Like politicians, non-stick frying pans and condoms, I don’t always live up to my promises. Last week, I promised to write this week about my on-the-road lessons in French driving school. But then I realized that there is an aspect of driving in France that deserves to be developed in more depth and detail: the road signs.

Like kissing babies, cooking pancakes and writing humor columns, driving is one of those processes that involve a constant stream of observations, decisions and adjustments that take place on a more or less subconscious level. It requires concentration, but not as much as, say, unwrapping a condom.

That’s why it’s easy to drive while scanning the FM stations, checking the GPS, arguing with your passengers, playing “hot potato” with the cigarette lighter, yelling abuse at other drivers or peeing into a bottle. Or all six at once. Well, maybe not “easy,” but possible. So I’ve heard.

And that’s also why driving in another country can be disorienting. Suddenly, the subconsciously absorbed information has changed: the roads are different, the cars are different, and, most importantly, the bottles you pee in are different. Oh wait — I mean, most importantly, the signs are different.

For Americans, the unfamiliar signs are what make driving in France a disconcerting and at times daunting experience. Well, that and the tailgaters, the speeders, the lane slalomers, the lane creators, the traffic jams, the gas prices, the toll prices, the parking prices, the labyrinthine street layouts, the one-way streets, the two-way but one-lane streets and that filthy wino with no teeth who panhandles by the vending machines at the Shell station on the A6 just north of Lyon. But it’s mainly the signs.

Fortunately, just like toothless winos, many of them look the same as in the States. Stop signs, for example, are exactly alike, and even say “Stop” in English (but with a really strong accent).

Yield signs are similar — they’re still a downward-pointing triangle:

But instead of “Yield” they say “Cédez le Passage.” Note that in French it takes five syllables to say “yield” but only one to say “I love you” (if you elide the initial “e” in j’t’aime). So it pretty much evens out in those situations where you want to say both.

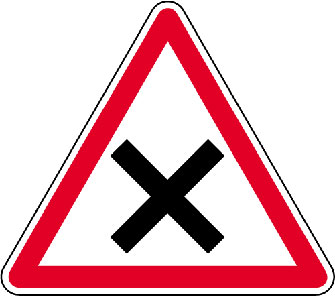

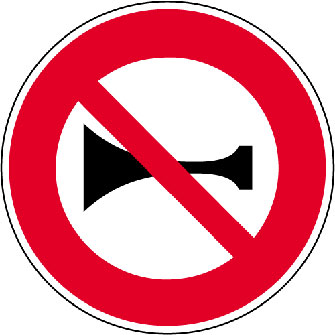

That said, many French road signs are a complete mystery to visiting drivers. Like this one:

It looks like it means “We were going to put something on this sign and then changed our minds,” but actually it’s to indicate an uncontrolled intersection.

Four-way stops do not exist here — where two thoroughfares meet, if neither one is the road less traveled, the French just leave them both bare of signage and rely on the “yield to the right” rule.

The “X” warns you that this is about to happen. In other words, we need a sign to mark the intersections that aren’t marked with any sign. This starts to make sense after you’ve been here for about 10 years.

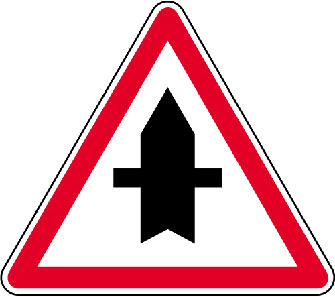

Perhaps even more cryptic is the “Priority Intersection” sign:

Also known as the “Half-In Suppository,” this symbol means that you’re coming to a crossroads and you have the right of way. It’s considered good form not to toss any bottles out of the car while racing through the intersection.

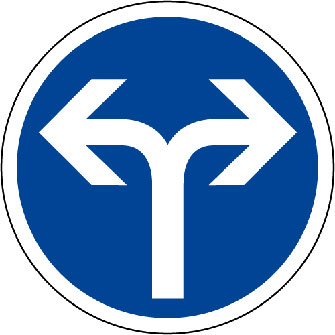

All of this is sufficiently confusing that, as a C’est Ironique Public Service, I have decided to default on my abovementioned promise and devote the rest of this article to explanations of some of the common French road signs. Buckle up:

Next week (I promise!) in “The Long Gear-Grinding Road, Part Two,” I hit the highway with a driving instructor. And then my head explodes. Details on March 27.

© 2013 Paris Update

FavoriteAn album of David Jaggard’s comic compositions is now available for streaming on Spotify and Apple Music, for purchase (whole or track by track) on iTunes and Amazon, and on every other music downloading service in the known universe, under the title “Totally Unrelated.”

Note to readers: David Jaggard’s e-book Quorum of One: Satire 1998-2011 is available from Amazon as well as iTunes, iBookstore, Nook, Reader Store, Kobo, Copia and many other distributors.