Ker-Xavier Roussel (1867-1944) was something of a contrarian. He was classically trained but is best known as a Nabi painter, although he only painted in that style for a time in the 1890s and even then never subscribed to the rules set down by the group, which included his friends Édouard Vuillard and Pierre Bonnard. After that, he went his own way and took up the painting of primarily mythological subjects, ignoring the contemporary world entirely and unconcerned about the risk of appearing retrograde. The Musée des Impressionnismes Giverny is currently holding a rare retrospective of his work, “Ker-Xavier Roussel: Jardin Privé, Jardin Rêvé.”

Roussel was an intellectual and Germanophile who appreciated Nietzsche and wrote poetry. He was known for his black humor and his black moods, which sometimes stopped him from painting and sometimes led him to destroy his works (his friend Vuillard would try to save them, just as he would try to save Roussel’s marriage when the latter cheated on his wife, Vuillard’s own sister). Politically, he was a “utopian anarchist.”

And what of the work of this complicated man? The early paintings have that wavery, ethereal look common to the Nabis, with little modeling, flat planes of color and near-featureless figures.

Two charming paintings here, both titled “The Seasons of Life” (c. 1892) and found in his studio after his death, show his penchant for depicting figures in a landscape. In each one, four women converse, three of them standing and one seated on a rock, against a mountainous backdrop. The seated lady in one of them has white hair, hinting at the meaning of the title.

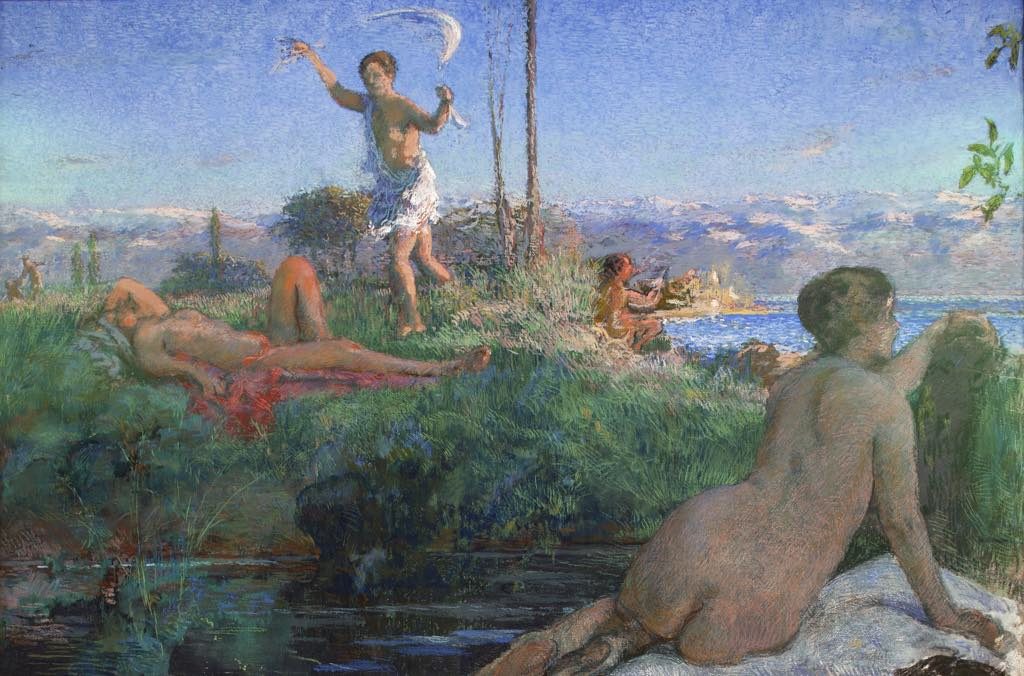

Once he had moved on from his Nabi period into Postimpressionism, toward the end of the 19th century, he left reality behind and painted mostly large-format pastoral scenes filled with nymphs, centaurs and satyrs. While “pastoral” might imply “serene,” however, many of these works were anything but.

A number of violent mythological scenes were depicted in beautiful, bucolic settings, often emphasizing the sexual elements of the story. Figures danced through the paintings as gaily as his contemporary Isadora Duncan, even though the events shown were less than joyous.

In the colorful, light-filled “Eurydice Bitten by a Snake” (c. 1913), for example, we see the nymph Eurydice receiving the fatal bite that will send her to the underworld, from which her husband Orpheus will try to save her, while her fellow nymphs dance gaily nearby.

Many of these works were made with glue paint, which has the effect of brightening the colors but also makes them very fragile. One example is the monumental “Afternoon of a Faun” (c. 1930), with its erotic subject matter: a faun spying on women bathing. One of the women is still in the water, while the other flees through the sunlit rushes, pursued by the voyeur. A pretty scene at first glance, it feels creepily sinister when closely observed.

It was interesting to learn more about Roussel, one of the lesser-known Nabis, who seems to have channeled his demons into his paintings. To get a glimpse of the seemingly happy life he lived, take the time to visit a sweet little exhibition, “Édouard Vuillard et Ker-Xavier Roussel: Portraits de Famille” (through Nov. 3), at the Musée de Vernon in Vernon, the town where visitors to Giverny catch the train to Paris.

This touching show draws the viewer into the homes of the interconnected Vuillard and Roussel families (the two artists became friends in high school and remained close for the rest of their lives) through photos and their paintings of each other and other family members.

Note: The Musée des Impressionismes is seeking funds to buy the painting “La Seine à Vernon” by Pierre Bonnard. Click here if you would like to contribute.

Favorite