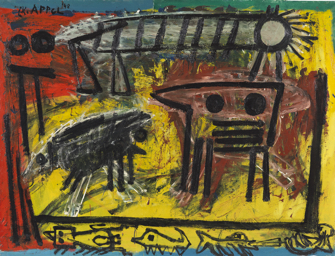

The title of the exhibition “Karel Appel: L’Art Est une Fête!” (“Art as Celebration!”) at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris might lead one to expect a show of art expressing great joy. Far from it. I saw little happiness in Appel’s paintings, many of which have such titles as “Tragic Nude” (1956), “Wounded

Nude” (1959), “Burning Child with Hoop” (1961) or “Tragic Carnival” (1954). Even crustaceans have a tragic outlook in his work – witness the painting “Crying Crab” (1954).

The exceptions are a few cheery, childlike paintings in bright colors at the beginning of the exhibition and many of the sculptures, notably the group called “The Circus” (1978).

Appel (1921-2006), a Dutch artist who lived for a time in Paris and New York, was one of the founders of the short-lived (1948-51) CoBrA movement, which rejected both naturalism and abstraction. As the Museum of Modern Art in New York puts it: “Their working method was based on spontaneity and experiment, and they drew their inspiration in particular from children’s drawings, from primitive art forms and from the work of Paul Klee and Joan

That sums it up nicely, except that I would add that, in Appel’s case anyway, Jean Dubuffet and Willem de Kooning were also strong influences. Like Dubuffet, founder of the Art Brut movement, Apple was fascinated by the art made by patients in mental hospitals.

The importance of Outsider Art to Appel can be measured by his interest in an exhibition of “psychopathological drawings” he saw at Paris’s Hôpital Sainte-Anne in 1950. The exhibition’s brochure described the patient’s pathologies but did not show their works, so Appel created his own and pasted them on the pages. He kept this work, titled “Psychopatho-

logical Notebook” (on show in this exhibition) with him for the rest of his life. He later said: “It was the big exhibition at Sainte-Anne that enabled me to shake off the weight of European classicism.”

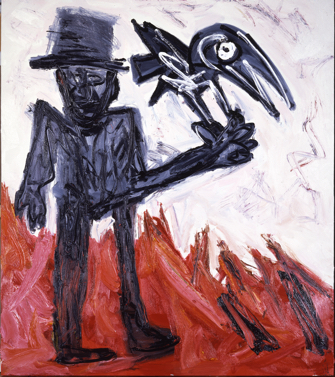

Paris’s Musée d’Art Moderne certainly gets it right when it discusses the “expressive vehemence” of his art. There is almost an aesthetic of ugliness in these aggressively painted canvases, in which the joy inherent in primary colors is tempered by omnipresent black. Some of the paintings are actually frightening, such as the monstrous “Portrait of César” (1956).

Why the dark outlook? Is it related to Appel’s experiences during World War II? The Netherlands was occupied by the Nazis, and as a young man Appel had to go into hiding to escape forced labor. Later, on a train trip

through devastated postwar Germany, he was deeply affected by the sight of children begging for food.

A film presented in the exhibition shows the artist at work, physically attacking the canvas, throwing paint at it and dancing in front of it like a prizefighter facing an opponent. A statement he makes in the film may provide the best clue to the bleakness of much of his work: “I paint like a barbarian in a barbaric era.”

Favorite