The French obsession with singer/songwriter/

chain-smoking drunk/provocateur-par-excellence Serge Gainsbourg is unending nearly 20 years after his death. Now a comic-book artist and screenwriter named Joann Sfar has written and directed Gainsbourg (Vie Héroïque), a love poem to Gainsbourg that manages to avoid hagiography while being mostly entertaining and even innovative in its construction.

Sfar uses an impressionistic style to tell the life story of his hero – and in case there is any doubt that Gainsbourg is just that, a statement at the end of the film quotes Sfar to the effect that he loves Gainsbourg so much that he would rather believe the lies he told than uncover the real story of his life. Sfar has also told the press that the film “is full of lies.”

We will leave it to others to sort out the truth from the lies, but judging from what I learned from the excellent exhibition on Gainsbourg held at the Cité de la Musique in 2008 (for more biographical info on him from that review, click here), there is also quite a lot of truth in the movie.

The first part of the film moves along at a fast clip, telling the story of the cocky little boy who not only sasses Vichy officials when he goes to pick up his family’s yellow stars during the Nazi Occupation of Paris during World War II, but is also able to convince a beautiful art model to disrobe for him so he can sketch her.

We also see the birth of the demons who haunt him: first a grotesque bloated head with a hooked nose he sees on an anti-Semitic poster, which comes to life and becomes his imaginary friend. Later, as a young man, he is accompanied by “Gainsbarre,” an alter ego with long, knife-like fingers and a foot-long beak of a nose who represents his “bad” side.

Sfar amusingly incorporates these phantoms into the film as real characters without being cute about it, and communicates Gainsbourg’s insecurities deftly without hitting us over the head with them. I also appreciated his light touch in letting us know that Gainsbourg has been dumped by Jane Birkin (his live-in lover and mother of his daughter Charlotte, played here by Lucy Gordon with a French accent as atrocious as Birkin’s) not by making us sit through a painful separation scene but by showing him drunk in a nightclub muttering “Jane has left me because I couldn’t stop fucking up.”

While the uninitiated will enjoy the first part of the film, about his childhood and the beginning of his career, only hard-core fans will catch many of the references in the second half. Will non-fans know that Claude Lalanne’s statue L’Homme à Tête de Chou, which Gainsbourg owned, inspired his album of the same name? Or that the black-walled apartment he lives in with Jane Birkin, filled with his strange collections and artworks, is an accurate re-creation of the real thing?

The uninitiated may also be grow increasingly bored as the film goes on: watching the constantly sozzled older Gainsbourg mumbling and slumping is not all that interesting.

Some things remain unexplained – we see that his family survives the war, but we’re not sure how (in fact, they obtained false papers and moved to the city of Limoges). And we never find out what happens to the two sleeping children he abandons when he leaves his second wife.

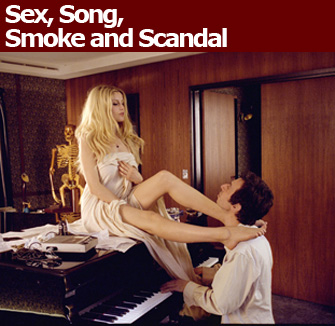

Gainsbourg is played by Eric Elmosnino, who is not only the singer’s double, but is also a fine actor. Kacey Mottet is wonderful as the young Gainsbourg. Model Laetitia Casta makes a fairly convincing Brigitte Bardot, with whom Gainsbourg had a passionate affair, and Yolande Moreau of Séraphine fame has a small part as the drunken chanteuse Fréhel (a role model for Gainsbourg?), once a great star in France, whom the young Gainsbourg meets in a bar.

The parenthetical “Vie Héroïque” in the title at first made me laugh – only a true Gainsbourg could consider the life of this man, as fascinating and creative as he was, to be heroic. But he is incontestably a hero to Sfar and many others in France, who claim to revere him as a poet, although I suspect that it is his provocative, bad-boy side that really appeals to them. (And we mustn’t forget that for many, he was simply a revolting drunk who wasted his talent.)

Gainsbourg changed musical styles and wives

and girlfriends many times, but one thing was a constant in his life: smoke (in the film, we see him as a small child picking up a butt on the beach and smoking it, and he continued to smoke his beloved Gitanes even after having a heart attack). In a telling sign of the times, the smoke disappeared from the film’s handsome poster – which shows a black-and-white profile of Gainsbourg (Elmosnino) with his head tilted back and whorls of smoking drifting sensuously from his mouth – when it was posted in the Métro. Would the always-politically-incorrect Gainsbourg still be a hero today? Maybe we need him back.

Favorite