It’s May 2018, 50 years after the “events” of May 1968, and commemorative exhibitions are popping up all over Paris. The Hôtel de Ville alone has two exhibitions: outside on the fence is “Quand 68 Prend la Parole,” a show featuring reproductions of the posters produced ad hoc as events developed, and inside is a show of the photos of Gilles Caron, taken on the fly in the hotspots of that action-packed month. It kicked off with the police repressing the student occupation of the Sorbonne, which provoked a mini-war as the students built barricades and tore up the cobblestones of the Latin Quarter’s streets to throw them at charging national police.

Soon after, workers started taking to the streets, too, and a general strike ensued, paralyzing the country. Revolution was in the air. After a while, conservatives, fed up with the chaos, took to the streets themselves to protest and express support for the government, led by the 78-year-old Charles de Gaulle. He did not seem up to dealing with the situation and on May 29 actually disappeared for six hours, raising fears of a revolution. He resurfaced, however, and the next day dissolved the National Assembly and called for new elections. Things calmed down in June, and, in the elections, on June 23 and 30, the right secured a solid majority. The excitement was over. It was time for summer vacation.

The posters, with their strong graphics, brought out the creativity and cleverness of the student and workers’ movements and offered a wide range of messages: “Let’s leave the fear of red to the bulls.” “Yes to the Revolution!” “Beauty is in the street (image of a chic woman throwing a paving stone). “French workers and immigrants united: equal pay for equal work… [repeated in six foreign languages].” “Under 21-year-olds: here is your ballot” (image of a paving stone).”

Inside the Hôtel de Ville, Caron’s photos illustrate “live” the events of those turbulent days. Considered the photographer of May ’68, he covered many major international conflicts – among them the Six Day War, Vietnam, Biafra and the Troubles in Northern Ireland – during his short life; he disappeared in Cambodia in 1970 on a road controlled by the Khmer Rouge when he was only 30 years old.

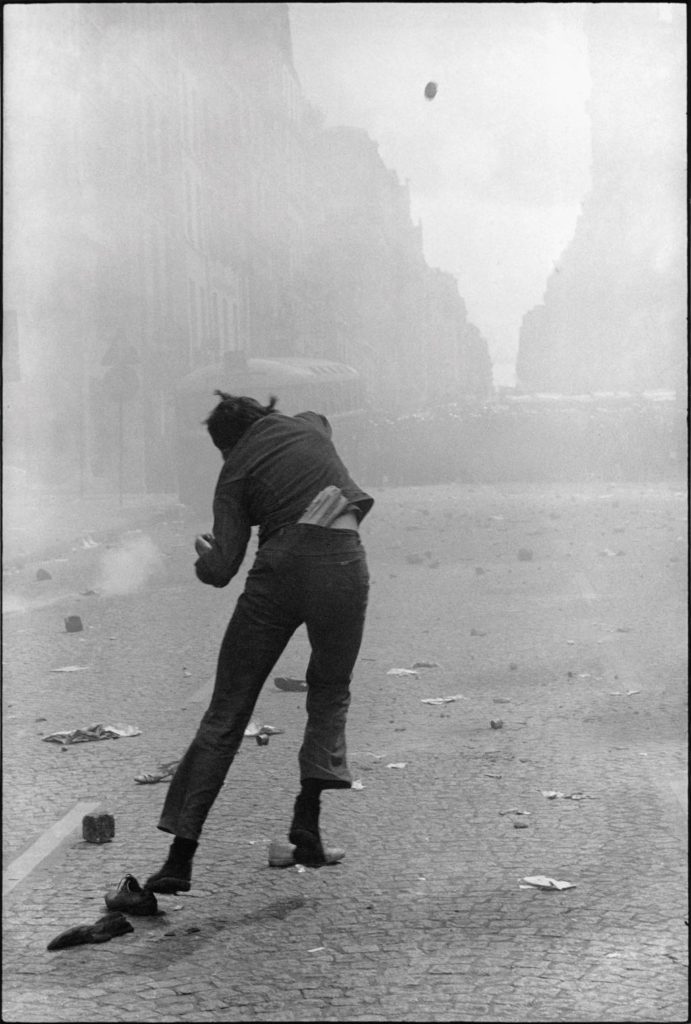

The professionalism of Caron’s May ’68 photos, most of them in black and white, is impressive, especially considering the conditions under which they were taken. They capture the entire series of events: the euphoria of the students as they stretch their new ideological muscles (Daniel Cohn-Bendit mugging at a policeman), the violence in the streets (the high-speed chase of a policemen, baton raised, after a demonstrator, who nearly hits the ground as he runs; the next photo shows the cop striking the fallen demonstrator), the disruption of daily life (people climbing over barricades and upturned cars as they try to go about their business), the backlash of the right (a well-dressed woman and a man in suit and bowler hat marching in a pro-de-Gaulle demonstration on the Champs-Elysées on May 30).

Some of Caron’s most dramatic photos captured demonstrators in the act of launching paving stones.

Another, more peaceful, image of a demonstration organized by the National Union of Students in the Stade Charlety on May 27 takes a long view of the mass of students seated on the ground with a portrait of Mao hovering above their heads. What makes it exceptional is that it manages to be a portrait of an individual as well: a young woman in the foreground who looks directly into the camera.

A garbagemen’s strike in Paris is eloquently depicted by Caron with an image of a sports car nearly buried in vegetable crates with the Eiffel Tower in the background.

The gradual return of “normalcy“ in June is illustrated by Caron‘s photos of masses of near-naked young people – who may have been out on the street throwing paving stones a month before – sunbathing at the Piscine Déligny (a wonderful swimming pool that floated on the Seine until it sank in 1993). On the same day, he took a photo of a bald man in a suit holding a newspaper strolling down the street with his dog and calmly reading the revolutionary posters still plastered on a wall. And another of a man sweeping up the detritus in front of the Sorbonne. The “symbolic revolution,” as Romain Gary called it, was already history.

Favorite

Nice show. I recommend it for readers interested in history of Paris who don’t mind standing in line for hour or so..

On the other hand, do not miss Willy Ronis at the Pavillon Carré Baudouin.