When Guy Cogeval was campaigning for a third term as president of the Musée d’Orsay this year, one of his strongest arguments was his record as a producer of money-pulling blockbuster art shows. His reappointment this month by President François Hollande (top state museums are political patronage plums) has duly been followed by another high-octane display, “Le Douanier Rousseau: Archaic Innocence.”

Henri Rousseau (1844-1910) has caught the collective imagination as an exotic, enigmatic conjurer of enchanted forests haunted by noble savages and dream beasts – like his contemporary Paul Gauguin, a voyager returned with strange stories from distant lands. That reputation is as illusory as his art, since he never went anywhere more exotic than the Paris botanical gardens. Even his nickname, Le Douanier, pinned on him by his japing friend Alfred Jarry, is illusory, since he wasn’t a customs officer dealing with exotic imports, just a clerk in a Paris tax office.

This doesn’t fundamentally matter, since his art speaks clearly for his genius. The problem is that in the now near-mandatory curatorial trope, this exhibition has ambitions not just to showcase the art, but to build a case for the artist as a pivotal figure in cultural history – a sort of “missing link” in the evolutionary emergence of modern art. So, the show packages some 46 paintings by Rousseau in a wrapping of 54 works by earlier and later painters, presented as sources and acolytes, and a suite of densely researched explanatory curatorial texts.

The texts make the case quite persuasively – the show’s worth a visit just for those; the paintings less so.

The problem with the paintings is twofold. First, the whole transmission argument rests on a fallacy; crudely put, it goes “Carlo Cenna painted a family in a horse-drawn buggy in 1882; Rousseau painted a family in a horse-drawn buggy in 1908; Carlo Carra painted a man driving a horse-drawn buggy in 1916; so Rousseau was the link between 19th-century Romantic Primitivism and 20th-century Futurism.”

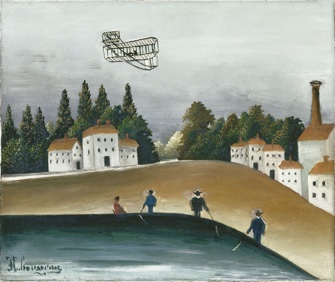

Or, “Rousseau paints a primitive airplane into a picture of guys fishing, so Rousseau is a prophet of modernism.” Reader, go see and make up your mind. This writer finds the argument less than convincing.

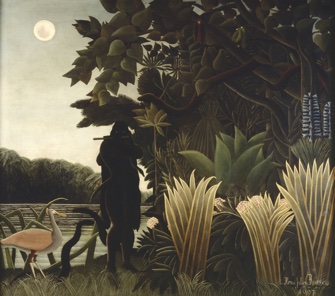

The other problem is that a lot of the paintings are, truthfully, quite mediocre. Certainly, the show includes great masterpieces – the weirdly balletic 1908 “Footballers,” a sort of four-man rugby dance set in a woodland boxing ring; the hallucinatory intensity of the jungle paintings; the mysticism of “The Dream,” painted in the year of Rousseau’s death; the dramatic intensity of the 1894 allegorical painting “War.” But these are drowned in lesser works – minor works by Rousseau; minor works by minor artists, larded with a few minor works by major artists.

A lot of these minor works are by Italian painters; nothing wrong with that per se, but it indicates a selective vision, possibly reflecting the fact that the exhibition is a joint venture with Italian backers and was shown in Venice last year.

Strangely, if these lesser works show one thing very clearly, it’s that Rousseau, a largely self-taught painter, couldn’t paint.

From a purely painterly perspective, his handling of brush and medium comes across as flat, textureless, uniform, technically inferior even to the work of the hack artists keeping him company.

And yet, none of that matters. In the end, what does come through, despite everything, is the genius of his imagination. In demonstrating his ability to channel a vision, a concept, transcending painterly representation, and his ability to simplify and concentrate form and color, the show does convincingly set him up as a true pioneer of modern artistic practice.

A blockbuster? Perhaps not. But still worth seeing.

Favorite