|

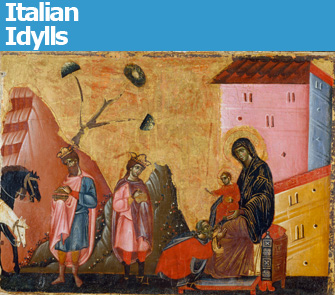

| Guido da Siena: “The Adoration of the Magi” (1270-80). © Bernd Sinterhauf, Lindenau Museum, Altenburg, 2008 |

Paris is paradise for Italophiles this spring, with two museums – the Musée du Luxembourg and the Musée Jacquemart-André – offering exquisite shows of Gothic and Renaissance Italian paintings, while the …

|

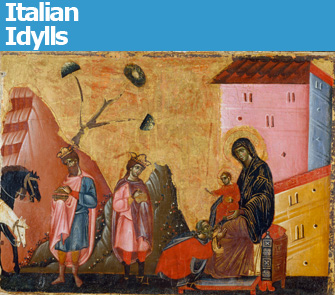

| Guido da Siena: “The Adoration of the Magi” (1270-80). © Bernd Sinterhauf, Lindenau Museum, Altenburg, 2008 |

Paris is paradise for Italophiles this spring, with two museums – the Musée du Luxembourg and the Musée Jacquemart-André – offering exquisite shows of Gothic and Renaissance Italian paintings, while the Musée d’Orsay takes visitors on a Grand Tour of the peninsula through 19th-century photographs and paintings.

“Les Primitifs Italiens” at the Musée Jacquemart-André offers a magnificent overview of the progression from Late Gothic to Renaissance painting in Italy from the late 13th to early 15th centuries, with some 50 works from the collection of Baron Bernard von Lindenau, constituted at the beginning of 19th century and only rediscovered by the Western world since the reunification of Germany. Many of the treasures in the show have been reunited with missing components of the polyptychs they once belonged to from museums like the Capodimonte in Naples and the Petit Palais in Avignon.

The first thing that strikes the eye is the brilliance and intensity of the colors in these works from the schools of Siena and Florence, followed by the charming mix of sophistication and naiveté in such early pieces as Guido da Siena’s “Adoration of the Magi” (c. 1270), with trees that seem to be sprouting flying saucers, stylized mountains and elegantly posed figures and movement. The simplicity of some of the compositions is also arresting: look at Lippo Memmi’s sumptuous “Saint Mary Magdalene” (c. 1325), a close-up portrait of the saint with her head gracefully bowed, wearing a richly colored green-lined peach robe. Memmi’s wonderful talent for drapery (and problem with painting hands, which look like claws) are also evident in a lovely “Virgin with Child” (c. 1320-22).

The touching “Byzantine” awkwardness and stiffness of many of the early works (look at the flat, rigid depiction of Saint James the Greater by Andrea Vanni, painted in the mid-14th century) gradually gives way to more naturalistic depictions of figures and the increasing use of perspective as one gem follows another. Emotion and expressiveness start to come through clearly in such paintings as Giovanni di Paolo’s “Virgin and Child” (1440-45), in which the lively Christ child looks directly at his mother and touches her face, or in the grief on the faces of the mourners over Christ’s body in the same artist’s depiction of the Crucifixion. The show ends at the moment when the Renaissance is beginning to blossom and beautifully demonstrates the gradual transition from one period to another.

It’s a shame that the Jacquemart-André’s temporary exhibition rooms are so cramped and always crowded, making it difficult to examine each work closely. Perhaps the museum should follow the example of the Musée du Luxembourg and many other Paris museums and stay open late a few nights of the week. The quality of this lovely exhibition makes the idea of a pilgrimage to the Lindenau Museum, housed in a 19th-century mansion south of Dresden, highly appealing.

|

| Filippo Lippi and Fra Diamante: “Nativity Scene with Saint Georges and Saint Vincent Ferrer” (c. 1456). © Archivio Museo Civico di Prato |

One of the last paintings in the Jacquemart-André show is Fra Filippo Lippi’s ghostly “Saint Jerome Penitant” (1435-36), providing the perfect segue into the exhibition at the Musée du Luxembourg, “Filippo et Filippino Lippi: La Renaissance à Prato,” which presents some 50 works, many of them from the Municipal Museum of Prato (currently closed for renovation), a city 15 kilometers north of its rival, Florence, which eventually came to dominate it.

After prospering in the late 14th century, Prato attracted many artists to work on its cathedral, among them Fra Filippo Lippi (1406‐69), an artistically talented friar who was also something of a roué. He fell for a beautiful young novice while painting in Prato’s Santa Margherita Convent and ran off with her. The result of their liaison was Filippino (c. 1457-1504), who also became an influential artist. Filippo escaped punishment for his misdeeds thanks to the intervention of his patron, Cosimo de’ Medici.

This show, which includes a number of works that have never or rarely been shown outside Italy, picks up where “Les Primitifs Italiens” left off, at the moment when perspective, Classical themes and more dynamic and naturalistic depictions were becoming increasingly commonplace in painting as the Gothic style faded away. The exhibition focuses on works produced in Prato by the two Lippis and some of their illustrious colleagues, including Donatello (represented by a lovely bas relief of the Virgin and Child, dating from 1415-20) and Fra Diamante (a talented disciple of Filippo who collaborated with him on many of the works shown here).

Again, the visitor is struck by the vivid, glowing colors of the paintings. Filippo Lippi was an innovator in the way he used monumental figures and fit them into the space of the canvas, while his son, who was first taught by his father and later studied under Botticelli (once his father’s student and an influence on his early work) in Florence, opened the way for the Mannerist style that developed in the 16th century with his esoteric subjects and grotesque figures. The show ends with paintings by artists who were influenced by the Lippis, among them Botticelli, Trombetto, Luca Signorelli, Zanobi Poggini and Raffaellino del Garbo.

A group of tondi, paintings in round frames that became popular among wealthy Tuscans in the late 15th and 16th century, shows how artists accommodated this new format – sometimes to amusing effect, as in Signorelli’s depiction of the Virgin and Child surrounded by four saints, all of them distorted and leaning rather awkwardly inward. A nativity scene from the studio of Botticelli accomplishes the task more successfully.

|

|

Paul Delaroche: “Pilgrims in Rome” (1842).

© Muzeum Narodowe, Poznan |

Fast-forward to the 19th century for “Voir l’Italie et Mourir” (“See Italy and Die”), at the Musée d’Orsay, which provides a glimpse of what Italy was like in the days when photography and tourism were both developing rapidly.

The exhibition sets out to show how the advent of photography in 1839 changed the world’s perception of the country during this turbulent century for Italy, which was finally unified and freed from Austrian and papal domination in 1861 after many years of struggle.

It begins with the years before the invention of photography, when painters were taking up landscape painting, with works by the likes of Camille Corot, then moves into the early years of the daguerreotype, with examples by traveling photographers like Ferdinando Artaria and, most notably, John Ruskin, who had a extensive collection of daguerreotypes.

When Pompeii and Herculaneum were discovered, photography helped spread the word about these incredible sites and brought a new wave of tourists to Italy, inspiring photographers to start creating souvenir images for them. Giorgio Sommer’s morbidly fascinating photos of the molded figures that captured the poses of Pompeians at the moment of death are included in the show.

Photography was also used to document the battles of the Risorgimento, notably those taken by Gustave Le Gray amid the ruins of Palermo in 1870. Other sections cover the documentation of archeological sites; the country’s people, captured in folkloric stereotypes in their quaint costumes; and the Pictorialist movement, which set out to elevate photography to the status of painting at the end of the century.

The latter struggle is still going on, and, to my eye, this show argues against photography’s elevation. Many of these photos are juxtaposed with more evocative drawings or paintings of the same subject, and while the photographic images are often very beautiful, most lack that transformative quality that would qualify them as art and are valuable more as historical documentation (e.g, Alinari Fratelli’s 1854 photo of Michelangelo’s statue of David in Florence wearing a fig leaf), with a few exceptions, such as Carlo Naya’s moody “Venice in the Moonlight” (c. 1875).

Be that as it may, the show is a must-see for any self-respecting Italophile.

Musée Jacquemart-André: 158, boulevard Haussmann, 75008 Paris. Métro: Saint-Augustin, Miromesnil or Saint-Philippe du Roule. RER: Charles de Gaulle-Étoile. Tel.: 01 45 62 11 59. Open daily, 10 a.m.-6 p.m. Admission: €10. Through June 21. www.culturespaces-minisite.com/primitifsitaliens/ www.musee-jacquemart-andre.com

Musée du Luxembourg: 19, rue de Vaugirard, 75006 Paris. Métro: Saint-Sulpice or Odéon. RER: Luxembourg. Tel.: 01 45 44 12 90. Reservations: www.billet-coupe-file.com. Open Monday and Friday, 10:30 a.m.-10 p.m.; Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Saturday, 10:30 a.m.-7 p.m.; Sunday and public holidays: 9:30 a.m.-7 p.m. Admission: €11. Through August 2. www.museeduluxembourg.fr

Musée d’Orsay: 1, rue de la Légion d’Honneur, 75007 Paris. Métro: Solferino. RER: Musée dOrsay. Tel.: 01 40 49 48 14. Open 9:30 a.m.-6 p.m., until 9:45 p.m. on Thursday. Closed Monday. Admission: €9.50. Through July 19. www.musee-orsay.fr/

Buy related books and films from the Paris Update store.

More reviews of current art exhibitions.

Click here to respond to this article (your response may be published on this page and is subject to editing).

© 2009 Paris Update

Favorite