Just when you think you know everything there is to know about Frida Kahlo (1907–54), an artist whose life and work have deeply fascinated the public in recent decades, along comes this captivating exhibition at Paris’s Palais Galliera, “Frida Kahlo: Au-delà des Apparences,” to fill in any gaps in your knowledge.

Kahlo is one of those women artists whose biography attracts as much attention as her art, but unlike Louise Bourgeois, for example, she not only expressed herself in her work but also turned her life into a work of art even as she dealt with the extreme pain and disability caused by a devastating bus accident when she was 18 and the emotional turmoil caused by her on-again, off-again relationship with her husband, the then hugely famous Mexican mural painter Diego Rivera, who is now perhaps better known as Kahlo’s consort.

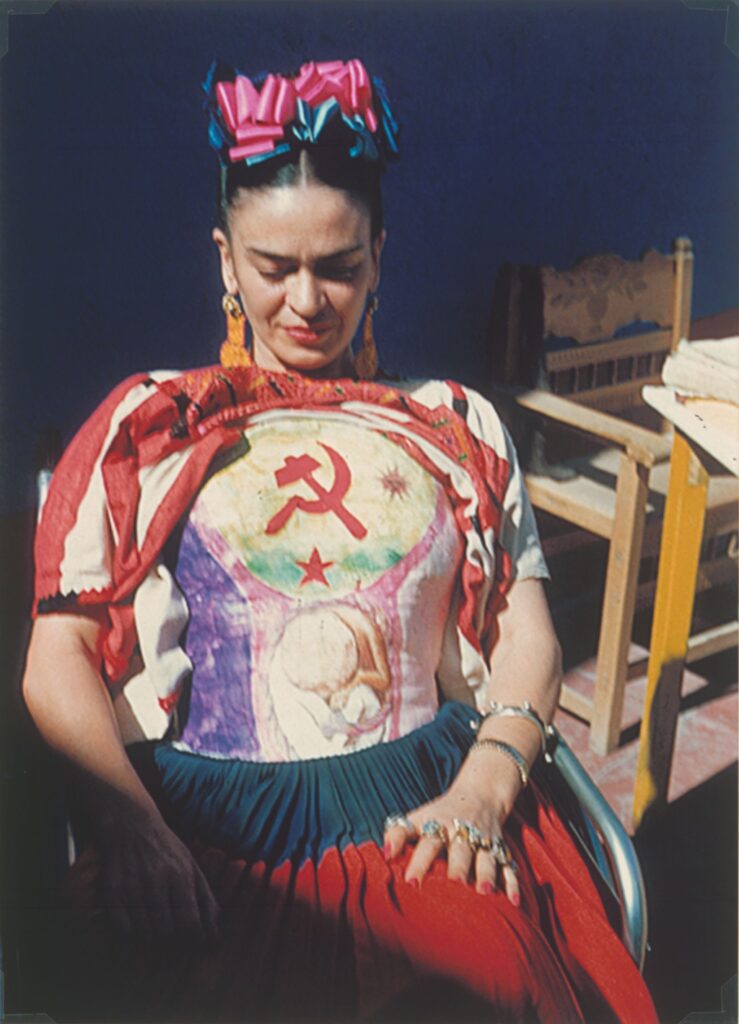

Unlike the exhibition “Frida Kahlo/Diego Rivera: L’Art en Fusion,” at the Musée de l’Orangerie in 2013, which presented the work of the two artists side by side, this show concentrates on Kahlo’s life, not her art, and – since the Palais Galliera is a fashion museum – her clothing. The goal is to “explore the private side of the artist’s life and to understand how she constructed her identity through the way she presented and represented herself.”

The show is rich in photos, documents and artifacts, two hundred of them lent by the Casa Azul (Blue House) in Coyoacán, a suburb of Mexico City, in which Kahlo grew up and lived out her life with Rivera. It, too, was transformed into a work of art and is now the home of the Museo Frida Kahlo.

Kahlo fans already know about the polio she suffered as a child, which permanently damaged her right leg, and the bus accident, during which her body was pierced by an iron rail and her spinal column and most of her bones were broken, but who knew that during the crash her body was sprinkled with flecks of gold leaf from a burst package carried by another passenger, a fitting symbol of the way she turned her disabilities into artistic wealth – she actually started painting while recovering from the accident.

In family photos, we see how the smile on the face of the little girl in images taken by her photographer father, Guillermo, disappears after she contracts polio and becomes introverted and withdrawn in reaction to the bullying she suffered because of her illness. The polio also influenced the way she dressed even as a child, as she attempted to conceal her leg with clothing. Later, the traditional Mexican dresses she adopted, a number of which are on display in the show, also helped to disguise her disabilities.

Kahlo may have been physically bent by these terrible misfortunes, but she certainly wasn’t broken by them. Even the rigid medical corsets she had to wear for long periods became part of her persona and would be painted and shown to the world through photographs.

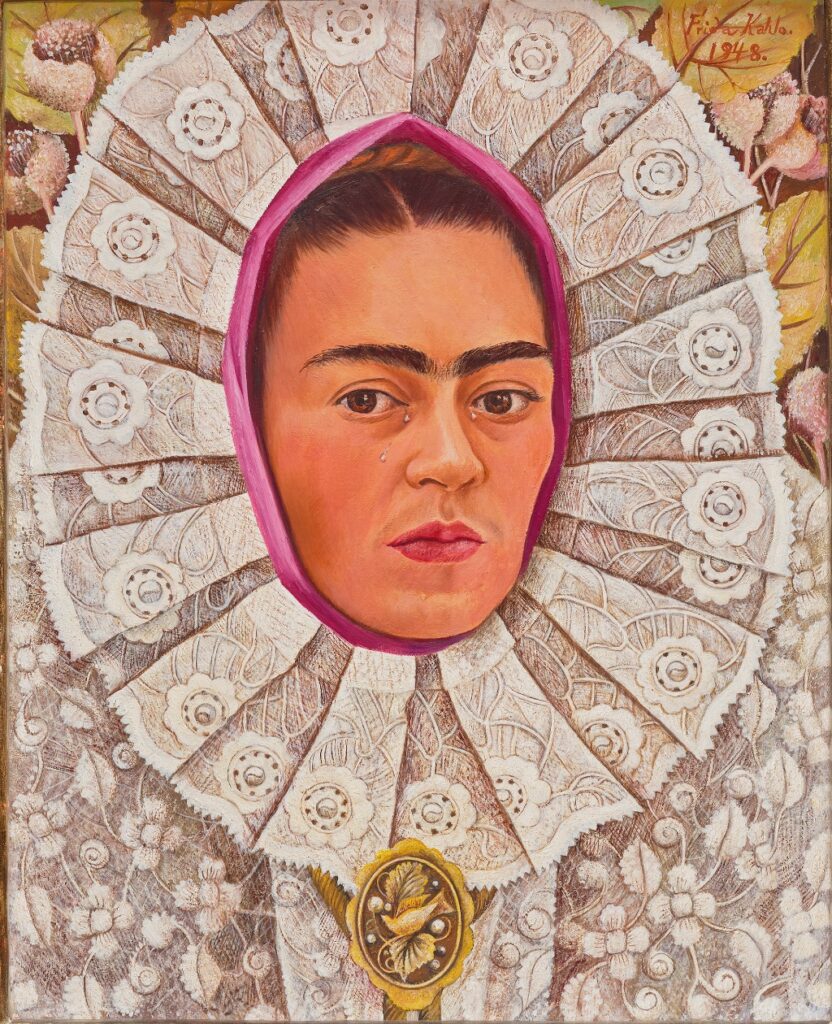

The artworks in the show are mainly reproductions used to illustrate the development of her painting as it related to her life, while a series of votive paintings she collected illustrates the influence of Catholicism and Mexican tradition on her in spite of the fact that she was an atheist and a communist.

I especially enjoyed learning more about Kahlo’s defiant and iconoclastic spirit through some of her letters. After being invited by André Breton to exhibit her work in Paris, for example, she was disappointed to find herself more or less ignored by him there and to learn that the solo show she expected turned out to be a group exhibition. Though she was congratulated for her work by the “heavyweight” artists of the day, including Kandinsky and Picasso, she lost interest in the Surrealists, whom she termed “a bunch of lunatic sons of bitches.” While in Paris, the irrepressible Kahlo also managed to have several love affairs, including one with Breton’s wife, Jacqueline Lamda.

There is much more to learn about this endlessly fascinating woman from this exhibition. Do go – and expect big crowds.

Favorite