Valérian and Laureline are the eponymous heroes of a sci-fi graphic series like no other. For one thing, the 24 tales, which appeared over a span of over four decades, between 1967 and 2010, echoed societal changes during a period encompassing everything from the turbulent end of the 1960s and the Moon landing to the end of the Cold War and the rise and fall of Thatcherism and Reaganomics.

They also reflect the evolving perspectives of their creators over most of their adult lives. Pierre Christin (b. 1938), who created the series, was a professor of French literature at the University of Utah then at Bordeaux University. Jean-Claude Mézières (also b. 1938), the illustrator, later taught university classes on comic art at the Université Paris VIII-Vincennes-Saint-Denis.

This scholarly pair were childhood friends who reconnected in the United States when Christin was teaching there and Mézières arrived in 1965 on a quest to learn more about the myth of the cowboy. They shared a dislike for the authoritarian government of Charles de Gaulle, and the United States seemed to be a nation on the brink of major social change, with the youthful leadership of JFK ushering in the decade and desegregation finally putting an end to unjust racial laws.

Their unlikely reunion led to a creative partnership, and they submitted “Bad Dreams” (“Les Mauvais Rêves”), the first Valérian and Laureline story, to René Goscinny, author of the Asterix series and editor-in-chief of Pilote, a magazine that served as a launchpad for many of the best graphic novelists of that generation.

That first story – a little shorter, with less-refined artwork than those that followed – introduced the premises of the plot. The setting is the 28th century, exactly seven centuries from today, in 2720. Galaxity is the capital of Earth and the headquarters of the Terran Galactic Empire. Since the discovery of teleportation through time and space in the 24th century, the planet’s population has become indolent, and work has all but disappeared. A hierarchy of a few hundred technocrats and a kind of police service of spatio-temporal agents govern this vast empire. People’s dreams are manipulated to keep them happy, our first clue that all is not well in this apparent utopia.

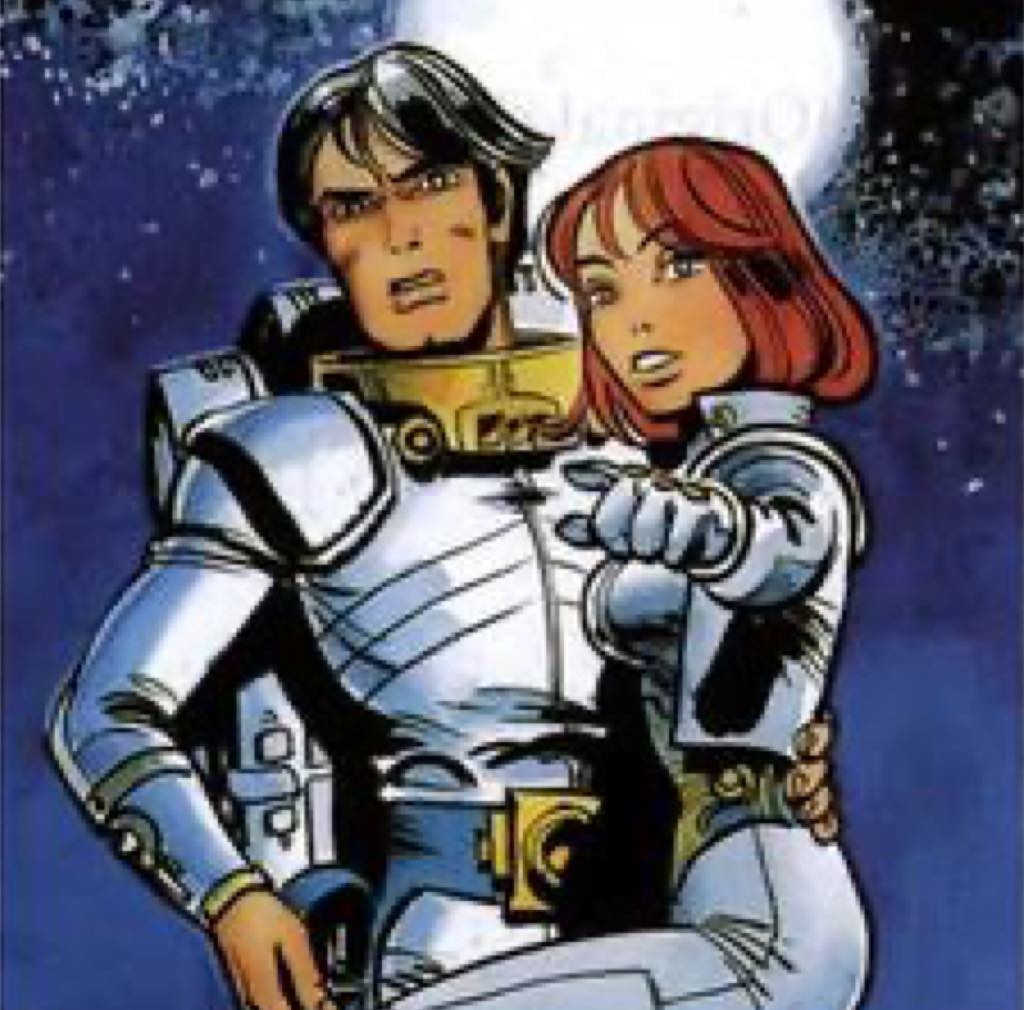

When we first meet Valérian, a spatio-temporal agent with handsome, chiseled features, he is alone and constructing a mathematical sculpture, an indication that he is a solitary artistic type. His leisure time on a planet in the Arcturus system is disturbed when he is summoned back to Earth for a mission.

He is told that people are distraught because they are having bad dreams and that “all Terrans do nowadays is dream.” The culprit is Xombul, the empire’s dream superintendent, who has disappeared but is traced to 11th-century France, where he has traveled to tap the powers of a sorcerer called Albéric. Xombul, a recurring figure in the stories, is a megalomaniac bent on domination (he crowns himself the first emperor of Galaxity).

We meet Laureline, a young peasant, when she saves Valérian from entangled foliage after his first night in medieval France. Later, she is hooked up to a mnemonic machine, a super-education device, eliminating the technological power differential between them. When she works out that he is from the future, she insists that he must take her with him since strict protocols regulate time travel (agents can only use tools from the period in which they venture, for example).

There are evident nods to James Bond in the series, particularly in the camp villainy of Xombul, and to Doctor Who, but these similarities are slight, and the series is original in many ways. Laureline, for example, is an enterprising woman who is not relegated to sidekick status. Far from being a sexualized damsel in distress, she often rescues Valérian from harm’s way. She is also his intellectual superior, running rings around him as of the first story. This is a far cry from standard espionage fare like James Bond, in which the role of women is to beguile or seduce. Following the dynamic between the central pair is one of the pleasures of reading the adventures in sequence.

The plots also depict people of color as important characters at a time when they would have only appeared as security guards or store assistants in comics from mainstream publishers like Marvel and DC.

Valérian and Laureline was recently published in seven albums to coincide with the release of Luc Besson’s film Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets (2017), though the impact of the stories is best seen in the director’s earlier masterpiece, The Fifth Element (1997) – unsurprisingly, since Mézières was on the production team.

These adult-oriented stories have been widely influential, notably on Star Wars. When Mézières saw the French premiere of the first film in 1977, he thought that “it looked like an adaptation of Valérian for the big screen.”

Valérian and Laureline became more political over the decades, with pointed commentary on environmentalism and extremism, but its real strength lies in Laureline, an empowered figure in the often misogynist category of “supporting actress,” particularly in the male-centric world of sci-fi and graphic novels. Her name has become a popular one in France, which makes it all the more surprising that Besson chose to drop it from the first cinematic adaptation.

The Valérian and Laureline albums are available on booksellers’ sites and can be read in full here.

This article is part of a series of essays on French science fiction by Prof. Paul Scott. The others can be read here, here, here, here, here, here, here and here.

Favorite