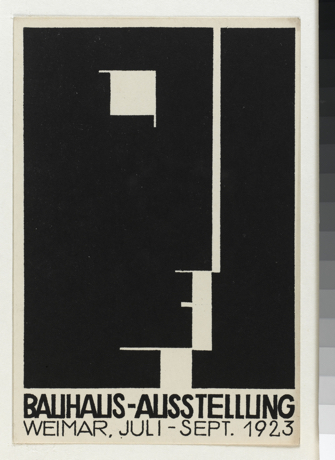

Seeing the exhibition “The Spirit of the Bauhaus” at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs is the next best thing to going to the famous school itself, which would, of course, be impossible, since it was shut down in 1933 after Ludwig Mies van der Rohe refused to submit to Nazi conditions, which included the dismissal of one of its professors, Wassily Kandinsky, considered a “degenerate artist.”

This comprehensive show begins before the beginning, with an overview of the many eras, movements and styles that fed into the creation of the short-lived but so influential Bauhaus school, founded in Weimar, Germany, in 1919, which, according to the curators, “borrowed aesthetic concepts and social ideologies dating from the Middle Ages to the 19th century.”

The school took inspiration not only from medieval guilds – in which artists and artisans with different skills cooperated in the creation of a finished work – but also from the British Arts and Crafts movement, the Austrian Wiener Werkstätte and the Deutscher Werkbund, all of which advocated, like the Bauhaus, the making of total works of art (Gesamtkunstwerks in German) through collaboration between artists and craftspeople working in different disciplines.

The museum draws largely on its own extensive collection to illustrate these predecessors with everything from a 15th-century painted wooden French triptych of the Crucifixion to Edo period (1603-1868) ceramics from Japan (some of them astoundingly minimal and modern-looking) to designs by the amazingly innovative Scotsman Christopher Dresser (1834-1904), who was himself strongly influenced by Japanese arts and crafts and whose work would look avant-garde even today. There are also textiles, furniture and objects from the 19th-century Arts and Crafts Movement.

The show then takes us on a tour of all of the school’s different workshops, accompanied by examples of the work they produced: ceramics; weaving; printing, bookbinding, typography

and advertising; photography; wall-painting; metalworking; stained glass; sculpture; theatre; and architecture.

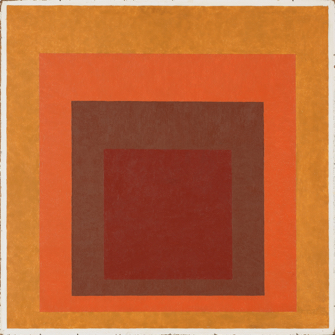

Some of the artists and designers whose work stood out for me in the exhibition include faculty member Josef Albers, who experi-

mented with color in his stained glass and paintings and also designed furniture and objects like the glass bowl with attached holders for salad utensils on display here;

Marianne Brandt, who designed cunning metal objects one would like to have gracing one’s home; and Lyonel Feininger, represented by a number of works, notably a haunting, faintly Cubist painting of a village with a soaring church steeple, “Gelmeroda IX” (1926).

I would have liked to see more on architecture, especially since the Bauhaus was founded by Walter Gropius, who saw the discipline as a focal point for all the others.

Throughout the show, there are photos of and by the school’s students and professors, many of them talented photographers themselves. They were party animals, like most university students, with the difference that their parties were collaborative themed events that made use of their many talents.

The show ends with a selection of 100 contem-

porary objects chosen by designer Mathieu Mercier that supposedly show the influence of the Bauhaus, although I didn’t always see the connection. One piece in particular seemed to embody the school’s philosophy: a simple, practical furniture unit incorporating a desk, chair, lamp and shelves (easy to imagine in a

cramped Paris apartment) by design team Muller Van Severen (Fien Muller and Hannes Van Severen).

A lot of sins have been committed in the name of Modernism, but this look at its origins in the Bauhaus and similar movements shows that later monstrosities were misinterpretations of the ideals of this unusual school that inspired so many followers and continues to be influential today.

Favorite