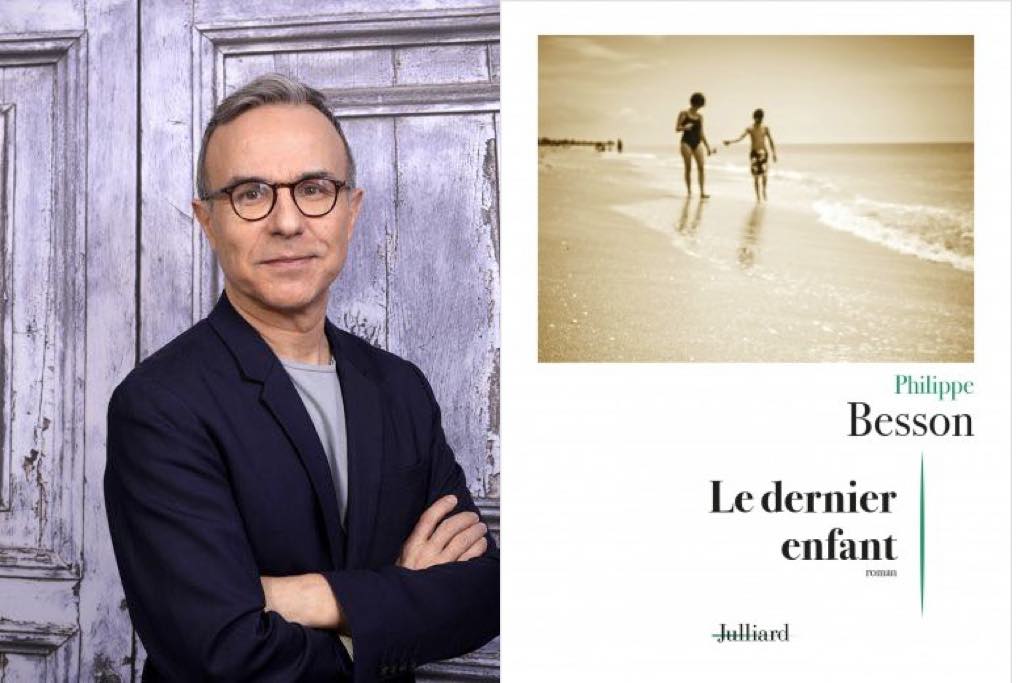

Philippe Besson’s new novel, Le Dernier Enfant, his 20th, bears many of the hallmarks of his most successful previous works. A few examples:

- His prose is concise and focuses on the inner thoughts of a few central characters.

- He chooses a subject – here the feelings of loss experienced by a mother after her last child leaves home – with which many readers will be able to relate.

- As in Arrête avec Tes Mensonges, the first book in his recent autobiographically inspired trilogy, he is not afraid to focus on ordinary family lives.

- The novel contains a scene in which a crucial conversation is held during a meal, which can be compared to the central scene in the trilogy’s final book, Dîner à Montreal.

- There is a passage in which a photograph is described in detail, as in so many of his books, perhaps most notably Un Garçon d’Italie.

- He describes events from a predominantly feminine perspective, as he did in Les Jours Fragiles with the depiction of Arthur Rimbaud’s final days as seen by the poet’s sister, Isabelle.

Why, then, is this book such a disappointment?

Perhaps the novel’s failure lies first in the fact that Besson seems to have picked an assortment of these “best bits” and produced a book that lacks the authenticity of the previous works. His decision to explore the life of an unremarkable working-class family is certainly admirable, but when these ordinary lives have nothing of real interest about them, it becomes difficult to steer clear of clichés and to maintain the reader’s attention and sympathy.

The main characters, Anne-Marie and her husband Patrick met while working for the E. Leclerc store. Thirty years later, they still have the same jobs. Patrick is gruff and silent, unable to show affection for Anne-Marie. Their third child, Théo, who is moving out of the family home to live in a studio apartment in a neighboring town, is similarly undemonstrative, displaying no enthusiasm for anything other than video games and the music of Ed Sheeran. The first sections of the novel dwell upon the most mundane details of the journey to Théo’s new accommodation, with intricate accounts of the weather, the traffic and their attempts to find a parking spot near the apartment. One can almost feel Besson straining and failing to find significance in these trivialities, and then deciding to leave them in the book anyway.

Even Anne-Marie, in her yearning for affection and reluctance to see her youngest child leave, seems like a character drawn by numbers. The attempts by Besson to give the protagonists a slightly more interesting past (her parents were killed in a traffic accident when she was young, and Théo himself had a childhood accident) are unconvincing.

As the parents return to the empty home, Besson’s narrative becomes similarly void. A section depicting Anne-Marie’s visit to her neighbor Françoise adds absolutely nothing to the story and seems little more than a space-filling exercise.

Even the ending (at which Besson is usually masterful) lurches toward melodrama. So much of the novelist’s best writing is born out of what is not said and remains unexplained: we as readers are allowed the chance to read between the lines and, in most cases, to be moved. Yet, in Le Dernier Enfant, all too often we are instructed as to how we should respond, no more so than in the final lines of the book: as Patrick is about to speak, we are informed that his words are “simples et sublimes” (simple and sublime).

Philippe Besson is a wonderful writer, to my mind one of the best current French authors. Let’s hope that Le Dernier Enfant is simply the result of a bad day at the office.

Favorite