After seeing “From Zurbarán to Rothko: The Alicia Koplowitz Collection” at the Musée Jacquemart-André, I sat down to read about the collection of Spanish billionairess Alicia Koplowitz and quickly became fascinated with her life, fittingly described by a French magazine as worthy of a Brazilian soap opera with its tales of money, love, sex and betrayal. Throw in some royal titles won and lost (she is described by Wikipedia as a “former noblewoman”) and you’ve got it all.

But we are here to talk about art, so let’s move on to the exhibition, based on the collection built singlehandedly by this beautiful heiress, always referred to in the press as “discreet,” founder of the venture-capital firm Grupo Omega Capital, whose name is attached to the collection along with her own. This is the first time a large part of it has been shown to the public, offering a rare chance to see these works.

Rather than focus on a single period as many collectors do, Koplowitz’s collection spans the ages, jumping from Greek and Roman antiquity to the 16th century and then continuing erratically up to the present.

In this show, the story begins with a room full of Spanish paintings dating from the 16th to 18th century, including a lovely late work by Francisco de Zurbarán, “The Virgin and Child with the Infant St. John the Baptist” (c. 1659-61), in which the Virgin watches with tenderness and sorrow as the baby Jesus, while casting a knowing glance at the viewer, playfully reaches for an apple being handed to him by John.

This is one of two masterpieces shown in the first room, the other being a portrait of Doña Ana de Velasco y Girón, Duchess of Braganza (1603), by Juan Pantoja de la Cruz (pictured at the top of this page), wonderful for the way the realistically painted face of the beautiful duchess contrasts with the rigid splendor of the gorgeously painted court dress she wears.

This same room also contains two paintings by Goya, one depicting a bloody stagecoach holdup in the forest, with the greenery of nature taking up far more of the picture than the unsettling human drama.

The second room features the work of Italian painters who worked in Spain. I was particularly struck by two accomplished pastels by Lorenzo Tiepolo, each one depicting in closeup the sensual flirtation between a couple while a third person looks on. I also enjoyed the character studies of three young girls and one boy by Pietro Antonio Rotari (1707-62) and a couple of paintings by Francesco Guardi of intimate scenes under the arcades in Venice.

Moving into the late-19th and 20th century, we come across a number of notable paintings. Hanging near a modest still life by Van Gogh, for example, is a handsome and colorful small landscape by Paul Gauguin.

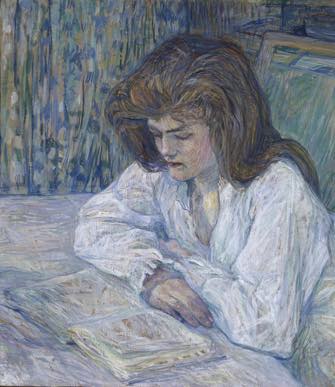

Koplowitz seems to often choose works that are not especially typical of the artist. Picasso’s “Semi-nude with Jug” (1906) is an unusually tender painting of a young girl looking away from the viewer, all in shades of ochre. Toulouse-Lautrec is represented by a portrait of a woman reading quietly rather than one of his wild dancing girls. A lovely Modigliani portrait of a red-haired woman, “Red-headed Woman Wearing a Pendant” (1918), however, is immediately recognizable as the Italian artist’s work.

The next room offers an explosion of colors, with a large-scale abstract painting by Willem de Kooning and a cheery blue and yellow Mark Rothko painting, a far cry from the dark canvases of the artist’s final days.

The last room contains some amazing works, notably a willowy statue of a woman by Germaine Richier, “Leaf” (1948), which reverberates nicely with the rigidly straight Giacometti statue of a large-breasted woman on the opposite side of the room. There are also two of the best paintings I have ever seen by Mi1uel Barceló, both set in Africa, one showing people standing around a lake in the desert and the other people in a boat on the sea. Both brilliantly express the power and harshness of nature while conveying the immensity of big spaces.

Koplowitz writes in the catalogue that her collection has been “a shield that has protected me from some of life’s more difficult moments.” After reading her biography, it seems obvious that she has had many such moments, and it is easy to see how many of these works could offer consolation. I’m glad that she has decided to finally share them and wish she would do the same with her sculpture park, shown in a film at the end of the exhibition, full of wonderful works by the likes of Alexander Calder, Naum Gabo, Anish Kapoor, Richard Serra, Antony Gormley and others.

Favorite