|

|

|

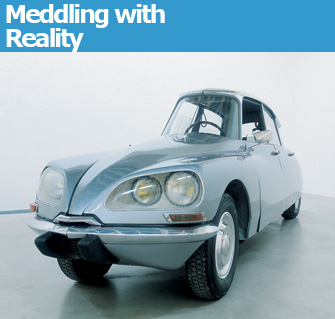

Gabriel Orozco’s “DS” (1993). © Centre National des Arts Plastiques, Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication, Paris

|

You will be forgiven for feeling nonplussed when you walk into the Gabriel Orozco show at the Centre Pompidou. The large square room with ceiling-high glass …

|

| Gabriel Orozco’s “DS” (1993). © Centre National des Arts Plastiques, Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication, Paris |

You will be forgiven for feeling nonplussed when you walk into the Gabriel Orozco show at the Centre Pompidou. The large square room with ceiling-high glass walls opening up to the outside world is strangely empty, aside from a line of small framed works hanging on two walls, a row of miscellaneous objects on the floor and a few simple tables covered with more seemingly unrelated objects.

Orozco also likes to mess with our perception of reality in such pieces as his famous “DS,” a real Citroën DS that has been sliced down the middle lengthwise and seamlessly put back together in a skinny version with one seat in the front and one in the back. More subtly disturbing is a pair of men’s black shoes set side by side, but the wrong way around, with the toes turning outward.

The show seems designed to make visitors uncomfortable. Not only are the titles inaccessible, but unless you have 20/20 vision, you will have a hard time examining some of the smaller items on the tables, since you have to stay outside the black lines taped to the floor about a foot away. If you trespass, you’ll hear a loud automated whistle, which you might think is coming from one of the two Mexican cops roaming around the room. I suspected that Orozco had intentionally created a zone of discomfort for visitors, but it turns out that the museum insisted on the black lines for security reasons, and that Orozco gave in grudgingly and demanded the fake Mexican cops in return to “take care” of the works. He also asked that the room’s windows be left uncovered so that there would be fewer barriers between the “real world” outside and the exhibition inside.

There’s something indescribably intriguing about the work of Orozco, who resists all labels and won’t settle on one medium like a well-behaved artist. After looking at it for a while, you start to get the feeling that something is coming together, moving toward the plus side.

Centre Pompidou: 19, rue Beaubourg, 75004 Paris. Tel.: 01 44 78 12 33. Open 11am-9pm. Closed Tuesday. Métro: Rambuteau. Admission: €10-€12. Through January 3, 2011. www.centrepompidou.fr

Order books on Gabriel Orozco from Paris Update’s Amazon store at no extra cost. Click on your preferred Amazon location: U.K., France, U.S.

Support Paris Update by ordering books from Paris Update’s Amazon store at no extra cost. Click on your preferred Amazon location: U.K., France, U.S.

Reader Reaction: Click here to respond to this article (your response may be published on this page and is subject to editing).

More reviews of Paris art shows.

© 2010 Paris Update

Favorite