and a peaked hat that suggest a soldier. The first panel hints at an itinerant knight or perhaps a wandering cowboy.

The strange story continues with Arzach spying a woman undressing through an open window. He pauses to watch her – our first indication that he does not follow any code of nobility – and is then disturbed by an aggressive male standing at the top of the edifice, who seems to threaten him. Arzach deftly lassos him and lifts him off the rocky summit then flies on with the man hanging from his steed. He finally deposits the man in the ribcage of some gargantuan animal’s skeleton, where he is left dangling, possibly to be asphyxiated. Arzach returns to the beautiful woman, who had been seen only from behind. When he steps inside her quarters, she turns around to reveal a grotesque canine-shaped face with yellow eyes and a long blue tongue. He promptly leaves.

This first story sets the scene for the rest and leaves many unanswered questions. Who is Arzach? What is the woman’s species? Had he gone there with a purpose? Was the belligerent man menacing the woman? What kind of creature has such a skeleton? This incredibly rich eight-page story devoid of dialogue or explanations gives our minds a kind of workout as we try to piece together the scant clues scattered throughout the beautiful panels.

Rather than frustrating the reader, this quest for meaning is alluring, perhaps because life often challenges us in the same way, with situations and people sometimes defying ready explanations or definitions. This intriguing quality of Mœbius’s work is especially interesting in light of the French word for plot: intrigue.

Along with the singular delights of the plots and the ravishing artistry, another reason for reading Arzach lies in the fact that we are already somewhat familiar with this world. One of Mœbius’s most devoted fans is George Lucas, who contributed a preface to Byron Preiss’s The Art of Mœbius (1989). The desert landscapes of Arzach’s planet have affinities with many settings in Star Wars. On his blog Kitbashed, Michael Heilemann discusses this influence and notes how a probe in the movie franchise was likely copied from a background image in Arzach. Other fans include Ridley Scott and Steven Spielberg.

As I’ve emphasized throughout this series, French sci-fi not only deserves to be better known but also has impacted English-language popular culture much more directly than we might have ever imagined.

All of the Arzach stories are readily available online (here, for example) and compiled as videos on YouTube.

This article is part of a series of essays on French science fiction by Prof. Paul Scott. The others can be read here, here, here, here, here, here and here.

Favorite