|

|

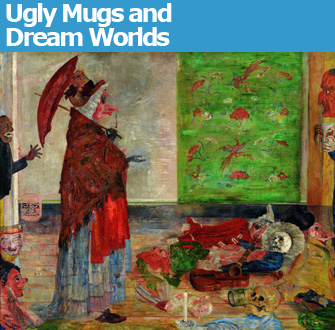

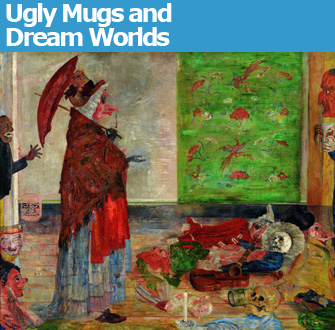

James Ensor’s “Etonnement du Masque Wouse” (1889). © ADAGP, Paris 2009

|

Visiting the James Ensor show at the Musée d’Orsay just after seeing the new exhibition on Fellini across the river at the Jeu de Paume, I couldn’t help noticing certain correspondences, mostly having to do with a shared …

|

|

James Ensor’s “Etonnement du Masque Wouse” (1889). © ADAGP, Paris 2009

|

Visiting the James Ensor show at the Musée d’Orsay just after seeing the new exhibition on Fellini across the river at the Jeu de Paume, I couldn’t help noticing certain correspondences, mostly having to do with a shared taste for grotesqueries and crowd scenes, although Fellini’s approach is far more lighthearted and fun-loving than Ensor’s.

Ensor (1860-1949), who said himself that his work was unclassifiable, is something of an enigma. He was certainly not the first Western artist to compulsively depict the monstrous and misshapen – Bosch and Goya were there long before him – but his preference for this subject matter seems to have grown out of his personal bitterness, if we are to believe the evidence of this exhibition, which starts out with his pleasant but sometimes awkward academy-influenced (he was a dropout of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Brussels) early paintings. Even then, he had a way with light (look at the bottles in “La Mangeuse d’Huîtres”), perhaps because he lived out his long life in an apartment above his family’s seaside souvenir shop (the source of his obsession with seashells, carnival masks and other curios) in Ostend, a town bathed in the light of the North Sea.

The arrogant Ensor, who proclaimed that he had “anticipated all modern movements” and called the Impressionists “outdoor landscape hacks,” soon broke with his early style in favor of a strange, hard-to-read mystical style, which won little favor with the public and the art world. The year 1887 was a turning point for him: Not only did his father and beloved grandmother die, but one of his mystical works was passed over for a prize at the Salon des XX (he was a founder of the artistic movement Les XX, which eventually threw him out) in favor of Seurat’s “A Sunday Afternoon on Grande Jatte Island.” From then on, his grotesque masks and images of death became permanent elements in his work, which also became increasingly satirical and scatological. He wrote that one of the reasons he liked the masks was “because they offended the public, which had received me so badly.”

Paul Haesaerts, author of James Ensor (Abrams, 1959), summed up Ensor well, writing elsewhere that the Belgian painter had “assimilated, destroyed and transformed what was left of Romanticism, realism and even Impressionism… and heralded the brashness and irreverence toward the real that would color the century to come.”

There is certainly much that is repulsive and weird in Ensor’s paintings, but they are also funny, mad, absurd and full of dazzling lighting effects. After a while, they start to grow on you, especially when you get to the last section of the show, which focuses on his self-portraits, in which he depicted himself wearing silly hats adorned with flowers and feathers, as a skeleton, as an insect, as Christ (as both savior and victim of persecution). There is something strangely weird and wonderful about it all.

|

|

Paparazzi (a word derived from a Fellini film) greeting a starlet in “La Dolce Vita |

Weird and wonderful also applies, of course, to Fellini, who once said, “I don’t give a damn about objectivity” and famously peopled his cinematic world with human oddities and outcasts: “exotic men, ugly mugs, naïve and droll girls, funereal women,” etc. (part of a list of types he sought for one of his films).

The very entertaining and well-organized exhibition at the Jeu de Paume, “Fellini: La Grande Parade” (through January 17), immerses visitors in this exuberant director’s world with plenty of film clips, photos, posters, drawings and more. In addition to documenting Fellini’s obsessions – with parades, circuses, whores, bizarre humans, etc. – the show provides lots of interesting tidbits: he didn’t give his actors lines to learn, for example, but just told them what emotion to express and dubbed the dialogue in later (as is common in Italian films), so that they would feel at ease.

We also learn that much of what might seem absurd in his films was really based on reality. The oversized prostitutes were youthful memories, for example, and the flying statue of Christ lashed to a helicopter in La Dolce Vita was based on a newsreel (presented in the exhibition) of a statue of Christ being flown from Milan to the Vatican, watched by crowds of enthralled Italians.

It is also fascinating to see Fellini’s dream book, full of intricate drawings and descriptions of his dreams, many of which later appeared in his films and even in a series of filmed advertisements for the Banca di Roma. A product of his Jungian therapy, this wonderful book is much like Carl Jung’s own dream book, The Red Book, which has just been published for the first time by W.W. Norton.

This exhibition will inevitably inspire visitors to see Fellini’s films again. Luckily, the Cinémathèque Française is presenting a retrospective of his work: “Tutto Fellini” (through December 20).

Musée d’Orsay: 1, rue de la Légion d’Honneur, 75007 Paris. Métro: Solferino. RER: Musée d’Orsay. Tel.: 01 40 49 48 14. Open Tuesday-Sunday, 9:30am-6pm (until 9:45pm on Thursday). Closed Monday. Admission: €9.50. Through February 4. www.musee-orsay.fr

Jeu de Paume: 1 place de la Concorde, 75008 Paris. Métro: Concorde. Tel.: 01 47 03 12 50. Open Tuesday, noon-9pm; Wednesday-Friday, noon-7pm; Saturday-Sunday, 10am-7pm. Closed Monday. Admission: €7. Through January 17. www.jeudepaume.org

Cinémathèque Française: 51, rue de Bercy, 75012 Paris. Métro: Bercy. Tel.: 01 71 19 33 33. Through December 20. www.cinematheque.fr

Buy related books and films from the Paris Update store.

More reviews of Paris art shows.

Reader Reaction

Click here to respond to this article (your response may be published on this page and is subject to editing).

© 2009 Paris Update

Favorite