|

|

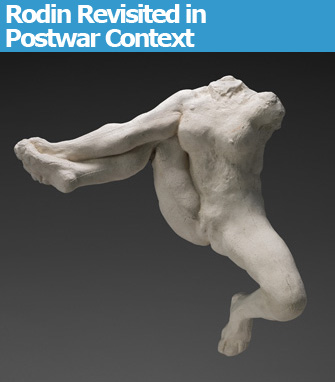

Rodin’s “Iris Messagère des Dieux” Photo: Christian Baraja. |

Since it opened its stripped-down chapel as a temporary exhibition space a few years ago, the Musée Rodin has put on a series of carefully curated exhibitions that not only …

|

|

Rodin’s “Iris Messagère des Dieux” Photo: Christian Baraja. |

Since it opened its stripped-down chapel as a temporary exhibition space a few years ago, the Musée Rodin has put on a series of carefully curated exhibitions that not only have a strong educational (but not in a boring way, so don’t let that put you off) component, but that also allow us to see Rodin’s sculptures (many of them already so very familiar) with new eyes – one exhibition, for example, asked us to consider the importance of a sculpture’s base to an artist.

The current show, “Works in Progress: Rodin and the Ambassadors,” gives us a new angle for examining the master’s sculptures by placing them in conjunction with works by postwar artists and dividing the show into categories presenting various concerns of a sculptor: modeling, smoothing and polishing, “the skin,” matter/material, combining, assembling (I had trouble distinguishing the difference between the last two categories), series and variations, reproduction, partial figures, fragments and dissolution. Who knew that a sculptor has to consider so many things when creating a new work?

Seeing a gleaming Jean Arp sculpture next to a smooth-ish Rodin piece demonstrates the importance of different types of surface, as does Rodin’s rough-surfaced “Eustache de Saint Pierre,” one of the figures in the famed “The Burghers of Calais” group, standing near Willem de Kooning’s craggy, lumpy and highly evocative “Clam Digger.”

Bruce Nauman’s monstrous “Butt to Butt” (1989), built of taxidermist’s forms put together any which way, brings up questions on how a work should be assembled. Ugo Rondinone’s airy series “Diary of Cloud” (2007-08) counterbalances the eerie sensation created by Rodin’s 26 variations on his bust of French Prime Minister Clemenceau. Jean Dubuffet’s rough papier mâché “Pince Bec” (1960) in the materials section shows how powerful simplicity can be, while three monumental aluminum sculptures by Urs Fischer in the courtyard illustrate the importance of modeling.

The reason for including each postwar piece is not always totally clear, but no matter. The show gets its point across and gives us a chance to see some of our favorite Rodin statues once again – among them the ghostly “Balzac’s Bathrobe” (just the garment without the man inside), standing near the famous felt-covered piano by Joseph Beuys and its “skin” (the piano’s former cover, removed and hanging on the wall), and Rodin’s imposing yet dynamic “Walking Man.” Some of the sculptor’s wonderful explorations of dance movements are also on show here. The overall effect of the exhibition is to remind you of what a versatile genius Rodin was.

I often complain here about the inadequacy of labels in French art exhibitions, but for once I found the texts (only on the non-Rodin pieces for some reason) not only informative, but also interesting. They were even well translated into English. Bravo!

Musée Rodin: 79, rue de Varenne, 75007 Paris. Métro: Varenne or Invalides. Tel.: 01 44 18 61 10. Open Tuesday-Sunday, 10am-5:45a. Admission: €7. Through September 4. www.musee-rodin.fr

Reader Reaction: Click here to respond to this article (your response may be published on this page and is subject to editing).

Please support Paris Update by ordering books from Paris Update’s Amazon store at no extra cost. Click on your preferred Amazon location: U.K., France, U.S.

More reviews of Paris art shows.

© 2011 Paris Update